12 Jun 2017 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Following is a presentation made by Rohan Samarajiva to the People’s Commission for National Policy on International Trade recently.

Following is a presentation made by Rohan Samarajiva to the People’s Commission for National Policy on International Trade recently.

We must look to the future, not the past. We must be realistic about where we are at present and what our potential is. We must always take into consideration our external environment, especially the actions of the competitively-positioned countries. We must give priority to the broad public and national interest, not those of narrow interest groups. My brief comments are organised around the

above principles.

1.0 The future is Asia. Most models of international trade assume that greater trade will occur with nearby countries than with those which are far distant. At present, Sri Lanka’s goods exports violate this assumption, going primarily to the US and Europe. This was also the case with the Mode 2 service exports in tourism until recently. But things have changed in tourism service exports, with India and China becoming the principal sources. We must make active efforts to reorient goods exports to Asia because Asia is where the highest growth is occurring. With turbulence in trade policy caused by the failure of the Doha Round of World Trade Organisation (WTO) negotiations and the US withdrawal from the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP), we must focus on plurilateral agreements within Asia, giving primacy to the emerging single market of ASEAN, India and China. Joining some form of ASEAN plus agreement such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) would be optimal. A comprehensive goods, service and investment agreement among the BIMSTEC countries would also be desirable. But bilateral agreements with willing countries are a necessary step for a small economy such as ours to get to the negotiating table where these plurilateral agreements are reached. But the immediate impact of completing the ongoing negotiations will be substantial. Firms located in Sri Lanka, which satisfy the preferential rules of origin stipulated in the various agreements, will have access to a market of three billion people. These firms may be fully owned by Sri Lankan citizens, joint ventures or fully owned by

foreign investors.

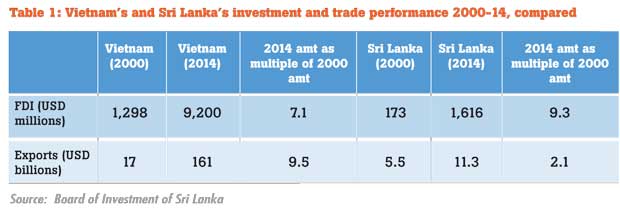

1.1 Both India and Vietnam have entered into multiple bilateral agreements, which is yielding them good results, but also giving rise to the “noodle bowl effect”. But these complications are likely to be reduced when they join the RCEP or a similar plurilateral arrangement. The good results are illustrated by Table 1, which compares Sri Lanka’s and Vietnam’s investment and trade performance. The increase in foreign direct investment (FDI) was in the same range (seven times and nine times); but Vietnam increased exports by 9.5 times versus Sri Lanka’s paltry doubling.

2.0 Trade policy in the 21st century is not a zero-sum game where scores are kept in terms of positive/negative trade balances. In the context of global production networks (GPNs), components of end products (including services) cross and re-cross borders. Here is what the economists at the Central Bank of Sri Lanka say about our failures to catch this wave: “Regional competitors, particularly East and Southeast Asian countries such as China, Taiwan, South Korea, Thailand, Malaysia, Vietnam and Indonesia, have dramatically increased their manufacturing exports through global production networks. India, which traditionally focused on labour-intensive manufacturing exports, has integrated successfully with global production networks producing technology-intensive parts and components for data processing machines, electrical machinery and semiconductor devices. Conversely, only a fraction of Sri Lanka’s manufacturing exports moved through global production networks during this period.”

2.1 GPNs are highly efficient, but they are vulnerable to disruption, as evidenced by worldwide problems caused by the Bangkok floods of 2011. Therefore, firms active in GPNs pay special attention to managing risks, both natural and human in origin. Trade agreements that cover services trade including clear provisions regarding Mode 4 movement of natural persons are important in this regard.

2.2 Sri Lanka’s more efficient logistics and port facilities (relative to South Asia, but not Southeast Asia) may give us an edge in participation in GPNs. That this has not materialized indicates that the legal and regulatory risks are washing out the logistics advantages.

3.0 Services are becoming increasingly important in the economy as a whole and within international economic relations. The first trade agreement to include enforceable provisions on services was the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement of 1987. Sri Lanka is party to the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), which came into effect in 1995. Now every trade agreement includes services. Of the Sri Lankan labour force, 46.5 percent are employed in the service sector, in activities ranging from plucking coconuts to retail trade to software work. This is considerably larger than the 27.1 employed in agriculture and the 26.4 employed in manufacturing. Mode 4 service exports in the form of labour exports yielded earnings (remittances) of US $ 7.2 billion in 2016. While labour exports slowed, earnings grew by 3.7 percent in 2016. Earnings from exports of services recorded a growth of 11.6 percent to US $ 7.1 billion in 2016. About half came from tourism service exports (Mode 2), which yielded US $ 3.5 billion in earnings in 2016, an 18 percent growth over 2015. Earnings from telecommunications, computer and information services increased from US $ 805 million in 2015 to US $ 858 million in 2016. The combined service-export earnings were larger than the US $ 10.3 billion earned from the export of goods. Services are critical inputs for all economic processes, including goods exports. For the overall efficiency of the economy and for improved competitiveness in exports, it is important to enhance competition in service industries, which is best done by opening them to international competition.

