23 Nov 2016 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The term ‘knowledge economy’ is a buzz word used more often in political platforms here nowadays without realizing what it really means. Almost every new development project, be it a mega city project or a power generation project, is launched in the name of knowledge economy to gain political mileage.

The term ‘knowledge economy’ is a buzz word used more often in political platforms here nowadays without realizing what it really means. Almost every new development project, be it a mega city project or a power generation project, is launched in the name of knowledge economy to gain political mileage.

The success of the ongoing mega projects earmarked for the so-called transition towards the knowledge economy heavily depends on the country’s ability to attract foreign direct investment (FDI). Given the precarious macroeconomic instability, institutional failures and many other structural constraints, Sri Lanka has a poor track record over decades with regard to FDI inflows.

Whilst the government’s flagship project Megapolis is reported to envisage massive foreign investment amounting to US $ 44 billion over five years (nearly US $ 9 billion per year), the actual FDI inflows during the first seven months of this year amounted to only US $ 336 million, reflecting a 37 percent downfall from the corresponding period of 2015. So, the maximum amount of FDI that could be expected for this year would be only around US $ 600 million vis-à-vis the projected inflows running into multi-billions a year.

What is knowledge economy?

A knowledge economy is all about creating, disseminating and using knowledge to accelerate economic growth and development. It consists of individuals, companies and sectors that create, develop and commercialize innovative products and export them across the world. It is, therefore, a myth to create a knowledge-based economy just by spending massive amounts of capital for mega infrastructure projects, as we experience now.

Historically, knowledge has always been at the centre of a country’s development process. The rapid progress in creating and disseminating knowledge through fast-developing information and communication technology (ICT) in recent times makes knowledge even more important as an input for accelerating economic growth. A successful knowledge economy is characterized by close links with science and technology and high priority placed on innovation for economic growth as well as for export competitiveness. Research and development (R&D) is a key driver of a knowledge economy.

Two years ago, when there was hardly any policy focus on the notion of knowledge economy in this country, I highlighted the way out to overcome the constraints that we face in transforming Sri Lanka into a knowledge-driven economy at a public lecture delivered at the National Science Foundation. As Sri Lanka has continuously relied on labour-intensive products, she has failed to graduate to the knowledge-based product phase as in the case of East Asian economies. Accelerating economic growth through knowledge-based human capital is the way to rescue the country from what is known as the ‘middle-income trap’, I emphasized in my lecture with supporting data. The then minister in charge of the subject of technology and research, who was in the audience, got inspired by this analysis and expressed his interest in pursuing an innovation-based growth strategy. Our subsequent discussions culminated with the preparation of the first-ever ten-year R&D investment plan for Sri Lanka, which was launched in 2014 enabling to obtain annual budgetary allocations for the purpose.

Using knowledge economy term for political survival

As time goes by, the term knowledge economy has become indispensable for almost every project that the government launches without making much sense, of course. A major objective of the Megapolis project plan launched early this year is said “to optimally harness the benefits of knowledge-based innovation-driven global economic environment characterized by such developments as the new industrial revolution and emergence of smart cities”. The Energy Plan for Sri Lanka presented at an international symposium last year too was related to the knowledge economy.

Nonetheless, the way these infrastructure-based projects lead to create a knowledge economy is not elaborated in any of these mega plans.

Sri Lanka’s potential for a knowledge economy remote

Although knowledge economy is frequently highlighted as the panacea for all ills (‘kokatath thailaya’ in Sinhala) by many political leaders in recent times, the question is whether Sri Lanka has the necessary background to transform itself into a knowledge-based economy. The answer lies on the existence of the preconditions needed for such transformation, which include a conducive economic and institutional regime, modern education system and human resources, advanced innovations and information technology.

Sri Lanka has made very little progress in developing most of the above-mentioned characteristics to enable her transition towards a knowledge economy, whereas the fast-growing Asian countries such as Japan, South Korea, China, Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand have performed much better. Weak economic management, coupled with institutional failures, have restrained gross domestic product (GDP) growth in Sri Lanka. The country’s outmoded education system is not geared to produce the necessary human resources for a knowledge-driven economy.

It has been difficult to retain the talented scientists (produced at the expense of public funds) within the country due to factors such as low remunerations and the lack of opportunities for scientific research. The country does not have a conducive innovation environment, which would have led to acquire international patent rights or to generate new products. Information technology, particularly in the software field, is yet to be developed to reach international standards.

Macroeconomic instability precarious

The prolonged macroeconomic instability has always been a major roadblock to FDI inflows to Sri Lanka. The country suffers from persistent deficits in the government budget and the balance of payments (BoP). The entire government revenue, which is highly dependent on indirect taxes, is hardly sufficient to meet the ever increasing debt service payments and therefore, debt rollover is the norm of the day. The outstanding government debt has gone up to 77 percent of GDP as of today from 69 percent of GDP in 2012. The foreign exchange front is equally fragile. The country heavily depends on the low value added and low-tech garment industry, which is fast losing export competitiveness due to cost escalation, low productivity, labour unrest and emerging foreign competitors. The country’s total export earnings are sufficient to finance only a little over 50 percent of import outlays. If not for the worker remittances, which is equivalent to three fourths of the trade deficit, the country would have faced a severe BoP crisis long ago.

