16 Nov 2017 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

History is studded with examples of temperance movements and prohibitions, whenever alcohol was perceived as a menace to society. All of them have failed and some have wrought worse chaos in societies.

History is studded with examples of temperance movements and prohibitions, whenever alcohol was perceived as a menace to society. All of them have failed and some have wrought worse chaos in societies.

History brings two examples to mind where the cure has been worse than the disease. Czar Nicholas II, who after reading the report that the defeat of the Russo-Japanese War in 1905 was due to the drunkenness of the Russian soldiers, brought in a total prohibition on alcohol in Russia by 1914. Three years later, he was deposed by the Bolshevik Revolution.

It is said that when Czar was deposed, people ransacked the cellar in his palace for vodka. Though the prohibition was removed by the communist government in 1925, the Russians did not lose their sweet tooth (or alcohol tooth) for vodka.

Another Russian ruler attempted to wean the Russians off vodka by restricting the production and sale of vodka. That was Gorbachev, famous for Perestroika. True, the consumption dropped by 40 percent in three years but he too failed in his heroic attempt. He underwent Czar’s fate and fell from power in three years.

By 2009, the Russian males had the lowest life expectancy in Europe – only 57.6 years, the same as that of a Bangladeshi man and just one above a man in Namibia. An Oxford team of academics followed up 151,000 men for 11 years. By the 11th year, 8000 of them had died. They found that 40 percent of men die because of alcohol and that a quarter of men die before they reach the age of 55. Such is the love of vodka in Russia and its consequences.

The second prohibition was in the USA in 1920 in response to the pressure from the temperance movements led by the church. The result was the increase of crime rates by 24 percent and the emergence of Mafia, who made money by bootlegging whiskey.

The best example for a moderate response was that of England to the so-called the ‘Gin Epidemic’ in London. By 1720, gin had become so cheap that the working classes reeling with gin on London streets and alcoholism became rampant. There were succinct accounts of men and women sprawling by the roadside drunk with cheap gin. The English being English did not panic or try to bring prohibition but overcame this problem by gradually increasing the taxes on cheap gin and encouraging people to drink softer liquors. By 1770, the Gin Epidemic had left the city of London.

What can we in Sri Lanka learn from these historical facts? The first is that total prohibition of alcohol does not work and could actually bring disastrous consequences. The American prohibition of alcohol and the disastrous consequences are well known. Less known is the history of Pakistan where the Islamic Republic of Zia ul Haq banned alcohol in 1977. That, according to some Pakistani legislators, led to an epidemic of heroin abuse in the country. Today, Pakistan has half a million heroin addicts.

The second most important lesson is that once a particular alcohol beverage takes root in a given culture, eradicating that beverage becomes extremely difficult. Such beverages become the main part of rituals such as weddings, parties, after-work relaxation and now even funerals. But as the British government demonstrated, it can be done over many years with differential taxation.

Sri Lanka has much in common with the Russian vodka drinking culture. The equivalent of vodka in Sri Lanka is arrack. Vodka has 40 percent of alcohol and arrack has 32 percent of alcohol. We are both spirit drinking cultures.

The effects of such spirit drinking are striking. Apart from early death, there is an important variable that reflects the alcohol consumption of a society. That is the rate of cirrhosis in a given society. Over 60 percent of cirrhosis in a given community is related to heavy drinking of spirits and binge drinking.

Thus, Italy and France with much higher per capita drinking of wine and beer have lower rates of cirrhosis than that of Russia, where there is binge drinking of vodka. Similarly, Sri Lankan binge drinking of arrack and kasippu is the reason why it has a male cirrhosis rate of over 55 per 100,000, which is 10 times higher than that of the UK. The third similarity is that of illicit alcohol consumption in both Russia and here.

Safe drinking in terms of units of alcohol

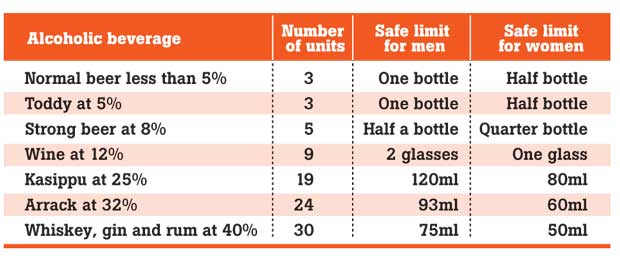

One of the most significant developments in alcohol-related research and healthcare is that of the definition of a unit. In recognition of the fact that it is the amount of alcohol that is present in an alcoholic beverage that is harmful, the UK defined an alcohol unit as that of 10 millilitres of absolute alcohol. The US followed suit defining a unit of alcohol as 12 milligrams. So did Japan and Australia with slightly differing amounts.

