09 Jun 2016 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The Central Bank has introduced a contractionary monetary policy stance recently so as to rectify the economic fundamentals that had been in disarray for a long time. The relaxed monetary policy adopted hitherto propelled aggregate demand exerting severe pressures on inflation and balance of payments while reflecting high GDP growth rates.

In response to the restrictive monetary policy measures, the interest rate structure has moved upward in recent weeks thereby helping to mop up excess liquidity. Nevertheless, the monetary and real sectors seem to take a longer time to react to the monetary tightening, given the acute fiscal imbalance and adjustment lags.

Suppressed interest rates overheated the economy

The Central Bank had continued a loose monetary policy stance since 2012 until early this year by  way of cutting down its policy (interest) rates. Consequently, the yield rates on government securities declined easing the cost of government borrowings. Interest rates for deposits and advances of commercial banks and other financial institutions too declined. While maintaining a low interest rate regime, the Central Bank defended the rupee by selling its foreign reserves to the market. This led to stabilize the rupee at an overvalued exchange rate.

way of cutting down its policy (interest) rates. Consequently, the yield rates on government securities declined easing the cost of government borrowings. Interest rates for deposits and advances of commercial banks and other financial institutions too declined. While maintaining a low interest rate regime, the Central Bank defended the rupee by selling its foreign reserves to the market. This led to stabilize the rupee at an overvalued exchange rate.

The low interest rates and the overvalued rupee had many adverse economic consequences as reiterated in my previous columns. The low interest rates boosted consumer demand creating inflationary pressures. They also augmented the demand for consumer goods imports, particularly vehicles, causing balance of payments problems.

In my article appeared in the Business Times of February 16, 2014, it waspredicted “When demand pressures on imports build up due to credit growth supported by low interest rates, the authorities will have to give up exchange rate stability at some stage. The other choice is to give up the low interest rate policy stance. It is not practicable to have the best of both worlds for a long period as amply demonstrated by the impossible trinity theorem.”

This is what we are experiencing now. In the face of the rising core inflation and high import demand created by excessive credit growth, interest rates are on the rise along with the depreciation of the rupee. Had the Central Bank allowed the market to adjust the exchange rate and interest rates more freely prior to 2015, a harsh interest rate hike or an intense rupee depreciation in the subsequent years could have been avoided to a great extent.

Monetary tightening begins

The surge in foreign capital inflows prior to 2015 had helped to sustain low interest rates and rupee overvaluation simultaneously. Emerging market economies like Sri Lanka had greater access to low-cost funds in the global capital markets due to the near-zero interest rates in the US and European capital markets. Things changed dramatically last December when the US Fed raised the policy rates abandoning its 7-year long Quantitative Easing (QE). It not only raised borrowing costs for emerging markets but also led to capital outflows from these countries.

Domestically, monetary tightening has become inevitable now to arrest the exorbitant rise in consumer goods imports and the picking up of core inflation. In January this year, the Central Bank raised the Statutory Reserve Ratio (SRR) from 6.0 percent to 7.5 percent. This was followed by an increase in the Standing Deposit Facility Rate and Standing Lending Facility Rate by 50 basis points to 6.5 percent and 8.0 percent respectively in February. The effects of these policy changes are being gradually transmitted to money and capital markets.

Treasury yield curve moves up

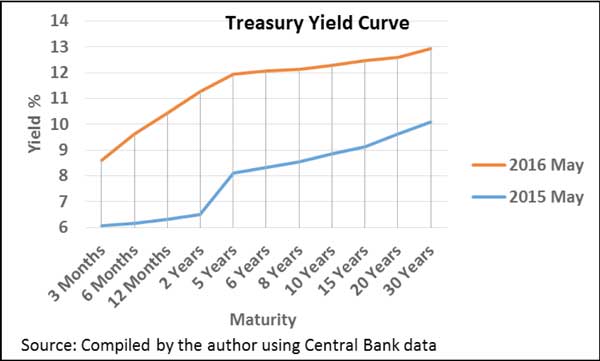

The monetary tightening and the large borrowing requirements of the government have pushed up the rates of Treasury Bills and Bonds in recent months. As shown in the chart, the treasury yield curve, which shows the yield rates of government securities against different maturity periods in the secondary market, shifted upwards in May 2016 compared with the yields prevailed a year ago. At the shorter end, the 3-month Treasury Bill rate rose to 8.60 percent in end-May 2016from 6.06 percent a year ago. The 10-year Treasury Bond rate was up from 8.86 percent to 12.29 percent.

The yield curves depicted in the Chart can be considered normal as theyslope upwards reflecting higher Term Premiums (spread between long- and short-term yields) for long-term bonds. The recent yield curve has a steeper slope up to 5-year maturity reflecting expectations of higher yieldsin the medium term. The flattening of this curve beyond 5 years indicates lower inflationary expectations for the long run.

Constraints in mopping up liquidity

The Central Bank’s decision to increase the policy rates and SRR signaled its intention to end the long phase of declining interest rates which were at record lows fueling excess liquidity. In spite of the monetary tightening; the excess liquidity in the market still remains high. According to the Central Bank’s latest monetary policy review, the expansion of monetary and credit aggregates is expected to moderate only from the second quarter onwards due to transmission lags.

In conclusion, it should be emphasized that the space available to the Central Bank to adopt a restrictive monetary policy stance towards mitigating demand pressures is severely constrained by the excessive borrowings of the government making the adjustment process much more tedious.

(Prof. Sirimevan Colombage, an economist, academic and former senior central banker, can be reached at [email protected])

10 Jan 2025 1 hours ago

10 Jan 2025 2 hours ago

10 Jan 2025 4 hours ago

10 Jan 2025 4 hours ago

10 Jan 2025 4 hours ago