15 Dec 2016 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

At a time when the Employees’ Trust Fund (ETF) is celebrating 35 years of existence, it is time to reflect upon its original concept and perhaps look at any reorientation needs it requires to be compatible with the current socioeconomic environment. The ETF and its sister fund, the Employees’ Provident Fund (EPF), have attracted considerable attention in the recent past. Some concerns are justified while others are unfounded and arise to ignorance.

Most often, whenever these funds come up in conversations, it is surprising to note the many misconceptions that abound. This article attempts to provide some insights into the original concept and objectives of the ETF, correct some of the misconceptions and finally suggest a way forward to achieve desirable objectives.

Concept of an ETF

The open economy introduced in 1978 created a paradigm shift in government policy. The private sector was expected to be the engine of growth, the government was to be a facilitator of economic growth and a massive infrastructure programme was initiated. It was in this environment that the ETF was created. It is common knowledge that the ETF was the brainchild of the then Trade and Shipping Minister Lalith Athulathmudali, who was instrumental in creating the Sri Lanka Ports Authority by amalgamating three entities and making the Colombo Port an efficient and sought-after port.

However, there are two opinions on the exact motive for the creation of the ETF. One belief is the publicly declared objective of making every employee a stakeholder of the economy through indirect ownership of shares in private enterprises. Since the EPF was already an established superannuation fund invested primarily in government securities and principally to benefit employees on retirement, the ETF was to be a non-contributory fund primarily to invest in industrial and commercial ventures and earn a return from such investments for the benefit of members.

The alternative belief was that the government wished to create a new fund, which could be utilised to invest in large infrastructure projects. The government in its endeavour to create rapid economic growth encountered difficulties in financing large infrastructure projects. One such was the dry docks, which was considered essential for the development of the popularity of the Colombo Port.

The story goes that being a brilliant strategist, Athulathmudali after a ‘back of the envelope’ type calculation realized that taking a small sum equivalent to 3 percent of the salaries and wages of all employees would amount to a substantial fund, which the government could use and would be beneficial to the employees as well. The EPF, which commenced in 1958, was turning out to be a very useful captive fund and growing fast.

The EPF funds could not be touched since it had restrictions on investing in commercial ventures. A separate non-contributory fund (contribution by employers only) would therefore be welcome by the working population and also would not be subject to strong objections by employers. This could be an answer to the investment deficit of Colombo Dry Docks Ltd, which was to construct a large dry dock and many other such projects.

Some credence could be given to this belief because a substantial amount of the ETF funds were in fact invested in the Colombo Drydocks, which did not yield any return until its privatization in 1993. Analysis of the ETF’s portfolio of equity investments in 1990 showed that 51 percent was invested in Colombo Dockyard and Drydocks, 18 percent in Dankotuwa Porcelain and 7 percent in Lanka Milk Foods, amounting to a massive 76 percent in three companies, while all other equity investments in several companies amounted to only 24 percent.

In addition, a further Rs.140 million was invested in Colombo Drydocks Ltd as debentures plus Rs.27 million in Lanka Cement debentures. One would not be wrong to assume that the ETF was being used to finance state-owned ventures, which did not yield the desired return. However, one could argue that the investments were within the provisions of the ETF Act and that these investments did actually benefit the country.

By the way, I need to clarify that there existed at that time Colombo Dockyard (Pvt.) Lt, a private company, and Colombo Drydocks Ltd, a public listed company. Colombo Dry Docks Ltd was only a “shell” and the management was handled by Colombo Dockyard Ltd. Later on, after the privatization of Colombo Drydocks Ltd and the liquidation of Colombo Dockyard (Pvt.) Ltd and since most foreign agents were more familiar with the Colombo Dockyard name, Drydocks changed its name to Colombo Dockyard Ltd.

The Colombo Port, which was in the 139th position worldwide in 1980 in the rankings of international container ports, came up to the 26th position by 1988. The ETF could be proud of its contribution in the overall development of the industry and if in fact the ETF was created for investments in infrastructure, as claimed by some, it justifies the intention.

