16 May 2017 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

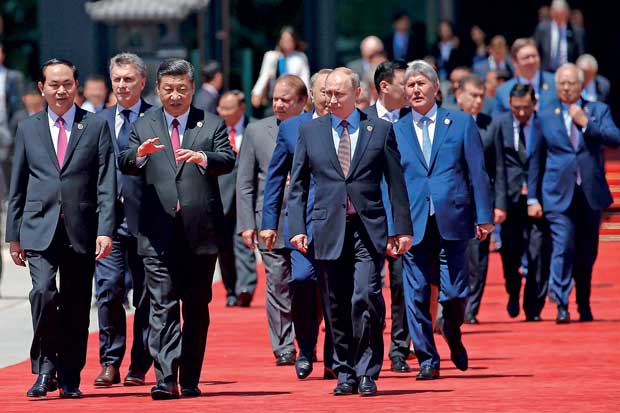

In Beijing on Sunday, Chinese President Xi Jinping hosted a global summit on his Belt and Road Initiative under the aegis of the National Development Reform Commission’s (NDRC) China Centre for International Economic Exchanges (CCIEE), NDRC’s top think tank. This is part of a massive exercise in international diplomatic communication.

In Beijing on Sunday, Chinese President Xi Jinping hosted a global summit on his Belt and Road Initiative under the aegis of the National Development Reform Commission’s (NDRC) China Centre for International Economic Exchanges (CCIEE), NDRC’s top think tank. This is part of a massive exercise in international diplomatic communication.

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is China’s boldest attempt yet to spell out the way it might engage with the world, seeking more certainty in its relations with neighbours across Asia and countries around the world.

The genesis of the idea is important. It derives from China’s ancient links with its trans-Asian neighbours. They are the countries on which the impact of China’s rise will be most immediately and keenly felt.

The BRI is a major Chinese strategy for achieving sustainable development through strengthening connectivity with partner countries and realising mutually beneficial economic relations. As David Vines says, though there are risks in its delivery, the BRI presents ‘a huge opportunity’. It offers a framework for deepening international economic cooperation through a platform of open regionalism that promotes economic integration through deepening five types of links, namely: policy, infrastructure, trade and investment, financial and people-to-people exchanges.

Of these five types of links, a priority is put on infrastructure connectivity. This type of connectivity is about the building and financing of roads, rail, gas pipelines, oil pipelines, electricity and telecommunications connectivity between the participating countries.

It also includes building of major economic corridors and ports that facilitate the flows of goods, capital, technology, people and information. Infrastructure connectivity is an important part of economic development, the deepening of which should significantly ease bottlenecks on growth and help deepen trade, investment and financial integration.

The BRI has two defining characteristics: it is a framework for spelling out the connectedness between China’s domestic development and external challenges and it is a framework for inviting partners around the world to join with China in defining the arrangements through which mutual benefits in the relationships with China can best be realised.

What are the principles and platforms that the BRI promotes for the building of these different types of connectivity?

Importantly the BRI adopts the principles of open regionalism that welcome the participation of countries around the world. Partners can take part in the cooperation at any level and in whatever the area best suits their needs and priorities, domestic conditions and readiness for international cooperation. Through an open and inclusive platform, free trade and investment and financial integration can be promoted, ‘consult, jointly build and share’ principles can be put into practice, ‘mutual learning and mutual benefit’ can be pursued and joint development can be realised.

Upholding free trade principles and deepening economic integration are what the world now needs in the context of slow global growth and a rising tide of anti-globalisation, given its latest kick-along by Trump’s elevation to the White House in Washington.

The world can welcome commitment to these principles. It can recognise the upholding of these principles through the BRI as the demonstration of Chinese support for, and contribution to, the international public goods and economic leadership that the region and the world needs for achieving more sustainable growth and development. Based on close consultation and cooperation, the initiative can be seen as an important opportunity for diversifying and strengthening China’s bilateral, regional and global cooperation in a multitude of institutional arrangements that promote both economic and political security.

There are two main risks. The first relates to China’s own policy in developing the BRI. Although China has described the initiative as inclusive and designed to create mutual benefit, this will not be easy and will require a huge effort in international cooperation. The second interdependent risk relates to the policies that other countries adopt towards China and the extent to which the principles of engagement take multilateral interests into account.

BRI’s economic rationale

In this week’s lead, James Laurenceson observes that “Australia’s reluctance to participate in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) harks back to its slow entry into the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). … The economic case for supporting the AIIB proposal was always overwhelming. But under pressure from the United States, then Prime Minister Tony Abbott initially rejected China’s invitation. In explaining his stance, the former prime minister echoed US claims that the AIIB wasn’t a truly multilateral institution and that its governance standards would be lacking.”

The logical approach was of course not to stay out but to join, guaranteeing a more multilateral approach. When the United Kingdom and other European countries signed on, Australia did too.

Like the AIIB, the BRI also has a clear economic rationale, driven as it is by China’s economic leadership team. But it is also of considerable and positive strategic importance, committing China to cooperative endeavours at a time when the old industrial world is in retreat on global engagement. These are essential ingredients to success.

China is in the process of defining an external economic engagement strategy for exporting its goods, capital, know-how, standards and influence. It has opened the door for other countries to help define how that might be shaped and ultimately received. In a world without the Belt and Road strategy the world (and China) would be much less clear on how China’s engagement with other countries will play out as its economic interests, influence and weight all grow.

The idea that the BRI is prescriptive in nature misunderstands totally what it offers. In fact, as the summit in Beijing again makes clear, it sets out an opportunity and poses a question about what other countries want from China and how they would like to engage with it. It provides a slate on which to draw out how the relationship with China needs to be shaped.

There’s no doubt that there is much at stake in the BRI for China, beyond the narrow benefits of international economic integration substantial though they may be. In constructing this network of cooperation with its partners, the perception of China as part of the positive development strategies for neighbouring countries is enhanced. Apart from stimulating domestic growth and international progress that will eventually attract powerful diplomatic and political capital.

Even the most negative will be encouraged to concede that China cannot be so easily cast as a belligerent, assertive and self-interested actor. It’s useful both to China in seeking a more understanding hearing in the world and it’s useful to China’s partners, who have so far lacked a proper framework for their relations with China, to have more optimal engagement in this

multilateral setting.

A US–China joint statement released a day before the summit has said that the ‘United States recognizes the importance of China’s One Belt and One Road Initiative’ and in a promising sign the US government sent a delegation to the summit. The United States might seek to capitalise on China’s initiative in the context of the progress being made on bilateral trade issues, which could be a game changer for broader membership of the BRI, US–China cooperation and elevating while putting disciplines

on the BRI.

The success or failure of the BRI, not only for China’s economic diplomacy but also for outcomes in the global economic regime, will depend on whether countries like Australia and the European powers make the choice to sign on in the spirit of multilateral engagement as they have with AIIB. The alternative is a world of transactional bilateral deals that threaten to corrode the openness of the global economic regime, already at serious risk.

(Courtesy East Asia Forum)

(The EAF Editorial Group is comprised of Peter Drysdale, Shiro Armstrong, Ben Ascione, Amy King and Jillian Mowbray-Tsutsumi and is located in the Crawford School of Public Policy in the ANU College of Asia and the Pacific)

08 Jan 2025 46 minute ago

08 Jan 2025 2 hours ago

08 Jan 2025 3 hours ago

08 Jan 2025 4 hours ago