08 Sep 2016 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

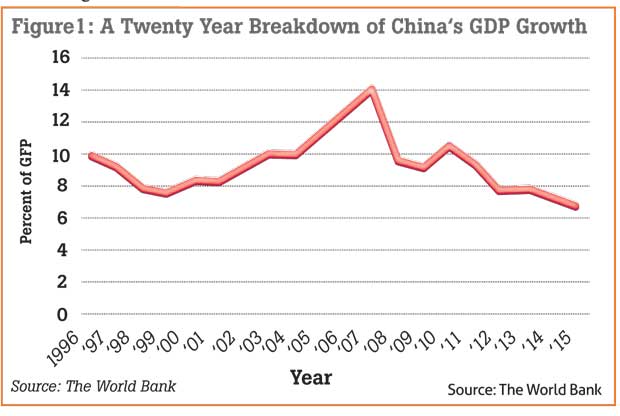

China’s rapid development has been well documented. Since the initiation of market reforms in 1978, China’s GDP growth has averaged 10% per annum; an unparalleled feat amongst developing nations. Such brisk growth rates have been instrumental in developing large swathes of the nation and in lifting a significant portion of the population from poverty.

However, growth rates have dipped over the last few years – between 2012 and 2015, the Chinese economy grew at an average of 7.4 percent per annum. Whilst this plunge corresponded to a global downturn, some argue that China’s languid growth rates paint a deeper picture, one that shows an economy overheating amidst supply side inadequacies.

Chinese authorities have dismissed such claims, but do agree that if necessary policy reforms are not executed in the next few years, the nation would find itself facing the middle-income trap.This concern has been echoed by Finance Minister Lou Jiwei who noted in 2015 that there was a 50 percent chance of China sliding into the Middle Income Trap in the next five to ten years.

The middle income trap:

implications for China

The Middle-Income Trap is often generalized as a developmental trap, a predicament associated with diminishing rates of productivity in economies that havebeen experiencing rapid growth.

China’s rapid growth was spurred by the manufacturing sector, as firmsutilized the low wage structure to produce goods that were price competitive in the global market. The strategy has borne sizeable dividends – China has been successful in alleviating more than 800 million citizens above the poverty threshold.

However, such successes now act as an impediment to the continuous use of a similar strategy. China’s burgeoning middle class has now caused a wage spiral that has reduced the comparative advantage of manufacturing in China. Firms are incentivized to invest in Bangladesh, Thailand, Indonesia and Mexico (rather than China) as their labour costs are considerably lower. This predicament is further exacerbated when one examines the gap in productivity and innovation between China and high income nations. Lapses in such fields act as a hindrance in development endeavours; it creates a scenario wherein China lacks the resources to integrate into the higher end of the value added market.

Thus, this condition – especially in regard to China – has been identified as a “sandwich trap”, where the country is trapped between cheap labor competition from below, and exclusion from higher value-added markets from above.

It is in this conjuncture that China has unveiled its 13th Five Year Plan. This broad, ambitious proposal aims to double China’s income per capita by 2020, compared to 2010 levels. In other words, the plan envisions a development trajectory not hindered by slowdowns vis-à-vis Middle Income Trap.

The 13th five year: future scope for development

China’s development policies are closely aligned to its socialist roots; reforms are orchestrated as per the “five year plans” proposed by the Central Committee (CC) of the Communist Party of China (CPC).

The five-year plans are thus important precursors for growth as they delineate the policy reforms and development endeavors that would be implemented in the medium to long term. In such a scenario, the recently ratified (by the National People’s Congress) “13th Five Year Plan” becomes even more important.

The 13th Five Year Plan is molded upon Secretary General Xi Jinping’s call for China to adapt to a “New Normal”. Under this concept, China’s development objectives will shift from expanding ‘product volume’ and ‘capacity’ to upgrading ‘product quality’ and ‘production innovation’. Furthermore, the new plan calls for a shift from high speed to medium-to-high speed growth. Growth will therefore be maintained at around the 6-6.5 percent mark, a shift from the target of 7.5 percent set by previous plans. The 13th Five Year Plan, being a document comprising 20 sections and 80 chapters, details several areas of focus. Some examples are:

3Supply Side Reform: Over the next decade, the State will deepen the reform initiatives in regard to State Owned Enterprises, reorient public capital flow and reevaluate the existence of certain monopoly industries. Furthermore, tax reforms will be initiated and incentives for private entrepreneurship will be strengthened. China’s primary goal in undertaking such large scale endeavors is to absorb excessive production and phase out excessive production capacity. Such reform is essential to fulfill China’s ambition of realigning its economy as a quality-oriented and innovation hub.