Establishment of ETF

A reference to the establishment of a proposed ETF is seen in the White Paper on Employee Relations published in January 1978. This speaks of a contribution of 6 percent of total earnings of employees to be paid by the employer and credited to individual accounts of the fund to be paid to employees as gratuity.

According to the records available at the Employers’ Federation of Ceylon (EFC), at a meeting held in June 1978, the minister advised the members of trade chambers, associations and the federation that the government intends to introduce legislation to establish an Employee Trust and Investment Fund. The EFC was co-opted to a liaison committee to study and make recommendations on the draft bill, once available. The suggested name at that time, which included ‘Investment’, is significant and hints at the investment objective of the fund.

As per the broad outline of the scheme announced by the minister at the meeting:

Based on this broad outline, the EFC made representations to the trade minister in July 1978, stating inter alia that:

These representations were made on the assumption that the employers would not be called upon to bear any further financial liability under any other scheme. At this time, there was a suggestion in relation to a pension scheme for the private sector employees and a Gratuities Bill to provide for the payment of gratuity for employees. The EFC made it clear that there should not be another burden on the employers in addition to the liability under the Trust and Investment Fund or other schemes that seek to provide for payment on account of the services rendered by the employees.

In August 1979, the press reported, quoting the trade and shipping minister that a new Act setting up an Employees’ Investment Fund will be presented in parliament before the end of the year. “This will provide for the distribution of profits among the workers in the public, corporation and private sectors,” the minister had stated. It was the opinion of the minister that the economy of the country should be equally distributed and enjoyed by everyone.

In January 1980, it was reported that the Employees’ Trust Fund Act, when enacted, would require private sector employers to pay an amount equivalent to 3 percent of the employees’ wages to a special trust fund to provide retirement benefits to those employees. It was further reported that the Sri Lankan scheme is different to those in other countries such as Singapore since the “funds invested on behalf of the employees would come out of their employers’ pockets”. Contrary to the assurances given earlier, in August 1980, just before the ETF Bill was taken up for debate in parliament, the labour minister announced that a Gratuities Bill would soon follow.

During the second reading of the ETF Bill, the trade minister attributed the 3 percent contribution to the fund as an immediate salary increase granted to the workers which would amount to a profitable saving of theirs and that the bill is not in lieu of the gratuity paid to employees.

The Act was passed on October 29, 1980 and has been in effect since 1981. The Act, however, allowed those employers who had voluntarily opted to pay to the EPF a higher contribution than the mandatory 12 percent, to deduct such higher amount up to 3 percent and make contributions to the ETF. The membership of the ETF was higher than the EPF because even those who contributed to private provident funds had to contribute to the ETF.

Objects of ETF

Section 7 of the ETF Act 46 of 1980 lists the following as its objects:

a. To promote employee ownership, employee welfare, economic democracy through participation in financing and investment

b. To promote employee participation in management through the acquisition of equity interest in enterprises

c. To provide for non-contributory benefit to employees on retirement; and

d. To do all such other acts or things as may be necessary for, or conducive to, the attainment of the objects specified in paragraphs a, b and c of this section.

When the ETF Act was passed, some of the objects are reported to have caused much concern in the private sector. Particularly, the item b was feared as it could be used by the government in an undesirable manner. Employee participation in management was another cause of concern. Perhaps the government was inspired by the trends in Sweden and other countries where advanced forms of worker participation existed from the early 1970s.

In Sweden, the workers’ representatives could become members of the board of directors. The Sri Lanka government too introduced this system to government corporations in 1977, which didn’t quite register the expected benefits. By the time the ETF Act became operational, the concept of worker participation in management was dying out. I need to clarify that even today there are many forms of effective worker participation but what I have alluded to was worker representatives on boards of directors.

The closest the ETF has come to having worker participation was when a union representative was nominated to the board of Dankotuwa Porcelain by the labour minister under whom the ETF functioned at that time. The ETF by virtue of the fact that it had 50 percent ownership of Dankotuwa Porcelain was able to make that nomination. This was not a successful decision.