Credit ratings downgraded

It is doubtful whether the country can attract the expected huge foreign investments for the mega projects in the context of the weak macroeconomic outlook, which is unlikely to be rectified in the foreseeable future. The potential to finance these projects through foreign borrowings is also extremely limited as the country already faces severe debt sustainability risks. The government’s outstanding external debt, including the government-guaranteed loans, is estimated to be around US $ 30 billion. The country’s total external debt is around US $ 45 billion, which is equivalent to as much as 57 percent of GDP. Against this backdrop, Sri Lanka’s credit rating has been downgraded to negative levels recently by two major global credit rating agencies (Fitch and Moody’s) indicating significantly high credit risks. This has adverse implications not only for foreign borrowings but also for FDIs.

Technological progress lacking

Having gone through the factor-driven phase, Sri Lanka needs to move to efficiency and innovation-driven growth phases so as to accelerate economic growth. This is not happening even now despite the politicians’ rhetoric on a knowledge economy. As noted above, the export sector has been continuing to rely on primary type of industries, mainly on the apparel industry. Apart from the policy drawbacks, this reflects the lack of innovative capabilities as well as poor commitment on the part of export-oriented companies to diversify their industrial structure with high-tech products. Foreign investors do not show much interest in setting up such sophisticated industries. In contrast, many fast-growing East Asian countries shifted to high-tech products since the 1970s when they lost comparative advantage in low-tech products such as garments.

Such product shift has not materialized in Sri Lanka due to inadequate technological progress. In the circumstances, high-tech exports account for only 0.6 percent of total manufactured exports in Sri Lanka compared with the corresponding ratios of 29 percent in Malaysia, 23 percent in South Korea, 24 percent in China, 15 percent in Japan and 5 percent in India.

Given the severe technology and innovation drawbacks, escaping the middle-income trap is not an easy task for Sri Lanka. It requires an entirely new growth model. The old-styled manufacturing industries dependent on cheap labour and foreign capital would not be sufficient to accelerate income growth. Labour and capital have to be used more productively and in this context, creativity and innovation are critical. A new modus operandi of production process is needed. The local companies must invest heavily in R&D to innovate high-tech products with their own brand names, instead of merely assembling foreign products using imported technology and foreign capital.

Such knowledge-led growth process cannot be expected from the ongoing mega projects which are to be driven by physical capital inputs rather than knowledge inputs.

SL’s knowledge economy ranking unimpressive

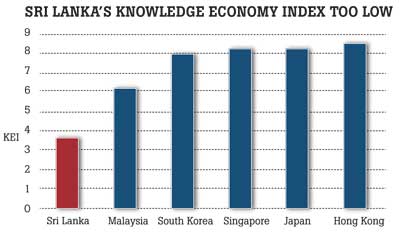

A country’s position with regard to knowledge advancement could be gauged by the knowledge indices compiled by the World Bank. There are two types of knowledge indices: (a) Knowledge Index (KI), which is a composite of three sub-indices covering education, innovation and ICT, and (b) Knowledge Economy Index (KEI), which combines KI and the sub-index for economic and institution regime encompassing tariff and non-tariff barriers, regulatory quality and rule of law. Sri Lanka’s position in the country ranking of knowledge economy is not very satisfactory. She is placed at the 101st position out of 142 countries in the ranking for the year 2012 for which the latest data are available.

In the performance score schedule ranging from 0 (=lowest) to 10 (=highest), the KEI for Sri Lanka is only 3.63 as against very high scores recorded for fast-growing East Asian countries (see the Figure). This indicates that Sri Lanka has to take huge strides to evolve a modern knowledge-based economy.

Mega projects alone insufficient for knowledge economy

Investment in the ongoing mega projects alone is insufficient to shift the country towards a knowledge economy. Other prerequisites should also be in place for the purpose. Human capital, rather than the physical infrastructure is the foundation of a knowledge economy. Economic stability – low inflation, fiscal consolidation, low public debt and strong foreign exchange position – should be sustained by robust macroeconomic policies. Business environment should be conducive to efficient creation, dissemination and use of the existing knowledge.

In this regard, ensuring business confidence through corruption-free political and administrative systems, rule of law, intellectual property rights and good governance are crucial. These factors are essential particularly to attract FDI, which is vital in the transition towards a knowledge-based economy.

In the absence of those prerequisites in the Sri Lankan context, it is miraculous to anticipate a knowledge-driven economy merely by investing heavily in mega projects filled with concrete structures. The future foreign exchange earnings and government revenue to be generated from these foreign-funded ventures are not clear. Revenue generation for the government coffers cannot be expected much from the upcoming Port City project as it has been granted generous 25-year tax holidays. Hence, the emerging debt commitments of such mammoth projects will have to be met by raising indirect taxes further overburdening the ordinary masses. Anticipating a dramatic transition to the knowledge-driven economy without taking into account these somewhat bitter ground realities is undoubtedly a pipe dream.

(Prof. SirimevanColombage, an economist, academic and former central banker can be contacted at [email protected])

10 Jan 2025 10 minute ago

10 Jan 2025 15 minute ago

10 Jan 2025 44 minute ago

10 Jan 2025 1 hours ago

10 Jan 2025 1 hours ago