3Innovative Development: This is a prerequisite for any potential foray into the high value market. While China is the second largest contributor to global R&D investment, the per capita breakdown is far from ideal. The 13th Five Year Plan aims to create a domestic field more conducive for investments in innovation. The state will provide incentives for indigenous innovation and in addition, will procure international patents where necessary to ensure that innovative practices are not hindered.

3Regional Development: Domestically, the state intends to continue its policy of integrated development especially between the Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei Districts and Municipalities. Furthermore, plans to create a ‘Yangzte River Economic Belt’ will be commenced. On an international scale, China will continue to support the ‘One Belt One Road’ initiative to promote cooperation between Asian nations.

3Open Development: Under the new Five Year Plan, China will continue to invest in ‘Special Economic Zones’ as a meanstopromote international production capacity,global trade and investment.

Opportunities for Sri Lanka

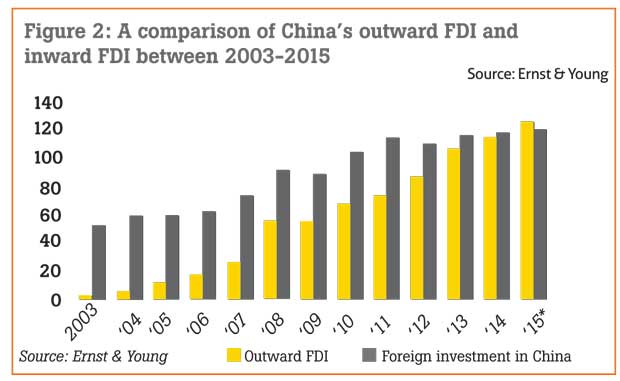

China’s efforts to limit its excess production capacity under the new plan will create a window of opportunity for developing nations to obtain vital Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). The close ties between Sri Lanka and China, coupled with the island nation’s proximity to international trade routes, make it an ideal destination for investments being reallocated.

The close diplomatic ties provide scope for bilateral ventures that accelerate the transfer of capacity to Sri Lanka. Sino-Lankan cooperation is already evident in this field – high level negotiations are already under way to a construct a “Special Investment Zone in Hambantota”. China has shown interest in partnering with the government in developing special economic zones in other regions of the island as well. In a recent trade discussion, the Chinese Ambassador to Sri Lanka, H.E Yi Xianliang, has stated that his nation is prepared “to commit over $5 billion in FDI over the medium to long term for special economic zones”.

Such investments will helpimprove thelabour force by creating employment opportunities and will provide an impetus to maximize productivity potential. Furthermore, the creation of similar manufacturing enclaves will set an ideal foundation for Sri Lanka to integrate into global supply chains in the future.

The regional focus of the 13th Five Year Plan is inextricably linked with China’s One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative. Sri Lanka, being a strategic partner of the ‘Maritime Silk Road’, has the potential to position itself as an Asian growth hub in the heart of the Indian Ocean.

For instance, Sri Lanka can analyze China’s success story in positioning Shanghai as a centre for international trade and investment. Using Shanghai’s experiences as a base, Colombo (coincidentally a sister city of Shanghai) can perhaps be revamped as a Special Economic Zone catering towards the Indian subcontinent.

However, it is pertinent to note that foreign investment is no panacea for development. Authorities have to ensure that the inward foreign investment is favorable to Sri Lanka’s future aspirations, and is not undertaken with the intention of inflaming regional power politics.

The Asian Century

The initial decades of the new millennium have often been tagged as the “Asian Century” – a projected shift of power back to the continent after its deep slumber in the socio-economic hinterlands. As the curtains rise on this rejuvenated stage, the limelight shines bright on China. Its plans for the future have ramifications for all Asian nations, Sri Lanka included. Only time will tell if such plans and policies usher in a shift in the global paradigm.

(Vishvanathan Subramaniam is a Research Assistant Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka)

10 Jan 2025 1 hours ago

10 Jan 2025 1 hours ago

10 Jan 2025 3 hours ago

10 Jan 2025 3 hours ago

10 Jan 2025 3 hours ago