I recommend that this dangerous object clause be removed, since it is clear that the fears of the Employers’ Federation were justified when later the ETF acquired significant stakes in companies, which were being privatised, thus completely defeating the objective of privatisation. In one instance, the ETF acquired 90 percent of the equity of a company being privatised.

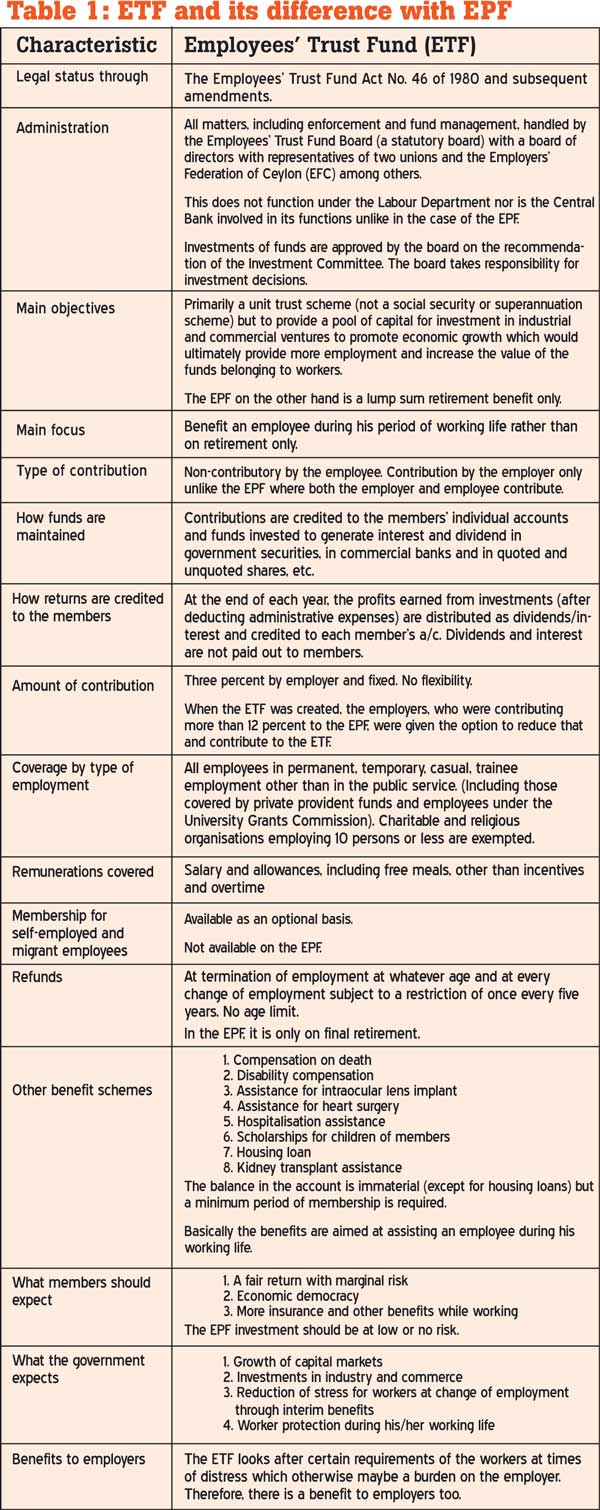

By and large, the object for which the ETF was formed has been achieved but it was in the early 1990s that a clear identification of what the ETF stands for and the difference between the EPF and ETF was made. This enabled many who argued that the ETF was a mere duplication of the EPF to realise the difference. Table 1 indicates the clear demarcation and the objects in line with the prevailing business and industrial relations climate at the time without deviating from the objects specified in the Act. Perhaps it is time to revisit this and redefine the objectives in line with the current requirements.

It was in line with this clear definition that more benefit schemes were initiated by the ETF. The heart surgery scheme was a great boon to the workers who could not afford the surgery. There was criticism that this scheme would not benefit the manual workers in the mistaken widely held belief that only the senior executives who suffer from work stress succumb to heart problems. This was debunked by many heart specialists and the evidence from the claims too prove that many manual and clerical workers benefited from this scheme.