Today both in research and healthcare we try to ascertain the amount a person or community consumes in terms of alcohol units. Medical research has been able to clearly establish the fact that men should not consume more than three units per day and women should not consume more than two units per day. This is today called safe drinking.

Certain medical benefits such as reduction of coronary heart disease, diabetes and dementia have been attributed to such safe drinking but the medical community has not come to a definitive conclusion on such benefits.

However, even within this safe limit, two caveats exist. One is that a slight increase of risk of cancer exists, even with one drink per day, particularly for breast cancer in women. The other is that all such much publicized benefits exist only for those over 40 years. No such benefits exist for younger consumers even if they consume within safe limits. The Table provides a guide to such safe drinking.

The Table shows that despite the medical advice on safe drinking, the current pattern of drinking in Sri Lanka, like that of Russia, is far above the recommended amounts. What passes off as social drinking in both Russia and Sri Lanka is binge drinking. Binge drinking is defined as drinking five units or more on a given occasion.

It is the binge drinking that is considered a major cause of cirrhosis and mortality in alcohol abusers. Most arrack drinkers believe that drinking a quarter of arrack is safe drinking. Unfortunately, drinking a quarter bottle of arrack is still binge drinking.

Problem of illicit alcohol drinking in Sri Lanka

By 1995, it was estimated that 80 percent of alcohol consumption in Sri Lanka was that of illicit drinking.

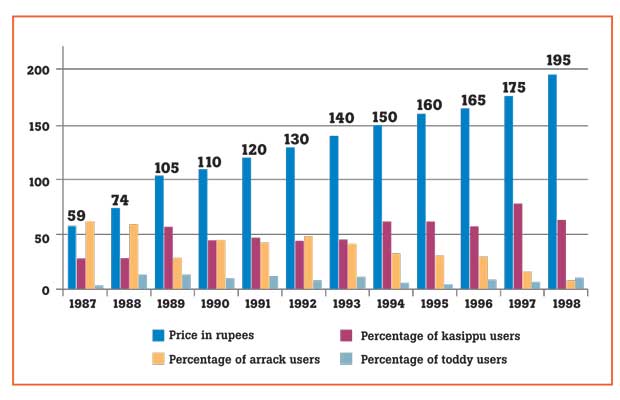

The chart shows the effects of increasing taxes on alcohol. The alcohol consumption of patients with alcohol dependence at the Peradeniya Hospital shifted from arrack to kasippu. Where 50 percent patients with alcohol dependence consumed arrack, by 1997, 80 percent of alcohol-dependent patients were using kasippu. Toddy consumption remained a marginal issue at 3 percent to 5 percent.

Next, we wanted to study the kasippu drinking culture. For this, we ventured to Thotalanga, a well-known working class area in Colombo, to conduct a study based on the principle of participatory observation. It was because a normal way of doing a survey about an illicit activity would not bring results. We stationed a research assistant, who was a sociology graduate, in Thotalanga, on the pretext that he was working in the vicinity and he collected data from the alcohol consumption while drinking kasippu with the people.

Today he is a high government official and the findings have been published as a book called ‘Illicit Alcohol’ authored by me. The study brought into focus not only the culture of drinking kasippu but the level of drinking in Thotalanga as well as the level of police corruption that was allowing kasippu into Colombo.

Our main findings were that 62 percent of the alcohol consumed was kasippu and that the cost of a unit of kasippu was Rs.3.50, whereas the cost of a unit of alcohol from gal arrack was Rs.10. The cost of a unit of alcohol was Rs.20.

We also came to a remarkable conclusion based on our study. It was that there was a thing called earning to alcohol price factor. That is the amount a person for a day is prepared to spend on alcohol. This factor was one-fifth and it held remarkably across all earning groups.

We then conducted similar studies in Ekala, Anuradhapura and Hatton. The findings were worse – kasippu was the only beverage consumed both as a social drink and for dependence. We met only a few young men who claimed to drink gin and beer. One of the youth who claimed to drink gin was actually drinking kasippu. The only exception came from some of the well-maintained tea estates in Hatton, where arrack remained the only form of drink.

The Ekala-Jaela area was a study of not only consumption but also large scale manufacturing of kasippu. Once we drove 2.5 kilometres in the Ekala area and came across funeral notices of 12 people – all of them for young men except for two elderly women. This was a chilling finding on the effects of kasippu on the health of the people in the area.

However, the common myth that it is the kasippu that is dangerous due to dangerous adulterants did not hold water in our studies. We chemically analysed 21 kasippu samples, collected from 21 areas in the country. What was most surprising was that except for one sample of kasippu, all the rest were free of dangerous adulterants. The strengths varied from 20 percent in the Kandy area to 35 percent for kasippu in the Dankotuwa area. It was not the adulterants that were killing young people but the high alcohol content in kasippu.

