30 Nov 2016 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The Madrid Protocol is a global mechanism for registering trademarks outside one’s home country. It reduces the time, inconvenience and cost incurred by companies that try to ensure international recognition and protection of their trademarks. In the 2016 budget, the Government of Sri Lanka allocated Rs.100 million to speed up accession to the Madrid Protocol. This was a positive response to a long-standing request made by Sri Lankan exporters. It will assist and encourage Sri Lankan exporters to invest in branding and trademarks in their market strategy and growth.

This Verité Insight shows that the path to Madrid and its benefits for Sri Lankan exporters faces a daunting pothole. That pothole exists in Colombo and is created by a very low level of trademarks registered each year despite the increase in the number of applications. It is further created by the extensive delays in processing applications by the public institution responsible for registering trademarks. A path to ‘Madrid’ is not enough – the pothole in Colombo needs a separate solution.

First: What is the benefit of trademarks?

A market economy is expected to generate price reductions and quality improvements for consumers by creating competition between produces to deliver the best value for money. For producers to compete and distinguish themselves amongst buyers their product should be uniquely recognizable; that means other producers should not be able to mimic their trademarks. Trademarks are words, images or a combination of these and act as unique identifiers. When the product of a company comes to be trusted and valued for its quality, the trademarks of the company become the repository of that value – this is how the customer recognises the historically established credibility of the product.

This competitive drive for improvement and trust among producers can only be sustained by allowing trademarks to be protected from imitation. If the benefit of a hard-earned reputation can be stolen by copying it, there will be little incentive to earn that reputation. This logic is like that of protecting the intellectual property of innovators. This is the reason for having a system of national and international registration of trademarks and providing concomitant protection. Registration normally takes place with the intellectual property (IP) offices in each country.

Second: What does Madrid Protocol achieve?

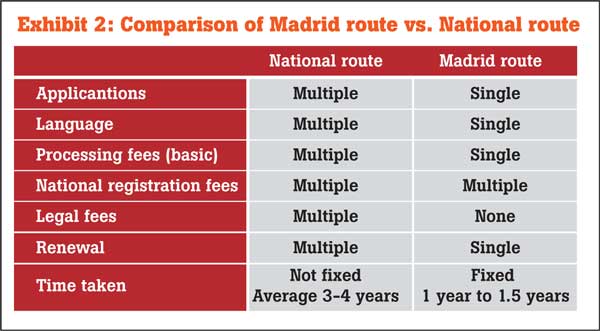

The Madrid Protocol is a centralised, global system for registering and maintaining trademarks in foreign countries. It is administered by the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO). Under the Madrid Protocol, a trademark application must first be registered at the IP office in the applicant’s home country and thereafter it is forwarded to WIPO. Thereafter, it is sent to all the countries designated by the trademark owner through WIPO (Exhibit 1).

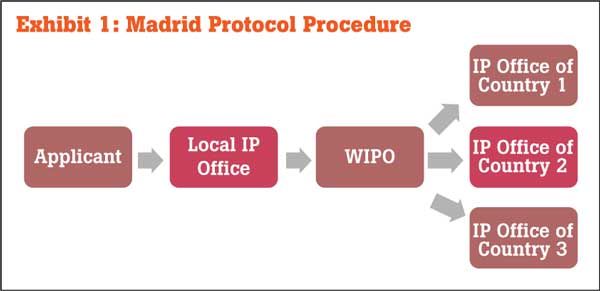

The Madrid Protocol helps to significantly reduce time by adopting a simplified process of registering in multiple countries (Exhibit 2). It ensures that the application is processed within a one to one and half-year period and reduces the cost of registering in multiple countries. Calculations made by the International Trademark Association of the United States as far back as in 2003 shows that the cost to register a trademark in the USA and 10 other countries under the national route (i.e. by applying through individual IP offices in each country) amounts to US $ 14,600 and only US $ 5,800under the Madrid route.

Third: Who is served by Sri Lanka’s accession to Madrid Protocol?

There are two constituencies that directly benefit through Sri Lanka’s accession to the Madrid Protocol. The first are international companies in Madrid member countries that are keen to supply to Sri Lanka but have not yet registered their trademark in Sri Lanka. They are helped by Sri Lanka’s accession because, then, if they lodge their application through WIPO, their application will be processed within 18 months in Sri Lanka. The second group that benefits is Sri Lankan exporters who have already registered their trademark in Sri Lanka.

Currently, Sri Lankan exporters seeking trademark registration internationally must file separate applications with the IP offices in each country of interest, after having registered in Sri Lanka. This entails multiple applications in multiple languages, in multiple countries through multiple lawyers. It is cumbersome, lengthy and costly. After accession they can immediately follow the process of lodging their application with WIPO and fast-track their trademark being registered in 113 countries that are now within the Madrid Protocol. Accession to the Madrid Protocol will enable Sri Lankan exporters to develop their product and brand with confidence, knowing that the investment in consumer confidence is duly protected. This in the longer term also encourages them to develop and sell products under their own trademarks/brand names in export markets, rather than being invisible to customers and remaining a supplier to bands/trademarks owned by others.