The disability scheme and death benefit scheme as well as the intraocular lens implant scheme were also based on recommendations of medical professionals who knew of the difficulties of the less affluent workers. When the ETF reflected on the various schemes, it realised that all the hitherto initiated schemes were to assist negative situations and so decided that a scheme for a positive event was desirable. This gave birth to the Year 5 scholarship scheme, which lightened the burden of the members whose children were star performers and gained admission to better schools.

Fund in safe hands

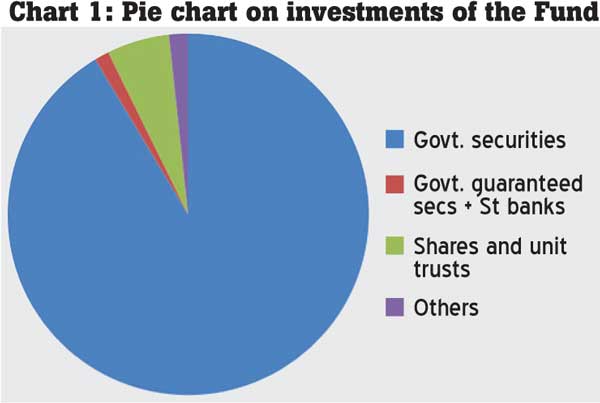

There is an unfounded fear among many uninformed members that their savings are not actually available because the government has appropriated them. Even educated private sector managers have expressed this fear. Often an explanation has enlightened them but not everyone is convinced. More communication is required to educate employees that their funds are safe. If one looks at the latest portfolio as seen in the pie chart, there should be no doubt that the funds are safe.

Chart 1: 91 percent is in government securities and only 5.6 percent is in shares and unit trusts. This chart should allay any fears that people have regarding the security of their funds. However, this certainly does not mean that the board should be callous in its equity investment policy. Every investment, however small, must be transparent and justified. The investment in shares is grossly insufficient and defeats the purpose for which this fund was set up.

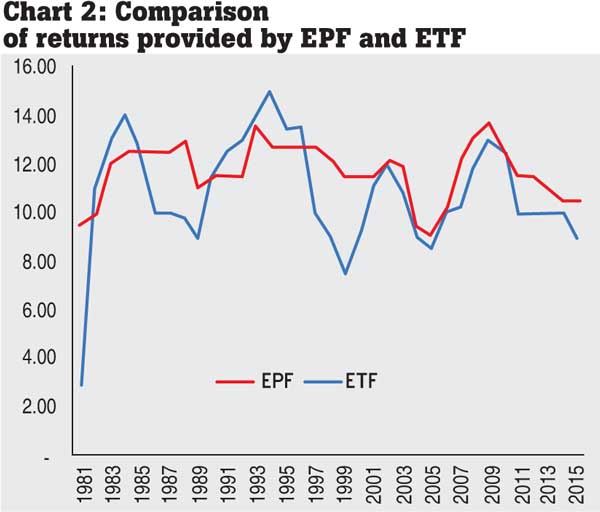

A separate study is required to determine whether the EPF and ETF have at least provided a fair return at least equivalent to the savings interest rate of the National Savings Bank.

Chart 2: The chart clearly shows that the EPF returns are more stable while the ETF returns are more volatile. The actual situation of the ETF returns may be even worse because the correct loss provisions for the diminution of the market value of shares had not been made in some years and the Auditor General had even pointed this out in his report. The ETF may not be able to match the EPF returns because the ETF has medical, insurance and scholarship benefits, the costs of which are set off from the profits of the fund. Furthermore, the entire administrative cost of enforcement is set off against the profits whereas in the case of the EPF, the enforcement activities carried out by the Labour Department are provided by the Labour Department budget.

