05 Oct 2017 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Bamboo is a well-established cultural feature of many regions throughout the world. Its diversity and versatility are well-documented – some 1250 species and 1500 traditional applications have been identified. Notably, the main users are the rural poor and perhaps for this reason, it has largely been taken for granted by the wider community. As such, bamboo has not received the mainstream recognition it deserves as a material resource.

Bamboo is a well-established cultural feature of many regions throughout the world. Its diversity and versatility are well-documented – some 1250 species and 1500 traditional applications have been identified. Notably, the main users are the rural poor and perhaps for this reason, it has largely been taken for granted by the wider community. As such, bamboo has not received the mainstream recognition it deserves as a material resource.

Bamboo is the fastest growing woody plant on the planet but it actually belongs to the grass family. Most species produce mature fibre in about three years, much faster than any tree species. Some species grow up to one metre a day, with the majority reaching a height of 30 metres or more.

Bamboo can be grown quickly and easily and harvested sustainably on three to five-year rotation. Bamboo is a truly renewable material.

The bulk of bamboo is gathered from the wild or rural environment. However, in many areas bamboo resources have dwindled due to overexploitation and poor management and this issue needs to be addressed through well-organised and managed cultivation if bamboo utilisation is to develop on a sustainable basis. Plantations are already being raised in China and India to support the pulp and paper industry.

Plantation technology for large-scale cultivation of bamboo is known – standard practices have been developed with culm cuttings and tissue culture is gaining acceptance. National afforestation programmes can therefore be implemented to meet the future demand.

Furthermore, improved technologies for raising plantations of bamboo in degraded areas, on logged over forest and in agro-forestry initiatives can be achieved through further research into biodiversity, species selection and genetic improvement.

The key question is how can bamboo contribute to sustainable development? Overall, the goal is to utilise bamboo resources for economic growth, employment generation and livelihood creation and not least, environmental protection.

Bamboo has exemplary ‘green’ credentials. It can help reduce the demand for wood from natural forests and contribute to improvements in the built environment. It is adaptable to most climatic conditions and soil types, acting as an effective carbon sink and helping to counter the greenhouse effect. It is finding increasing use in land stabilisation, to check erosion and conserve soil. It can be grown quickly and easily – even on degraded land and harvested sustainably. Bamboo is a truly renewable, environmentally friendly material.

The use of bamboo for local production of currently out-sourced or imported high-value products is an important first step to retaining cash in the local economy. Asset creation and local consumption will be boosted by increased circulation of money within the local economy and most of this can be achieved utilising local people and materials.

The solution to employment generation and livelihood creation lies in creating partnerships between the community and industry. Value addition will begin at community level with activities such as cultivation, harvesting, preservation, processing and transportation. Backward integration of bamboo into production and processing will require significant labour input, with improved opportunities for women in view of ease of handling, traditional skill requirements and greater time flexibility.

The success for bamboo in the industry depends on a sustainable supply. Livelihood opportunities will exist in cultivation – for home use, local sales or supply to industrial processors. Bamboo can provide a cost-effective short-term return – community agroforestry and cultivation on marginal land will bring benefits to the rural poor.

Utilisation at local level will present an array of livelihood opportunities. These can be in traditional areas, such as handicrafts and furniture, produced in finished form or supplied as components to small and medium enterprises (SMEs) for further processing (e.g. mats for bamboo matboard).

‘New’ technologies can also be exploited – for example, the supply of building components – from primary processing through treatment to prefabrication and the supply of ‘kit’ houses.

The increasing industrial role for bamboo will provide jobs and income for the poor. High value-added products requiring an industrial base include roofing sheets, plywood and particleboard, laminated components (for construction, joinery and furniture), high-quality flooring and pulp and paper.

Other opportunities for community-industry partnerships will include the use of bamboo for reinforced roads, pedestrian bridges, culverts, retaining walls, dams, water tanks, fuelwood, briquettes, charcoal, food and food storage bins.

Therefore, taking into account all that bamboo has to offer, it is well-placed to address four major global challenges:

Livelihood security, through generation of employment in planting, primary and secondary processing, construction, furniture and the manufacture of high value-added products

Ecological security by conservation of natural forests through substitution of primary timber species, as an efficient carbon sink and as an alternative to non-biodegradable and high embodied energy materials such as plastics and metals

Sustainable food security through agro-forestry systems, by maintaining the fertility of adjoining agricultural lands, control of erosion and in the case of bamboo, as a direct food source

Shelter security, through the provision of safe, secure, durable, affordable housing and community buildings

The challenge is how to bring this knowledge to the attention of the broadest possible audience – from policymakers to artisans and mobilise the resources necessary to deliver the benefits to the poorest members of society. The current low-profile of bamboo development and the weakness of the global bamboo market can be attributed in large part to the restrictions of the supply and demand cycle.

