24 Mar 2017 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Today, the United Nations celebrates the International Tuberculosis Day under the theme ‘Unite to end TB: Leave no one behind’. This is a World Health Organisation’s (WHO) End TB Strategy, which calls for a 90 percent reduction in tuberculosis (TB) deaths and an 80 percent reduction in the TB incidence rate by 2030. The focus this year is to address issues relating to stigma, discrimination, marginalization and access to care.

Today, the United Nations celebrates the International Tuberculosis Day under the theme ‘Unite to end TB: Leave no one behind’. This is a World Health Organisation’s (WHO) End TB Strategy, which calls for a 90 percent reduction in tuberculosis (TB) deaths and an 80 percent reduction in the TB incidence rate by 2030. The focus this year is to address issues relating to stigma, discrimination, marginalization and access to care.

TB is one of the major public health threats, with 10.4 million people contracting the disease globally in 2015, of which 1.8 million died. Most of these cases were reported from India which accounted for a 34 percent increase from 2013.

Despite medical advances to cure TB, formidable challenges continue to prevail. These include fragile health systems, the co-epidemics with HIV, diabetes, tobacco use and perhaps most importantly, human resource and financial constraints.

According to the Global Tuberculosis Report, low and middle-income countries rely on international donors for 90 percent of financing on national programmes. These countries incurred a deficit of US $ 2 billion of the US $ 8.3 billion required in 2016. The report further predicts that this annual gap will widen to US $ 6 billion in 2020, if funding does not increase. Apart from this, Multi Drug Resistance Tuberculosis (MDR-TB) is also a contributory challenge. Overall, measures and research to combat the problem of TB remain underfunded.

This article aims to outline the burden of TB in Sri Lanka and highlights the institutional challenges in TB control limiting access to care and proposes recommendations to overcome these discussed challenges in accordance with this year’s focus mentioned above.

Burden of TB in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka is considered a low-burden TB country although in the recent past the reported TB cases have been on the rise. Given that the disease is airborne and easily transmitted through an infected person, poverty, poor living conditions and increased use of tobacco expedites the occurrence and transmission. The recent influx of migrants from China and India is considered contributory factor towards the increased incidents of the disease.

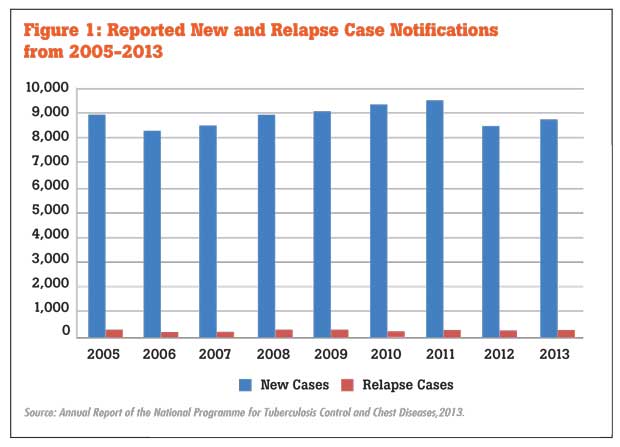

According to the latest data published by the National Programme for Tuberculosis Control and Chest Diseases (NPTCCD) and as depicted in Figure 1, it is evident that the incidence of the rate of TB in 2013 was 44.1 per 100,000 population compared to 42.5 per 100,000 population in 2006. Despite external funding received by the Global Fund for AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (GFATM) and heightened awareness campaigns to promote knowledge and improve access to medication among vulnerable populations by the Ceylon National Association for the Prevention of Tuberculosis, the incidence of the disease continues to escalate.

The government has also taken measures to increase the price of cigarettes by 90 percent in addition to the legal obligation of an 80 percent pictorial warning on the package and a recent proposition to ban the selling of individual cigarettes with the intend of reducing the risk factors associated with contracting TB and other non-communicable diseases. Regardless of these efforts, inefficiencies in the design and implementation of TB prevention and control strategies continue to prevail.

Treatment outcomes

According to the National Strategic Plan for Tuberculosis Control 2015-2020, Sri Lanka has successfully maintained a high treatment rate for TB with the highest rate of 87.1 percent in 2011 coupled with a significant decrease in failure to follow up from 13.8 percent in 2000 to 3.5 percent in 2010. However, the report further highlights that as of recently, there has been a notable increase in those failing to continue treatment from 3.7 percent in 2011 to 4.6 percent in 2012 and 4.8 percent in 2013. These statistics are noteworthy and a serious cause for concern since they are severe lapses in the control of TB care. Substandard in-patient treatment facilities at district hospitals and deficiencies in trained human resources for TB care are factors inhibiting the control of the disease.

Challenges

Given that the incidence of the disease is relatively low in Sri Lanka, the extent of discrimination and stigma associated with the disease is comparatively less compared to India, China and other South Asian countries. A slowdown in the reported TB cases in 2012, as depicted in Figure 1, was not due to a sharp decrease in the total TB cases but rather due to programmatic errors at primary and regional hospitals. Centralized treatment at the district chest clinics, limited use of private providers of Directly Observed Treatment Short course (DOTS) and an absence of a centralized system of registering patients and initiating treatment at this clinic inhibits access to care.

Due to these inefficiencies at peripheral hospitals, TB most often remains undetected in some patients or detected at a later stage of the disease where the medication fails to respond to the bacteria. Others discontinue the medication prescribed and opt for traditional methods of healing due to the transportation costs and other associated personal costs involved in travelling to these clinics/hospitals. All these factors curtail access to TB care.

Way forward

Since Sri Lanka is not a high-burden TB country as its neighbour, India, ending the disease is not a mammoth task. This requires a multidimensional approach where political will and commitment play a central role. Given that TB stems from diverse factors, collaboration and coordination among several government agencies, civil society and private sector is essential to effectively control the disease. Initiating mobile clinics to alleviate the barriers involved in access to care and introducing a family health worker to monitor the progress of TB patients will help ease the issues relating to lost follow up and access

to care.

In addition, given that Sri Lanka has implemented several national policy programmes and secured funding through the GFATM, these funds could be effectively utilized by enhancing the present institutional arrangements to control the spread of the disease. However, in reality the extent to which these stakeholders work in unity to control the spread of this disease and alleviate bottlenecks to improve access to care to end TB remains to be seen.

(Yolanthika Ellepola is a Research Assistant at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). To view this article online and to share your comments, visit the IPS Blog ‘Talking Econsomics’ - http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/)

09 Jan 2025 1 hours ago

09 Jan 2025 2 hours ago

09 Jan 2025 2 hours ago

09 Jan 2025 2 hours ago

09 Jan 2025 2 hours ago