12 Aug 2016 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Olympics are not only a revered festival of sports but are also an interesting case study of  economics. The summer Olympics bring together over 11,000 athletes from 204 countries that participate in 42 different sporting disciplines. Over six million tickets are sold while billions join over live broadcasts of the event. Countries vie to host the games by investing large amounts of money and time in preparation, with the expectations that it would bring about growth, development and prestige to the hosting countries.

economics. The summer Olympics bring together over 11,000 athletes from 204 countries that participate in 42 different sporting disciplines. Over six million tickets are sold while billions join over live broadcasts of the event. Countries vie to host the games by investing large amounts of money and time in preparation, with the expectations that it would bring about growth, development and prestige to the hosting countries.

However, some economists argue that although the reasons of wanting to host are many, “none seems more prevalent than the desire for an economic windfall”. The economic toll an event of this magnitude can take on host countries is considerable and the 2016 games preparation at Rio de Janeiro seemed to highlight this predicament.

While the city bid and won the rights to host the games at a time of an economic boom in 2009, Brazil is now facing the deepest recessions since 1901. As a result of its dramatically changed economic fortunes, the city has struggled to adequately prepare for the game.

This article aims to look at the economics behind Olympics and is based on economic analyses carried out by several economists, in particular one by Robert A. Baade and Victor A. Matheson (2016) published in the Journal of Economic Perspectives.

Bidding for the Games

The bidding process itself is no easy task with cities investing vast amounts of money to outdo competition and convince the Evaluation Committee of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to select their city to host the games. Host cities are selected around seven years prior to the event following an open-bidding process and the preparation process includes creating detailed architectural renderings, financial estimates and pre-event marketing. It has been estimated that Chicago for example, spent at least US $ 70 million and Tokyo US $ 150 million for their unsuccessful bids to host the 2016 games.

Host countries are generally expected to bear the entire cost of organising and hosting the Olympics. However, the IOC generally affords some funds for the event. Historically, the host cities used to come from the developed nations – in the period 1896 to 1998, over 90 percent of the hosts came from the developed world. However, developing countries are encouraged to bid with countries like China and Brazil given the opportunity to host the games.

Infrastructure for athletes and visitors

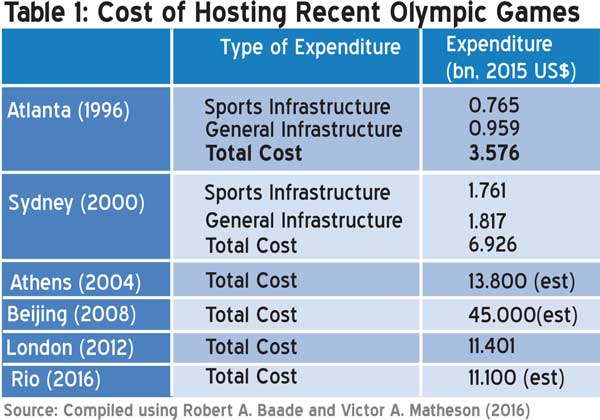

There are three major cost components of the Games. One is the cost of building and developing the required sporting infrastructure of the host city. Given the number of sporting events and their nature, it is unlikely that a particular city would have the entire sporting infrastructure and is most likely that there might be a need to build or expand for instance, a velodrome or a natatorium or a ski-jumping complex.

Another key cost component is the cost of building general infrastructure such as buildings to house the athletes and guests. The IOC requires the host city to have a minimum of 40,000 hotel rooms for spectators and an Olympic Village, which can house 15,000 athletes and officials. This in itself can be a challenge for host cities. For instance, Rio de Janeiro despite being a popular destination had to build 15,000 new hotel rooms to meet this requirement. Although this can have long-term dividends, it may also result in severe overcapacity once the Games are over.

In Norway for instance, following the 1994 Winter Olympics in Lillehammer, 40 percent of the city’s hotels have gone bankrupt. Other general infrastructure costs include the cost of getting the visitors to the sporting venues – Rio embarked on a mass transit extension, which would transport 300,000 daily at a cost of US $ 2.8 billion.

Third are the operational costs, which include opening and closing ceremonies, event management and security. Long being the target of terrorist acts and other possible disruptions, security costs of the Games have escalated rapidly over the years. Security costs of the Sydney Games in 2000 is estimated to be US $ 250 million while that of Athens after four years is said to be around US $ 1.6 billion, an amount that has stayed around the same in the past decade.

Short-run benefits of hosting the Games

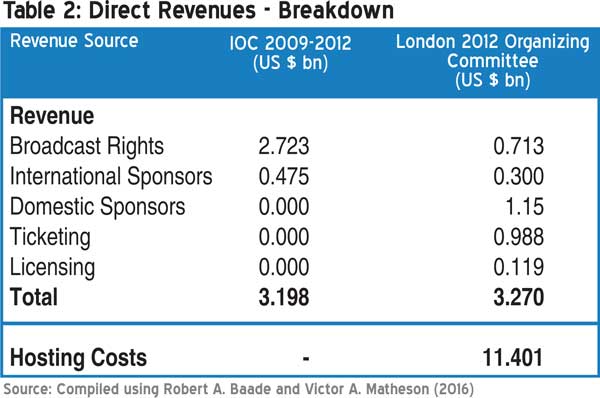

Despite the high costs, short-run benefits of the Games include the boost from construction, tourist booms during the games and significant proceeds from sponsors, ticket sales, licensing and media revenues. While the revenue generated can be divided any way the organisers want to, the ultimate decision lies with the IOC.