Way forward: Some suggestions

1. The fish rots from the head, they say, meaning that a strong and competent board is a sine qua non for any institution. A major lapse in the Act is that the Commissioner General of Labour is not an ex-officio member of the board. The provision to have a nominee of the minister in charge of the subject of trade is no longer relevant and should be replaced perhaps with a nominee of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka. The four members nominated by the minister should include qualified and experienced professionals in the fields of industry, commerce and banking. During the tenure of the previous government only one representative of trade unions was appointed. This is not desirable. It is also desirable to have the EFC chairman as an ex-officio member rather than leaving it open for the EFC to decide on the nominee.

2. Governance could be improved by making the board of directors more accountable.

I suggest that the National Labour Advisory Council has a quarterly agenda item where the performance of the ETF and its investment decisions are subject to discussion.

3. The objects of the fund should be revised taking cognisance of contemporary requirements. My suggested objects are as follows:

a. To promote economic growth and employee democracy through participation in financing and investment

b. To provide for non-contributory medical, insurance and financial benefits to employees during their working life and on retirement

c. To promote employee welfare, occupational health and safety

d. To promote industrial harmony and higher labour productivity through the promotion of modern techniques of employee involvement and employee engagement

e. To do all such other acts or things as may be necessary for, or conducive to, the attainment of the objects specified in paragraphs a, b, c and d of this section

4. Section 9 should be repealed. It allows the board to establish and operate industrial and commercial enterprises and secure shares for employees in any undertaking to promote employee participation in the management of such undertakings. The investment policy should be precise and unambiguous. The focus of the investment should only be confined to realising a fair return at a marginal risk. The fund should not take any strategic stake in any enterprise and ideally should limit the holding of any company to 10 percent of its issued capital.

The fund should not invest directly in unlisted equities nor should it invest in start-ups. The experience of the fund in such start-up investments has been disastrous. If the fund wishes to contribute to economic growth it could invest in venture capital funds, which have an abundance of experience in evaluating projects suitable for support.

5. Many years ago, the ETF carried out a safety campaign with TV commercials. It later joined with CTC Eagle Ltd to promote a National Safety Award with technical assistance provided by the Factories Division of the Labour Department. I believe the ETF has an obligation to promote occupational health and safety and should actively support such programmes to elevate the health and safety environment in the workplace.

6. When the Katunayake Export Processing Zone was reaching its peak in the early 1990s and there was a massive influx of workers to the zone but with woeful accommodation conditions and the safety of female workers was at risk, the ETF stepped in, joining with the Board of Investment (BOI) to increase the quality and quantity of accommodation. This too was in line with welfare of workers.

7. In another exercise, when statistics revealed that the percentage of low birth weight babies in Sri Lanka was high compared with other South Asian nations, perhaps because of a higher percentage of working females, the ETF stepped in and in consultation with Sri Lanka’s nutritionists initiated a programme of advice to employers and employees. Research carried out in India has proved that a healthier workforce will be more productive, will make lesser errors and will be less prone to accidents. Therefore, through such interventions, the ETF could play a significant role in enhancing the competitiveness rankings of Sri Lanka.

There are moves currently to amalgamate the ETF and EPF. I hope the policymakers would not lose sight of the useful objects of the ETF and would formulate two funds to be managed by one body and continue the programmes that would benefit employees during their working life and continue to promote those techniques, which would provide a safer workplace and create healthier workers.

(Sunil G. Wijesinha was Chairman of the Employees’ Trust Fund Board from 1989 to 1994. He subsequently served on the board of directors on three other occasions. He is a chartered engineer, a chartered management accountant and a qualified productivity practitioner. Currently he serves as a management consultant and is Chairman of listed and unlisted companies. He was a former Chairman of NDB Bank and a former Deputy Chairman of Sampath Bank and held the posts of Chairman of the Employers’ Federation of Ceylon and President of the National Chamber of Commerce of Sri Lanka)

10 Jan 2025 20 minute ago

10 Jan 2025 37 minute ago

10 Jan 2025 57 minute ago

10 Jan 2025 2 hours ago

10 Jan 2025 2 hours ago