Problem: Pothole on path to ‘Madrid’

Research over the last few months has revealed a gaping pothole on Sri Lanka’s path to benefiting from the Madrid Protocol. The pothole is in Colombo. Accession to the Madrid Protocol requires Sri Lanka to comply with the 18-month timeframe in processing applications from other nations that come from WIPO. It has no compliance requirement on the time taken to process trademark applications from local companies. This is a concern for two reasons. First, under the Madrid Protocol, registration with the National IP office is an important first step that enables a firm to register its trademark abroad. Although lodging an application with National IP office allows a firm to lodge an international application with WIPO, if the local application gets rejected or cancelled, the international application in all designated countries also risk being rejected. Therefore, it is always better to lodge the international application after registering with the National IP office. Second, a company’s success in registering trademarks and developing a brand image at home is likely to increase the probability of success abroad. Thus, fast international access through Madrid is only useful after success in Colombo, which presently seems to be the critical obstacle for Sri Lankan firms moving to register and benefit from their trademarks.

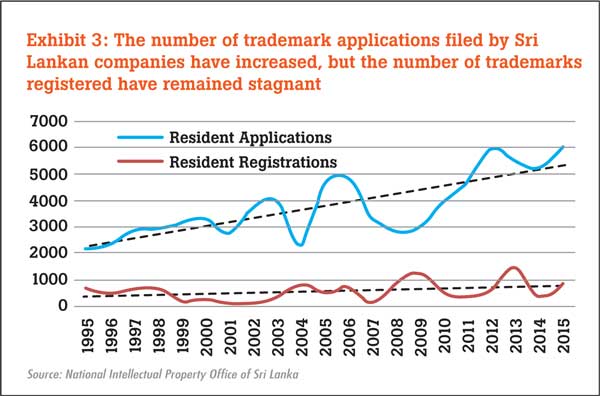

However, publicly available information reveals a large gap between the number of applications that the National Intellectual Property Office (NIPO) receives, the number of trademarks issued and the time taken to register trademarks. For example, on average, during the last decade, NIPO received 4,540 TM trademark applications a year from within Sri Lanka but only issued an average of 755 registrations per year. That is 17 percent of the average number of applications. In fact, as indicated by Exhibit 3, the number of trademark applications has increased over the years but the number registered has remained stagnant.

In contrast, the Intellectual Property office of Philippines received on average 12,949 resident trademark applications from within the country and registered 8,320 trademarks a year during the same period. That is 64 percent of the average number of applications. Vietnam received on average 22,700 resident trademark applications a year during the last decade and registered 13,053 trademarks a year during the same period. That is 57.5 percent of average applications a year.

Further, consultations with local trademark owners revealed that it can take on average 48-60 months to register a trademark in Sri Lanka. In contrast, other countries in the region process trademark applications faster: Singapore within eight to 12 months, India and Pakistan within 12+ months and Bangladesh within 18-24 months. Having to wait for 48-60 months before applying for international registration undermines the gains of Madrid accession.

The low number of registrations may be due to a much higher rate of faulty applications in Sri Lanka (compared to the Philippines). However, consultations with the private sector revealed that institutional and process inefficiencies are key reasons for the delay. The NIPO did not respond to requests for information or for meetings with senior officials despite numerous phone calls, emails and faxes. Therefore, it is not possible to provide a full analysis of the duration-data and the reasons for the very low number of trademarks registered in Colombo.

Identifying the reasons and addressing them remains vital for the country to benefit from the Madrid system. In the present context, accession to the Madrid Protocol can be like having a faster plane in the airport while travel to the airport is restricted to bullock carts.

Filling pothole by creating accountability

Like much of Sri Lanka’s bureaucracy, the NIPO is not accountable for its poor performance. However, entering an international agreement creates some level of visibility and accountability because of the automatic international monitoring, upgrading of systems and processors to be compliant with international standards and publicised feedback on compliance.

In the case of the Madrid Protocol, the obligation is to process international applications in 18 months. However, it creates no obligations to ensure a reasonable time-frame for processing registrations for local applications in Colombo. Therefore, Madrid accession is not geared to fill the pothole in Colombo. In fact, as matters stand, Madrid accession risks exacerbating the local registration problem; as NIPO is held accountable to meeting its international obligations created by the Madrid Protocol, it can neglect local applications even further. To prevent this, accountability of the Colombo Bureaucracy to Sri Lankan producers may require other instruments. At present, there is no mechanism in place for the private sector, a key stakeholder in the process, to regularly interact with the NIPO. Hence, one instrument is to put a system in place for the private sector to be an active participant in the process. In addition, another instrument could be the involvement of the oversight committees of parliament: regularly enquiring and monitoring the bureaucracy on its local trademark registration performance and status of accession to the Madrid Protocol.

(Verité Research is a private think tank that provides strategic analysis for Asia. Its main research and advisory divisions are in economics, politics, law and media. Based in Colombo, Sri Lanka, Verité Research has conducted research for the private sector, the United Nations, multilateral agencies, diplomatic missions, government departments and civil society actors. For comments and inquiries contact [email protected])

25 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 5 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 5 hours ago