17 Jun 2016 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

In view of the inflationary pressures and high import demand that arose from the easy money policy,

In view of the inflationary pressures and high import demand that arose from the easy money policy,  the Central Bank began to adopt a tight monetary policy early this year.

the Central Bank began to adopt a tight monetary policy early this year.

While it has helped to mitigate demand pressures to a certain extent as elaborated in my last week’s column, excessive bank credit supply to the private sector continues to persist. Hence, it has become imperative to further tighten monetary policy to mop up excess liquidity so as to arrest core inflation and to curb import demand.

Policy Rate hike

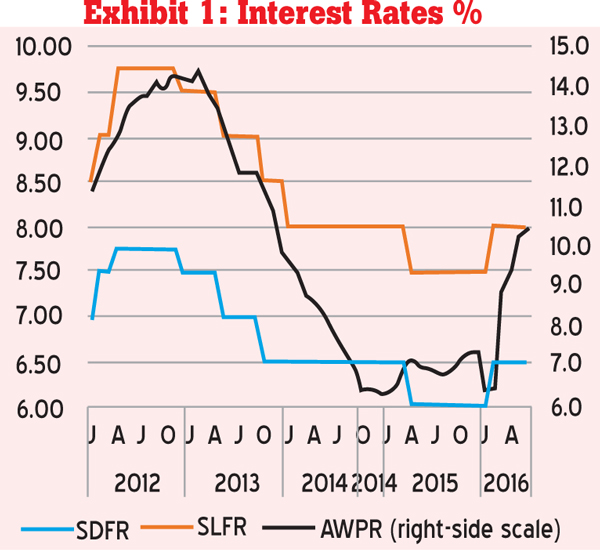

The Central Bank had reduced its policy rates continuously since December 2012, as shown in Exhibit 1. The Standing Deposit Facility Rate or SDFR (rate applicable for placement of overnight excess funds of commercial banks)was brought down in several steps from 7.75 percent in April 2012 to 6.00 percent in April 2015. The Standing Lending Facility Rate or SLFR (rate applicable for lending of overnight funds to commercial banks) was reduced from 9.75 percent to 7.50 percent during the same period.

Departing from the relaxed policy stance, the Central Bank tightened monetary operations in January by raising the Statutory Reserve Ratio (SRR) from 6.0 percent to 7.5 percent. This was followed by an increase in the Standing Deposit Facility Rate and Standing Lending Facility Rate by 50 basis points to 6.5 percent and 8.0 percent, respectively in February.

In line with the increase in policy rates, the market rates which were at low levels have begun to rise as reflected in the commercial banks’ Average Weighted Prime Lending Rate (AWPR).

Treasury Bill and Bond yields up

The yield rates on government securities too have risen since last year. The Treasury Bill rate rose significantly in the primary market in March last year due to the removal of restrictions placed on the SDF by the Central Bank and market anticipations for higher government borrowing requirements in the midst of a slowdown in foreign capital inflows. The Central Bank claims that its decision to issue government securities only through public auctions also contributed to the upward shift of the yield rates reflecting market realities.

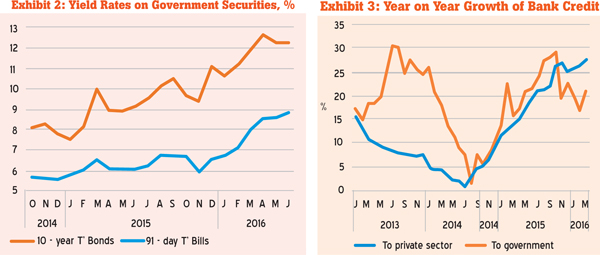

The yield rates in the secondary market rose in recent months as shown in Exhibit 2. At the shorter end, the 91-day Treasury Bill rate rose to 8.60 percent in end-May 2016 from 6.06 percent a year ago. The 10-year Treasury Bond rate was up from 8.86 percent to 12.29 percent.