The largest source of revenue in recent times has been from television broadcasting rights. However, only less than 30 percent of the revenue was shared with the local organising committee. Further, earnings from international sponsors are split while the host city gets to keep ticket revenue, domestic sponsorships and licensing fees. Table 2 gives a breakdown of the revenue earnings and shows that hosting costs of for example in the London Games was almost four times the total revenue.

Large-scale projects such as that of the Olympics also lead to an increase in economic activity in the short run. Countries with high unemployment may gain from the additional economic activity. However, studies find that the numbers do not meet the expectations. Some cities also show a ‘crowding-out’ effect with a drop in the regular visitors to the city during the games -- Beijing experienced a 30 percent drop in international visitors and a 30 percent decline in hotel occupancy during the month of the Olympics in 2008 compared to the year before.

Long-run impact

Much emphasis has been given to the ‘Olympic Legacy’ created in the host nation. This legacy is seen to include improvements in infrastructure, increased trade, foreign investment and/or increases in tourism that last beyond the Olympics. For instance, the Games are seen to leave a legacy of high-quality sporting facilities that can catalyze improvements in the sport for future generations in the country.

Moreover, investments in general infrastructure can provide long-run returns and improve the standard of living in the host city. Similarly, increased media attention and affiliated coverage on the country can create an allure for tourists to visit the host city and country after the Games. Finally, the Olympics are seen as a means to attract foreign investments as global brands become more familiar with the host city as part of the Olympics or even separately.

The eventual outcome of the Olympic Legacy, however, depends on several factors that determine if the host city is left with a legacy similar to that of Los Angeles (1984) or Athens (2004). The sporting legacy of the Olympics on domestic sporting facilities is one of the most overvalued and evidence suggests that rather than catalyzing sports, the city is left with a heavy burden of building and maintaining facilities that have little to no use beyond the Games. Therefore, these venues effectively become ‘white elephants’ and like many venues used during the Athens 2004 Games, fall into disrepair.

Sporting facilities

In recent years, Olympics hosts have attempted to build stadiums and facilities in order to repurpose after the Games. However, such efforts have rendered limited successes due to the specialized nature of some facilities needed for particular sports, their irrelevance to the sporting culture of the host nation and the expense of conversion. For example, the aquatic centre in Beijing, dubbed the ‘Water Cube’ was repurposed as an indoor water park at a cost exceeding US $ 50 million. Similarly, the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Stadium in London has been converted to a football stadium for West Ham United. However, while the final construction cost was £429 million and the conversion cost exceeded £272 million, the football club contributed only £15 million towards those costs and will be paying just £2.5 million per year as rent on a 99-year lease.

General infrastructure

Unlike specific sporting infrastructure, general infrastructure investments during the Games have the potential to reap benefits in the long term. For example, the Olympic villages in Atlanta and Los Angeles were successfully converted into new dormitories for local universities. Similarly, the city also benefits through heavy investment in improving transport infrastructure within the city as well as access points to and from host venues. Some studies find that investment for the Games do not necessarily provide higher returns than what could be expected if the same investments were made alternatively. However, it is likely that the political will required for urban redevelopment at the scale needed for the Olympics is seldom generated in a vacuum.

The positive returns associated with infrastructure investments, however, depend heavily on the current and future needs of the host city. For instance, the Olympic village in London was successfully converted to a residential apartment complex since a significant demand exists for such housing in London, particularly closer to the finance district. This trend can also be extended to other investments, especially with tourism and hotels. As noted earlier, some believe that media coverage and exposure to a host city can increase the allure of a city as a

tourist destination.

However, this expected increase is unlikely to occur when the said destination is already a popular tourist destination like London or Rio de Janeiro. Barcelona and Salt Lake City are considered success stories in “putting the city on the map” following its hosting duties. At the time, these cities were often overlooked by tourists for better-known destinations, but coverage of the city’s sporting and non-sporting attractions led to an influx of tourists with Barcelona experiencing the fastest growth in tourism among European cities immediately after 1992. Therefore, while hosting Olympics can generate post-Games tourism flows, they are heavily dependent on other factors. Failure to account for these factors may lead to the over-supply of hotels and other facilities that can have a negative knock-on effect on the economy.

A false premise?

Amidst the limited potential for the Games to create positive net benefits for host cities, countries – especially those from developing countries – are increasingly keen to bid. Obviously, the decision to host a global event of such magnitude is not strictly based on economic factors and thus relies heavily on political considerations. Moreover, such events create obvious winners and these bids are often supported by special interests that will benefit most through the event. For example, Boston’s bid to host the 2024 Games was supported by leaders in the heavy construction and hospitality industries.

The overall benefits reaped by Los Angeles and the economic recovery that took place in Barcelona during their respective hosting periods have intensified the attraction of hosting the Olympics. However, the significant difference is that at the time, Los Angeles was the sole bidder and was in a unique position to bargain a beneficial deal for the city.

In contrast, with the deluge of bidding cities, the IOC has greater power in deciding a host city and tends to select one that promises a more expensive and flamboyant event, irrespective of the potential costs. These costs in fact notoriously inflate between the bidding stage and final implementation stage, which exacerbates the issue further. Therefore, countries should be more cognizant of the economic realities and the long-term burdens associated with hosting the Olympics. Thus, the priority should be on a purpose-built Olympics rather than purpose-built stadiums.

(Suwendrani Jayaratne and Kithmina Hewage are Researchers at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). To view the article online and comment, visit the IPS blog ‘Talking Economics’ – www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics)

10 Jan 2025 59 minute ago

10 Jan 2025 1 hours ago

10 Jan 2025 2 hours ago

10 Jan 2025 3 hours ago

10 Jan 2025 3 hours ago