The market cannot exist without products, products cannot be manufactured without raw material, raw material cannot be produced without investment in plantations and investment is unlikely without a market. A coordinated programme of interventions by government, industry and community is required to break this cycle and achieve the goal of sustainable bamboo development. The principal areas to be addressed are supply, standardisation, research and extension, training, fiscal policy, demonstration and quality.

Sustainable supply

A policy of organised planting, careful management of plantations and natural stands, appropriate regulation of supply and improvements in the supply chain are prerequisites to any other interventions aimed at promoting bamboo as a building material.

Standardisation

The lack of guidance on the use of bamboo as a material and product has been a major obstacle to its wider adoption. A recently drafted international standard on construction marks a first step to addressing this problem and new or amended national regulatory instruments such as manuals, codes of practice, specifications, building regulations and standards are now required.

Research and extension activities

The will must exist at government level to explore the potential of alternative materials and to put in place the resources and mechanisms to carry out the necessary material developments and evaluations. Where this capacity already exists, it is often necessary to reorient the approach of research institutions to link them directly with the building industry, together with their government and private sector clients.

Training

Curriculum revision is required to give greater emphasis to the new technologies. This would apply to institutions training high-level artisans or technicians for the construction industry, as well as professionals such as architects, building technologists, civil, structural and mechanical engineers and quantity surveyors.

Fiscal policy

Financial incentives are required to encourage the establishment and support of industries involved with the new technologies. Micro-credit and self-help schemes for community-based activity should also be supported. In addition, the widespread policy, which limits the advance of bank loans and mortgage on ‘bamboo’ houses, must be reviewed.

Demonstration and quality

Effective dissemination aimed at popularising new products and technologies is vital considering the negative perceptions held by many about bamboo. Even when issues of durability and strength are resolved, the question of acceptability remains. In this regard the quality must be of the highest level achievable, since any shortcomings in the standard of manufacture, detailing and finish will be reflected, unfairly, on the material as a whole. While demonstration typically takes the form of permanent exhibits (e.g. technology information centres), the possible use of travelling exhibitions, fairs and festivals, websites, newsletters and television should not be overlooked.

Bamboo in construction

One billion people live in bamboo houses worldwide. For the most part, they are low grade, impermanent buildings, which belies the material properties of bamboo and does little to promote its image as a viable construction material. At little extra cost, these buildings can be upgraded to provide safe, secure and durable shelter, benefiting the most vulnerable members of society.

Perhaps the major factor contributing to the view of bamboo as a temporary material is its lack of natural durability. Bamboo is susceptible to attack by insects and fungi and its service life may be as low as one year when in ground contact. However, the durability of bamboo can be greatly enhanced by appropriate specification and design and by the careful use of safe and environmentally friendly preservatives such as boron.

The main structural advantages of bamboo – its strength and light weight – mean that properly constructed bamboo buildings are inherently resistant to wind and earthquake forces. These properties can be effectively exploited through careful yet simple design and detailing.

Even when issues of durability and strength are resolved, the question of acceptability remains. A bamboo building need not look ‘low-cost’, nor need it necessarily look like bamboo! Imaginative design and the use of other locally available materials within the cultural context can make the building desirable rather than just acceptable.

Bamboo – International view

Bamboo has a long history as a building material. It is widely used in construction throughout the world’s tropical and sub-tropical regions, with a range of applications to match or even exceed those of timber. In Central and South America, bamboo buildings of every description can be found – from low-grade temporary shanties to exclusive, architect designed mansions.

Bamboo products for use in construction are increasing in availability. These range from bamboo matboards (flat and corrugated), through more sophisticated panel products such as fibreboard, ‘plyboo’ and flooring, to large laminated sections (currently under development) for use in external joinery.

Bamboo use is not restricted to building. Bamboo has been used as concrete reinforcement and development work is continuing in this field. Bamboo is used for light traffic bridges and the feasibility of constructing large span bridges carrying vehicular traffic has recently been demonstrated in Colombia. Bamboo as scaffolding is well known (40 storey construction is not uncommon in the Far East) and its use is set to increase as a result of the development of a design and erection guide in Hong Kong.

Other construction applications include ground stabilisation, through the use of retaining walls and piling and coastal protection (recently trialled in Sri Lanka).

