03 Jan 2017 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

After a year marked by financial turbulence, political surprises, and unsteady growth in many parts of the world, the Fed’s decision this month to raise interest rates for just the second time in a decade is a healthy symptom that the recovery of the world’s largest economy is on track.

After a year marked by financial turbulence, political surprises, and unsteady growth in many parts of the world, the Fed’s decision this month to raise interest rates for just the second time in a decade is a healthy symptom that the recovery of the world’s largest economy is on track.

The Fed’s action was hardly a surprise— markets had for weeks placed a high probability on last week’s move. But market developments preceding the Fed decision did surprise many market watchers.

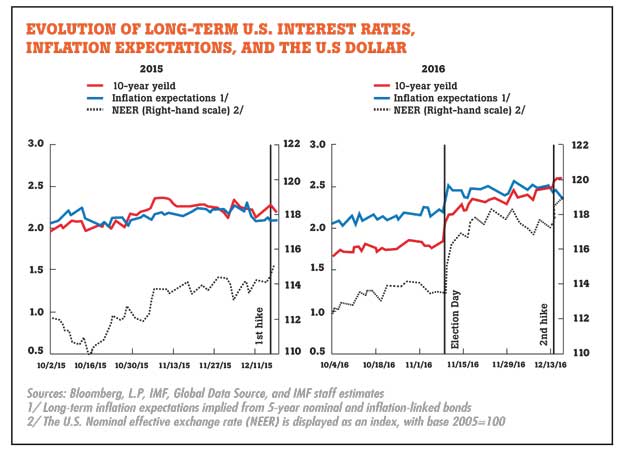

Especially striking were the sharp upward moves in longer-term U.S. interest rates, the dollar, and market-based measures of long-term inflation expectations soon after the U.S. presidential and congressional elections of November 8. No comparably abrupt market reactions preceded the Fed’s previous interest rate hike of December 2015 (see chart).

The dollar has risen further in the days following the Fed’s recent move.

Time will tell if these market developments point to a new trend. Most likely, however, the election marks a shift in the U.S. policy regime with potentially even bigger future effects on prices and activity—abroad, as well as in the United States. Spillovers outside the United States will be felt especially strongly in emerging market economies, where for some, the advantages of enhanced competitiveness due to weaker currencies may be finely balanced against vulnerabilities.

Something has changed

From the start of 2016 and through the U.S. election, Treasury yields had been particularly low. Discussion of the global outlook, including at the IMF, stressed the risks of protracted low growth and continuing deflation pressures—even secular stagnation, with persistently low interest rates.

Longer-term nominal interest rates are, however, strongly influenced by expectations of the future path of the Fed’s policy rate, which in turn responds to U.S. inflation pressures and the economy’s underlying strength. Thus, the sharp post-election turnaround in longer-term U.S. interest rates changed the conversation: it likely reflected not the looming December rate hike alone, which was already widely anticipated, but also a shift in expectations about the future interest rate path and future demand in the U.S. economy. Consistent with those expectations, while last week’s interest-rate hike was itself not unexpected, the future path of interest rates that Federal Open Market Committee members anticipate also steepened, and now suggests three interest rate hikes in each of the next two years. The timing of the abrupt asset-price movements—coming within days of the U.S. election—is the key clue about what moved markets. The election of Donald Trump as president, coupled with continuing Republican control of the Congress, ended six years of divided U.S. government.

Implications for the future

Republicans in Congress have long advocated lower personal and corporate tax rates. President-elect Trump campaigned on a platform that included not only substantial tax cuts, but also increases in some categories of government spending, notably defense and infrastructure.

At this early stage, it is hard to know precisely how the shift in fiscal policy will look. One thing seems clear, however: it will turn more expansionary through some combination of more spending and lower tax rates.

In general, any increase in U.S. aggregate demand will generate some rise in real output—as new workers are hired, others work longer hours, and machinery is used more intensively—and some upward pressure on inflation. With the overall unemployment rate at 4.6 percent and other measures of labor market distress largely recovered from the financial crisis eight years ago, there could be little remaining slack in the U.S. economy. Unless labour force participation and overtime work rise significantly, there is a chance that inflation pressure therefore rises noticeably. This seems to be what the Fed has in mind when it predicts it will raise the federal funds rate more quickly. More rapidly rising U.S. interest rates signal further dollar appreciation. Tax incentives for U.S. corporation to repatriate their past profits held abroad, which some estimate at US$ 2.5 trillion, could also push the dollar up. Given faster demand growth, the outcome will be a widening U.S. current account deficit that is, more borrowing from abroad. Some of it will possibly finance a growing Federal fiscal deficit, depending on the precise features of the U.S. fiscal package, the extent to which it is paid for by budget cuts elsewhere, the path of government borrowing rates, and the economy’s growth response. The U.S. growth will respond more strongly, with lower inflation, if any infrastructure spending is carefully designed to boost potential output, while tax measures encourage investment, labour supply, and inclusion.

International challenges ahead

Given the United States’ central role in the world economy, big changes in its policy mix have first-order effects beyond its borders. Advanced economies with currencies that depreciate against the dollar will benefit both from higher U.S. growth and from more competitive exchange rates. For most of these economies, currently struggling with below-target inflation, any resulting inflationary pressure would (at least initially) be welcome. They may also see upward pressure on interest rates, posing a fiscal challenge for countries that are highly indebted but do not benefit enough from the positive demand spillovers that are driving their interest rates upward. Emerging market economies can also benefit from more competitive currencies and higher U.S. demand. But although many emerging market economies have increased their policy buffers (e.g., foreign reserves), reduced currency mismatches, and improved financial oversight frameworks, some could still feel stress, especially where there are pre-existing political or economic strains. Historically, U.S. interest rates have been one of the key drivers of net capital flows into emerging market economies. Flexible exchange rates can be helpful as a buffer against rapid outflows, as they allow international portfolios to rebalance through currency changes rather than reserve losses. A combination of rising dollar interest rates and domestic currency depreciation could reduce liquidity or worsen balance sheets, however, especially given the importance of dollar borrowing by residents and non-resident corporates in emerging market economies. Furthermore, currency depreciation might spark higher inflation. Policymakers in emerging markets therefore will remain vigilant.

If sharp exchange rate shifts and growing global imbalances follow the U.S. policy regime change, protectionist pressures become a major risk, as in past similar circumstances. Given the desire of advanced economy governments to maintain manufacturing, where emerging markets have made big inroads in recent decades, it is most likely that emerging market economies are the main targets for higher trade barriers erected by advanced economies.Governments should therefore keep in mind that protection is likely to be counter-productive at home—even before trade partners retaliate, as they will be tempted to do. The integration of advanced economies into truly global supply chains underscores this danger. In an environment of sharply divergent policy mixes, as we may now be facing, the rules of the global trading system will be more important than ever.

(Maurice Obstfeld is the Economic Counsellor and Director of Research at the International Monetary Fund)

09 Jan 2025 3 hours ago

09 Jan 2025 5 hours ago

09 Jan 2025 7 hours ago

09 Jan 2025 8 hours ago

09 Jan 2025 8 hours ago