3.1 Because service trade across borders requires movement of juridical (Mode 3) and natural persons (Mode 4), there is an unjustified opposition to services trade in general and services agreements in particular. The usual harms associated with protectionism result when domestic suppliers use political pressure to inhibit competition and extract rents in service industries. When protectionism is extended to services that are critical inputs to other economic processes, the overall economy suffers.

3.2 The positive-list method used in services-trade agreements allows for a highly calibrated opening up of sectors and Mode 4 commitments. Unlike in goods agreements, a sector is brought within the scope of the agreement only when it is specifically included and schedules of commitments are offered. Sri Lanka made commitments only in tourism and travel-related services, telecommunication services and financial services in the case of the only services-trade agreement it is party to, the GATS. They too were very conservative and even so, not fully adhered to. Usually, Mode 4 provisions in services-trade agreements affect only professionals, senior managers, etc. Quantitative limits, minimum-salary requirements, etc. can be imposed. This enables the government to assuage the protectionist concerns of organised groups even to the detriment of the overall economy and the interests of the consumer.

3.3 However, given the enormous importance of Mode 4 service exports in the form of expatriate workers travelling to West Asia and elsewhere, we should consider building in safeguards for even non-professionals in the trade agreements that we negotiate. With Sri Lanka now facing labour shortages in critical sectors such as construction, it is time to consider well-designed labour contracts articulated with improved enforcement of immigration laws, as indicated by the proposal to establish an immigration police in the 2017 budget speech.

3.4 The Central Bank says, “Given the stagnant earnings from merchandise exports, the importance of non-traditional service exports has grown significantly, although focused efforts are required to tap their full potential.” To tap the full potential of the service sector, it is necessary to liberalize rules, encourage investment and enable easy movement of professionals across borders. Today, these facilities are available in some form to the Board of Investment (BOI) companies only. Officials have excessive discretionary authority. Workarounds abound.

4.0 Agriculture, where 27 percent of the workforce produces a mere 7.1 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) requires serious attention. The primary focus must be on supporting the initiatives by private firms to increase high-value fruit and vegetable exports that are already underway. This will result in the improvement of standards throughout the sector and will of course improve the earnings of the smallholders now connected to export supply chains. Good agricultural practices including low/no use of chemicals and traceability will increasingly define what is acceptable in export markets. Our trade policies must on the one hand strive to prevent the use of phytosanitary rules as non-tariff barriers. On the other hand, we need to encourage good agricultural practices among suppliers.

5.0 Given China’s success in becoming the factory of the world, many fear that a manufacturing-based path for climbing out of developing-country status is no longer available. High energy costs and labour costs that are high relative to competitor economies are significant constraints in Sri Lanka. That is why only 26.4 percent of our work force is in manufacturing. Therefore, Sri Lanka’s manufacturing option must focus on high-value rather than high-volume manufacturing. This leads to the GPN solution discussed above and the need to reduce the legal and regulatory risks that GPNs are sensitive to, by embedding ourselves in plurilateral or bilateral trade agreements.

5.1 Effective participation in GPNs requires flexibility and certainty about importing as well as about exporting. Old-style import-substitution thinking which seeks to encourage exports while discouraging imports is inimical to effective participation in GPNs. Indeed, some scholars argue that unilateral investment and trade liberalization is superior to bilateral agreements with rigid rules of origin provisions in terms of promoting GPNs.

5.2 Manufacturing enterprises find it difficult to scale up to meet the requirements of GPNs and of regional markets because of labour market constraints. These constraints need to be addressed through labour contracts, rather than opaque workarounds as at present.

6.0 When one looks back at Sri Lanka’s first-generation reforms undertaken in the late 1970s, one sees a form of shock treatment where the domestic market was suddenly opened up with a few safety nets established for those negatively impacted. The reforms that need to be undertaken now are not of the same magnitude. But it is good that the government is considering trade adjustment facilities to help specific firms retool and adjust to increased competition when tariffs, para-tariffs and barriers are brought down.

(Rohan Samarajiva is founding Chair of LIRNEasia, an ICT policy and regulation think tank active across emerging Asia)

07 Jan 2025 7 hours ago

07 Jan 2025 7 hours ago

07 Jan 2025 8 hours ago

07 Jan 2025 07 Jan 2025

07 Jan 2025 07 Jan 2025