Bamboo – Our experience

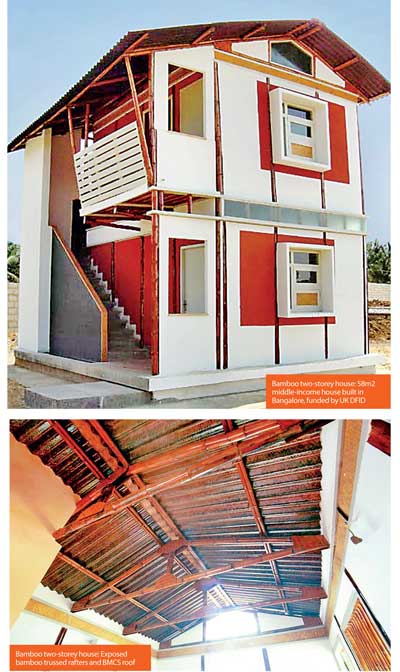

We have recently completed a project in India to develop and promote a cost-effective bamboo-based building system. The project is designed to provide safe, secure and durable shelter at a cost that is within reach of even the poorest communities in developing countries.

The project has demonstrated that with careful specification, detailing and environmentally friendly preservation, the life of bamboo can be extended to match that of other building materials. Prototype testing has been employed to provide an effective and visual demonstration of the performance and strength of components and assemblies and the resistance of walls and roofs to wind, impact and earthquake forces.

During the first phase, a building system was developed based around an integrated, resilient bamboo skeleton. Wire ties, bolts and straps ensure the entire framework is positively connected to become a single, composite unit. When cement mortar is applied to the walls, they become very strong but still retain their lightness and resilience. These characteristics make the construction inherently resistant to earthquake forces.

The bamboo building system is sustainable and cost-effective. It is also simple to erect, strong and durable. As such, it incorporates all the essential requirements for affordable shelter. Moreover, the basic system can be enhanced through improved use of shape, space and colour at little or no extra cost. Overall, the system effectively demonstrates that desirability and quality are fully compatible with affordability.

For the second phase, the technology was applied in the development of two-storey construction and designs for larger community buildings such as schools and health clinics. In addition, the use of bamboo for the construction of footbridges in rural areas has also been investigated.

In the demonstration buildings, the emphasis was shifted to showcasing the technology in a manner that would highlight its architectural and aesthetic appeal but without increasing cost. In effect, the aim was to show that an affordable building need not look low-cost but rather that it can be attractive and desirable.

Up to this point, construction had been restricted to single-storey buildings. It was now time to build on the success of the earlier work, expanding the scope to include two-storey construction, while retaining the design philosophy and key features of the original system.

In order to keep the design as simple as possible and minimise construction costs, a rectangular layout was adopted. A team of architects was briefed with taking the basic plan and enhancing it through improved use of space, shape and colour.

The new challenges presented by two-storey construction – particularly the suspended first floor and increased column loads – were addressed in large part by creative design and small-scale prototyping. A series of load tests on structural elements provided invaluable information on likely performance and led to innovative solutions for the first floor structure and ground floor columns.

A platform frame approach similar to that for timber-frame construction was adopted. This limits column lengths to practical sizes and provides for more straightforward placement of the first floor beams.

The resulting design features a series of new developments, including:

Built-up columns – double culms connected at intervals by bolted matboard inserts and supported on tubular steel shoes

Double-skin walling – single bamboo columns with plastered bamboo grid on both sides, giving the appearance of a solid masonry wall

Composite floor beams – round bamboo flanges and a lightweight folded steel web spanning 3.6m

Lightweight composite flooring – 35mm bamboos at 150mm centres supporting a matboard deck with a cement-cinder screed, spanning 1.2m

During the construction process, the two-storey system evolved considerably beyond the design and prototype stage with onsite inputs from designers and craftsmen providing solutions to a number of practical problems, which either could not be addressed by the design process or had not been anticipated.

The flexibility of the building method allowed for some interesting additions and enhancements. In particular, a clerestory was incorporated at first-floor level, creating the appearance of a ‘floating’ upper storey and increasing the amount of light entering the ground floor. Double-skin walling offered an interesting architectural contrast to the single skin (exposed column) method and was used in the bathroom and kitchen areas to provide full protection to the bamboo against wetting. The finished building features a covered external staircase to maximise useable floor space, a verandah and balcony with extended roof overhang. Other features include a kitchen at ground floor, internal toilet and shower on both floors and integrated plumbing and electrical wiring.

The two-storey house represents a major advance in bamboo construction technology, while still remaining simple and affordable. It incorporates many new developments, showcasing the bamboo building technology in a dramatic and unexpected way to further dispel preconceptions of bamboo as a temporary and undesirable material. The building, which is both accessible and highly visible, reflects an increasing awareness among young professionals in the developing world of the need for appropriate and sustainable building methods and materials.

(Lionel Jayanetti is a former consultant to Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations)

06 Jan 2025 1 hours ago

06 Jan 2025 2 hours ago

06 Jan 2025 2 hours ago

06 Jan 2025 2 hours ago

06 Jan 2025 2 hours ago