Public policy on alcohol

The last regime had a public policy of ‘Mathtata Thitha’ with the implication that alcohol has to be eradicated from society. However, this policy was limited to beautiful sound bites. Though no prohibition was in force, neither was there an evidence-based alcohol policy. The result of such preaching to the public to keep away from all alcohol is shown in the graph in a paper I published in a journal. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4038/sljpsyc.v2i1.3156

What the paper showed was that the actual consumption of alcohol had increased despite banning alcohol advertising and a relentless message to people not to drink. We were convinced that this was the wrong message at the time.

In order to test a different message to people, we, at the Department of Psychiatry and Australian researchers devised a unique message to a village in the Kandy area in 2010. We did not ask them to stop drinking but told them about safe drinking. We used culturally acceptable media, such as street drama and ‘JVP-style posters’, to press the message of safe drinking.

In the control village, we measured the alcohol consumption in men but did not use the same message. The results were significant beyond our expectation. The initial kasippu consumption was 50.4 percent in the study village and 52.4 percent in the control village. The follow up studies showed that alcohol consumption had decreased in the study village, including public drunkenness as well as family violence.

The most surprising finding was that kasippu consumption had completely disappeared in the study village only. Both these papers received wide acclaim and were published in the well-known journal ‘Alcohol and Alcoholism’. Our results were so striking that a major countrywide study is planned at present.

Towards a future evidence-based public policy on alcohol

We need to look at examples from history, research evidence elsewhere and our own research to formulate a public policy. Examples from the history from Russia, the USA and Pakistan clearly show that total prohibition has been an unmitigated disaster that brought more misery and complications than alcohol itself.

The second truth is that we need to be honest with the public. While drinking sundowners and Black Label at parties, we cannot ask the ordinary public to engage in ‘Mathata Thitha’. We need to take the public into our confidence and tell them the truth as we did in our community study. That may mean informing the public that toddy is a safe drink, provided it is consumed in retail amounts, as well as kasippu is a safe drink if consumed in less than 90 millilitres.

We need to inform the public that alcohol dependence is a mental disorder and that treatment is available for such people. Now specialized centres exist in Sri Lanka for the treatment of alcohol dependence. We can also learn from the example of how England controlled Gin Epidemic. By painstakingly using taxation through five successive parliamentary acts, they overcame this problem over 50 years or so. Russia was unable to control its vodka epidemic over the next 100 years. Judicious taxation has been shown to be one of the most effective forms of controlling alcohol abuse.

The major elements of such judicious taxation are two elements. One is to tax not the particular alcoholic beverage but the units of alcohol in it. For example, strong beer should be taxed more than normal beer and arrack more than wine.

The second element is not to tax the existing socially acceptable drink beyond the ordinary man’s earning. Here I would like to refer the reader to the earning to alcohol price ratio of five we discovered in Thotalanga. A reasonable man engaged in social drinking will spend only one-fifth of this daily earning on alcohol. When the legally available alcohol exceeds that ratio, that reasonable man will resort to illicit alcohol.

In order to deal with this problem, illicit alcohol should be brought into the taxation bracket. If this is not feasible or if it is only an academic’s pipe dream, the government should tax sugar heavily, which is the most important component of kasippu manufacture, as research shows.

In Ekala, there were shops that specialised selling container loads of sugar to manufacturers of kasippu. Our research assistant observed daily issues of tractor loads of sugar. Surely the government could restrict the sale of sugar to one kilogramme at a time and monitor large-scale movement of sugar.

The most important principle of taxation of alcohol, should be to make citizens think twice before buying alcoholic legal beverages and but should not too harsh to drive them into illicit forms of alcohol.

Let me end this article with the other side of the story of prohibition movements in history. Czar, who brought in prohibition abdicated and so did Gorbachev. Zia ul Haq was killed in a plane crash and the past regime that brought in ‘Maththata Thitha’ was toppled. Only the English rulers survived the Gin Epidemic despite taking over 50 years to control it.

Differential taxation will help but as in the case of Gin Epidemic, it will take over 50 years for us to see results. Meanwhile, we need to institute other measures such as nabbing drunk drivers, setting up treatment centres for alcohol dependence, public education and empowering women who are often the victims of alcohol abuse by men.

(Dr. Ranil Abeyasinghe was Head of Department of Psychiatry, Medical Faculty, University of Peradeniya. He retired in 2015. He currently serves the university as a council member)

25 Nov 2024 1 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 1 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 4 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 4 hours ago