02 Feb 2018 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

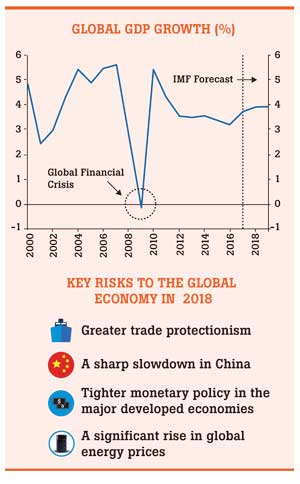

The world economy appears to be booming – in its latest World Economic Outlook Update, published on January 22, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimated that global gross domestic product (GDP) grew by 3.7 percent last year, up from 3.2 percent in 2016, which is the fastest rate of expansion since 2011.

The world economy appears to be booming – in its latest World Economic Outlook Update, published on January 22, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimated that global gross domestic product (GDP) grew by 3.7 percent last year, up from 3.2 percent in 2016, which is the fastest rate of expansion since 2011.

What’s more, this pick up in the global economy has been unusually broad-based. GDP growth has strengthened across the developed world, driven by stronger export and investment growth, while the major emerging economies have also performed well.

This suggests that the world economy is finally shaking off the effects of the global financial crisis a decade ago. Indeed, the early signs indicate that last year’s strong momentum has carried over into 2018, with most forecasters expecting another solid year for global growth.

While this period of greater economic dynamism is to be welcomed, there are significant risks that should not be ignored, particularly in the case of a small open economy like Sri Lanka with significant external vulnerabilities. Four major risks to the global economy that are worth watching are:

(i) The spectre of greater trade protectionism

While the world trading system made it through the first year of the Trump presidency relatively unscathed, the risk of a lurch towards protectionism has not disappeared. In fact, if anything, this risk looks more likely to come to a head this year than last. In the specific case of the US, the outcome of the talks to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) is a key thing to watch, to get a sense of whether fears of greater protectionism are well founded

or not.

While Sri Lanka is not part of the NAFTA, the US withdrawing from the trilateral trade agreement would bode ill for the future of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and suggest that a trade war between the US and China is quite likely. This would benefit neither economy and have a knock-on impact on the rest of the world, including Sri Lanka.

Brexit is less of a risk to the global trading system but negotiations between the UK and EU are also worth monitoring, particularly given that the UK is Sri Lanka’s second largest

export market.

(ii) A sharp slowdown in China

While the official GDP data imply that the Chinese economy continues to do very well, with the economy expanding by 6.9 percent last year, most analysts agree that this data may not reflect what is happening on the ground.

Indeed, while it seems clear that the Chinese economy picked up in 2017, there are some signs that it started to slow in the final months of last year as the government tightened credit conditions. If this is right, we may see the resurgence of worries that the Chinese economy is heading for a so-called ‘hard-landing’, which rocked financial markets in late 2015 and early 2016. At the very least, this would lead to a tightening of global financial conditions that would weigh on demand in Sri Lanka’s key exports markets in Europe and the US.

(iii) A tightening of monetary policy in major developed economies

The pickup in global growth has not yet triggered a substantial rise in inflation and there are a few signs of upward pressure on wages. But as their economies strengthen, central banks in Europe, Japan and the US are increasingly turning their attention to tighter monetary policy.

The risk is that a sudden surge in inflation leads to policy interest rates being hiked much more quickly than financial markets currently expect, sparking a selloff in these markets and setting the stage for the next global economic downturn. This prospect appears most likely in the US, where President Trump has just delivered a fiscal stimulus to an economy that, by most measures, is already running at close to full capacity and so could trigger a sharp rise in inflation. The main risk for Sri Lanka here too is from tighter global financial conditions and weaker demand in its key markets.

(iv) A significant rise in global energy prices

This is perhaps, the risk least likely to crystallise in 2018 – as things stand, the demand and supply fundamentals are more consistent with a slight fall in global oil prices from around US $ 70 per barrel now to US $ 50-60 per barrel. But a war in the Middle East, perhaps an open conflict between Iran and Saudi Arabia, unlikely as it is, would send oil prices skyrocketing.

This would significantly increase the cost of Sri Lanka’s energy imports and put serious pressure on the country’s already strained balance of payments position, not to mention its limited foreign exchange reserves.

Admittedly, there are upside risks to the outlook for the world economy too and it is possible that we could be in the early stages of a prolonged upturn in global growth. But the lesson of the global financial crisis is that good times don’t last.

Sri Lanka must use the current benign conditions in the world economy to ensure that it is ready to withstand the next global downturn when (not if) it comes. To this end, rather than using the current strength of the world economy as an argument to slow the current reform efforts, Sri Lankan policymakers should leverage it as a compelling reason to

push ahead.

At the same time and within bounds of the country’s current IMF programme, fiscal and monetary policy should be set in a manner that takes account of the risks lurking in the global economy. If we achieve all this, there is every chance Sri Lanka will have a prosperous 2018.

(Adam Collins is a Research Fellow at the Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute of International Relations and Strategic Studies (LKI). This commentary is based on his presentation at the Ceylon Chamber of Commerce on January 22, 2018. The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and not the institutional views of LKI and do not necessarily reflect the position of any other institution or individual with which the author

is affiliated)

01 Jan 2025 14 minute ago

01 Jan 2025 46 minute ago

01 Jan 2025 1 hours ago

01 Jan 2025 2 hours ago

01 Jan 2025 5 hours ago