Relaxed monetary policy created credit bubble

The cumulative effects of the loose monetary policy on private sector credit growth were evident from mid-2014 onwards as shown in Exhibit 3. The average annual increase of commercial bank credit to the private sector was high as much as 27 percent in the first quarter of this year.

The government borrowings from the banking sector too shows an increasing trend since mid-2014. As the government security market experiences a capital outflow since last year, similar to other emerging market economies, there is an increasing burden on the domestic Treasury Bill and Bond markets. Nevertheless, bank lending to the government has declined since the latter part of last year reflecting lesser monetary accommodation.

The impact of the rapid increase in bank credit was reflected in the broad money supply which rose at a year-on-year growth rate of 19 percent in March 2016 compared with a 13 percent growth a year ago. The faster growth of money

supply has led to exert demand pressures on inflation and consumer goods imports.

Low interest rates did not boost investment

The easy monetary policy did not bring about any boost to investment or to GDP growth, as expected. It is rather unwise to anticipate an increase in private investment merely by means of low interest rates, as there are so many other economic and non-economic factors that influence investment.

Business decisions are mostly based on comparisons between the expected rate of return on investment and opportunity cost of investment. Interest rates represent the opportunity cost. Expectations are influenced by many factors including macroeconomic economic environment, technological changes, exchange rate volatility, capacity utilization, export competitiveness, aggregate demand, fiscal stability, inflation, political stability, business confidence, availability of credit and cost of production.

Given the country’s poor track record on most of those attributes, domestic investment remained stagnant despite the reduction in interest rates. Following the cessation of the war, private sector investment showed a gradual increase from 17.3 percent of GDP in 2009 to 22.4 percent by 2012. Since then it has stagnated at

the same level reflecting non-response of private investment to interest rate cuts.

Demand pressures on inflation and imports

The low interest rate environment encouraged consumption, as savings gave low returns. Thus, low interest rates had a dampening effect on domestic savings. This is reflected in the downfall of domestic savings ratio from 24.6 percent of GDP in 2013 to 22.6 percent in 2015.

As the low interest rate policy was coupled with a less-flexible exchange rate system until last year, there was bias towards imports vis-à-vis exports thus, overburdening the balance of payments. The overvalued rupee and low interest rates made imported goods relatively cheaper. The influx of consumer durables, particularly vehicle imports, in recent years amply validates this point.

Speculative transactions thrived

It is empirically found in many countries that pushing down interest rates on financial instruments to low levels by monetary authorities leads to distort investment decisions and to create asset bubbles. The surplus-fund holders tend to move to different alternative assets such as commodities, real estate and risky financial instruments.

Meanwhile, speculators are encouraged by low interest rates to borrow funds and acquire assets in the monetary loosening environment. This kind of boom in short-term profit making results in a surge of asset prices leading to “asset bubbles”, thus creating adverse effects on financial stability as experienced by the East Asian countries during the financial crisis in the late 1990s.

Monetary tightening imperative

The recent shift in monetary policy towards contractionary stance along with rupee depreciationis inevitable to curb the excessive credit demand from the private sector entities and individuals for purposes such as luxury goods imports and speculative trading which had no bearing on productive investment or GDP growth. Continuation of low interest rate policy coupled with an overvalued rupee would have led the country towards a deep financial crisis. The current trends indicate that market liquidity continues to remain high despite the rate hike, and therefore, further monetary tightening is essential.

Meanwhile, the expansionary effects of government’s bank borrowings on the money supply cannot be underestimated. The budget deficit is projected to remain around 5 of GDP in the medium-term implying large borrowing requirements.

Although certain tax revisions have been introduced recently to augment the revenue, no effective steps have been taken yet to cut down government expenditure. Monetary policy needs

to be supported by fiscal consolidation with bold steps to prune unproductive public expenditure.

(Prof. Sirimevan Colombage,

an economist, academic and former senior central banker, can be reached at [email protected])

10 Jan 2025 23 minute ago

10 Jan 2025 1 hours ago

10 Jan 2025 2 hours ago

10 Jan 2025 4 hours ago

10 Jan 2025 4 hours ago