14 Jul 2016 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) issues are  a major consideration for companies engaged in international trade of agricultural produce.

a major consideration for companies engaged in international trade of agricultural produce.

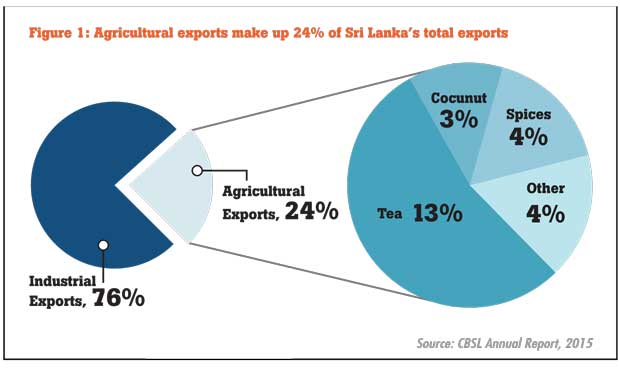

Agricultural exports (tea, spices, coconut, etc.) account for almost one-fourth of Sri Lanka’s total exports (Figure 1), providing an important source of foreign exchange and livelihoods for people in the country. However, earnings from agricultural exports experienced a notable decline in 2015, falling by 11.2 percent to US$ 2,481 million. With the spotlight on exports to drive growth, more needs to be done to support the industry.

There are a slew of international and national – public and private - standards for every food product relating to animal plant health and food safety. The interactions between Sri Lanka’s regulatory bodies and the private sector can play a crucial role in facilitating the compliance process. Staying informed of the latest developments and implementing processes to efficiently comply, are necessary to remain competitive against other exporters and import-country domestic producers.

SPS gaining prominence

As tariff barriers fall, SPS measures are gaining prominence as one of the main sticking pointsfor trade flows. Particularly, developing countries are concerned that their exports to richer countries are hampered by unnecessary new measures.

The World Trade Organisation (WTO) gives countries the freedom to set their own standards as long as these conform to the minimum international guidelines. However, there is a fine balance to strike between safeguarding the welfare of domestic consumers whilst avoiding unnecessary regulations that ultimately result in protectionism – unfairly benefiting domestic producers.

Tackling evolving standards

Given the raft of standards and revisions that take place regularly, the dissemination of this information is vital. The Sri Lankan Standards Institute (SLSI) is the designated national standards body in Sri Lanka and is the primary point of contact with the International Organization for Standardization. Exporters, however generally reach out to their respective industry regulatory bodies such as the Sri Lanka Tea Board (SLTB) to keep up-to-date with new standards. When problems arise in relation to new standards implemented by specific countries, the result can be a dramatic decrease in market share for Sri Lankan companies in those markets.

There are some countries that opt to implement their own standards and testing/certification schemes despite the existence of equivalent international ones. This often requires respective country officials to undertake factory visits and issue certification following inspection. This is a cumbersome process and requires renewal, which is prone to delays and further issues. This was experienced by Sri Lankan tea companies exporting to some African and Middle Eastern countries. Some exporters complain that the difficulty in meeting individual country standards resulted in a diminished market share.

Another instance of this was in Iraq where new standards set the yeast and mould count for tea at 100ppm compared to 1000ppm recommended in the ISO guidelines. These stricter rules are prohibitive for tropical countries such as Sri Lanka where moisture levels are naturally higher. Similarly, Iran introduced a limit on copper of 6.5ppm, which was far more stringent than the 100ppm international standard.

There is an escalation process by which these matters get resolved. The first is through the two trading companies themselves, whereby companies ask assistance of their counterparts in the importing country. Once this avenue is exhausted and the issue persists, the industry regulatory body can get involved on the company’s behalf. There was an example of this in the tea industry where the SLTB intervened on behalf of Sri Lankan tea exporters. The case related to rare earth testing in China where there were concerns that the measures were having the effect of a non-tariff barrier rather than implementing necessary safety standards. To resolve the issue, the SLTB visited China to discuss the matter with the Chinese authorities and find out more about the tests and their limits.When this does not yield results and there is evidence that exporters are being unfairly disadvantaged, the matter can be taken to the WTO SPS Committee. In 2005 and early 2006, Sri Lanka raised a specific trade concern in the SPS Committee about the European Union’s import restrictions on cinnamon exports from Sri Lanka. The issue related to Sri Lanka’s practices of burning sulphur as a way of protecting cinnamon from possible fungi and insects. This traditional practice left some sulphur residue. Through the SPS Committee, Sri Lanka was able to clarify that the residue levels were not in breach of the international standard and reported soon after that the issue had been satisfactorily resolved.

Information asymmetries and institutional capacity constraints

However, these instances of successful resolution are in the minority. Problems still arise in two forms - (1) the presence of information asymmetries and resulting uncertainty over what compliance requires and (2) limited capacity in Sri Lanka’s regulatory bodies/testing facilities/inspection procedures that limit the ability of local exporters to compete abroad.

The lack of standards harmonization between countries and the sheer breadth of coverage of the standards makes staying current with developments a challenge for exporters. Furthermore, confusion often arises where standards are unclear on their product coverage resulting in buyers purchasing conservatively and avoiding otherwise good suppliers.

Where standards are known, exporters are often hindered by inefficient domestic processes or lack of facilities in the country. Companies complained of lack of coordination between the relevant governmentagencies responsible for SPS issues.Moreover, companies report difficult relationships with the regulator. In many cases, testing requirements are such that it is more cost effective to send samples abroad for testing rather than carry them out locally.

The regulatory and standards bodies also have limited capacity. Exporters point to several instances of delays in certificate issuance and testing as agencies cannot handle large numbers. Furthermore, many processes for export approvals are still manual, held back by systems in place at regulatory bodies.

Seeking solutions

Further work should be done by regulatory authorities to facilitate knowledge sharing and engender trust with the exporters. Internal inefficiencies need to be addressed urgently; documents should be processed in electronic formats and agencies should be able to work together where multiple departments are required for the certification process.

Investment is also required in domestic testing. Capacity of the SLSI and other authorized laboratories needs to be raised to improve the efficiency of existing services and recognition of Sri Lankan tests and certificates in importing countries. Sri Lanka should seek to negotiate Mutual Recognition Agreements on standards, testing and certification under its existing trade agreements. Technical support from the main trading countries would also be helpful to ensure that the country meets the standards required in such markets.

Life would be simpler if every country adopted the ISO standards. However, the likelihood is that countries will continue to diverge in their expectations, aided by increasingly savvy consumer groups in markets abroad. The difficulty for Sri Lankan exporters will be keeping up to date with these trends, particularly in markets which are already very stringent, such as the EU. The way forward for Sri Lanka is to be proactive in setting standards rather than be “standard-takers”, particularly in products where Sri Lanka is the largest producer/exporter.

(Chantal Sirisena is a Research Assistant at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS))

10 Jan 2025 2 hours ago

10 Jan 2025 2 hours ago

10 Jan 2025 3 hours ago

10 Jan 2025 3 hours ago

10 Jan 2025 4 hours ago