23 Feb 2017 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The international prices of liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) have been rising sharply over the last few months, breaking away from a relatively stable trend seen in the recent times, which may suggest that a permanent shift in prices is taking place.

The international prices of liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) have been rising sharply over the last few months, breaking away from a relatively stable trend seen in the recent times, which may suggest that a permanent shift in prices is taking place.

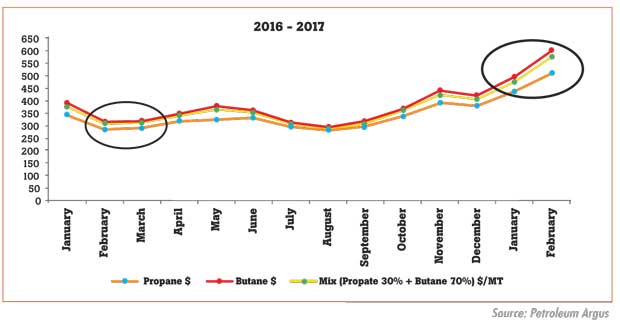

During most of 2016, the main components of LPG, butane and propane, fluctuated within a narrow range. The spot price for propane, which is cheaper, was around US $ 285 to US $ 340 a metric tonne.

Butane, which is more expensive, was around US $ 320 to US $ 390, according to Petroleum Argus, which compiles the energy commodity data.

But over the last four months, the prices have climbed steadily.

Propane rose from US $ 285 a tonne in September 2016 to US $ 510 by February 2017. Butane went up from US $ 320 in September to US $ 600 by February 2017.

Over the past 18 months, the crude oil prices have also started to move up (from around US $ 30 a barrel for West Texas Intermediate to around US $ 56 a barrel now) but the prices of some refined products like propane and butane have risen much faster.

In Sri Lanka, LPG or cooking gas has more butane than propane. Propane makes up only 30 percent of LPG, while the more expensive butane accounts for 70 percent. Based on this mix, a metric tonne of LPG, which cost US $ 376 in January 2016, would cost US $ 573 a tonne in February 2017.

This is a sharp 52 percent rise in costs over a little more than a year.

A formula raises prices gently. But if the prices are not adjusted on a timely manner, a large increase may be required later.

In the meantime, the petroleum product retailers will make losses.

The independent economists in Sri Lanka have been calling for formula-based pricing of petroleum products including diesel and petrol to prevent the economy from being destabilized by energy company losses.

Because petroleum is imported, the losses have a direct impact on the balance of payments.

When the oil prices rise, the oil companies have to pay more money to import. If they cannot sell and recover their costs, the losses then have to be funded by borrowings from the banking sector. In the past, these losses have led to economic instability, involving a fall in the rupee and sharp rises in both interest rates and retail fuel prices.

“The large losses in the Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB) and Ceylon Petroleum Corporation (CPC) have helped trigger balance of payments crises in 1999/2000, 2009 and 2011/2012,” Advocata Institute, a Colombo-based independent think tank, said in the report ‘State of State Enterprises’, last year.

“During the 2011 crisis, the bank-financed cash flow deficits at CPC totalled Rs.117.5 billion. At the CEB, it was Rs.10.8 billion.

When the state banks are compelled to finance losses at state enterprises, the investible funds collected from the public are misused for consumption,” the think tank added. When the investment is reduced, long-term growth and job creation suffer. When the prices are held down for long periods and suddenly raised, it also hits consumers as a shock.

“It is important to have a credible, transparent and predictable fuel pricing mechanism so that the firms and individuals alike can adjust their economic activity accordingly,” Ceylon Chamber of Commerce Chief Economist Anushka Wijesinha

wrote last year. “This will help consumers (firms and individuals) benefit better during oil price drops and will ensure state entities involved in fuel supply don’t suffer from having to keep artificially low prices during oil price rises.” When people get subsidized energy, they will continue to import and consume other goods, creating an economic imbalance. If the prices are kept close to market, non-fuel consumption has to adjust, keeping the internal and external demand in balance, preventing any

economic instability.

When the energy retailers are government owned, the Treasury has to use the taxes collected from the people - which are better spent on health and education - to repay loans and bail them out.

To prevent negative fallouts, timely price adjustments are needed for all types of fuels.

In recent years, the LPG sector has not been a burden on the tax payer or a source of economic instability. But this is no longer true. Increasingly, the industry analysts believe that the price rises seen now are not a temporary phenomenon. There were expectations earlier that the prices will come down after the northern hemisphere winter. But that has not happened.

09 Jan 2025 31 minute ago

09 Jan 2025 2 hours ago

09 Jan 2025 3 hours ago

09 Jan 2025 3 hours ago

09 Jan 2025 3 hours ago