26 Jul 2017 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

In my previous article of ‘Is Loolkandura or Rotschild first tea estate’, which appeared in Daily Mirror of June 7, 2017, I focused attention to this very important aspect of who planted the first tea plant and gave enough evidence to prove that it took place in 1841 and not in 1867.

In my previous article of ‘Is Loolkandura or Rotschild first tea estate’, which appeared in Daily Mirror of June 7, 2017, I focused attention to this very important aspect of who planted the first tea plant and gave enough evidence to prove that it took place in 1841 and not in 1867.

Ceylon received its first tea seed at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Peradeniya, in 1839, when a consignment was sent from India by Dr. Nathaniel Wallich, who was the superintendent of the Botanical Gardens in Calcutta. This first importation of Assam seed had been collected from tracts of indigenous tea plants growing in thick jungles in the Muttack region of upper Assam in Northeast India.

In 1841, the government received another 200 plants. These plants were sent to Nuwara Eliya for planting. These originals, now deeply rooted in our soil, are reported to be still very much alive on Neasby, now a division of Mahagastota Estate. A further two consignments of plants were obtained from China and Assam between 1841 and 1842. Those from China were planted on Rotschiled Estate, Pussellawa and the Assam variety on Penyland Estate, Dolosbage.

However, it was in early 1841, the nephew of Nathan Mayer Rothschild, Maurice (Born Maritz) De Worms, who went on a voyage to China and brought back a number of cuttings. They were China jat and were duly planted on Rothschild.

In 1867, just two years before the arrival of wind-born spores of H. Vastatrix, coffee planter James Taylor put out 19 acres of tea on Looleconera Estate. This may be the first tea to be planted on a commercial scale in Ceylon. However, the first export of Ceylon Tea, 23 lbs, was in 1873.

By the time the Worms brothers, Maurice and Gabriel, had already turned the shoots into drinkable tea with the assistance of a Chinese tea maker and had sent samples to Worms brothers’ friends in England. It was found to be excellent. According to The Times, the Worms brothers are regarded as the pioneers, if not, the founding fathers of the Ceylon Tea trade.

Poor quality of decision-making

Plantations before the nationalisation were best managed agricultural entities with a world-class accounting system. However, with the failed regime of nationalisation from 1975 to 1992, most of these plantations were re-privatised in 1992 and they were making a loss of approximately Rs.400 million a month.

Following the privatisation of plantations in 1992, the Government of Sri Lanka established the Plantation Management Monitoring Division (PMMD) under the Plantation Industries Ministry to monitor and evaluate the performance of the regional plantation companies (RPCs); needless to mention that it remains a toothless tiger to date. However, no worthwhile monitoring or evaluation took place even though the PMMD and Plantation Industries Ministry had many senior ex-planters in employment.

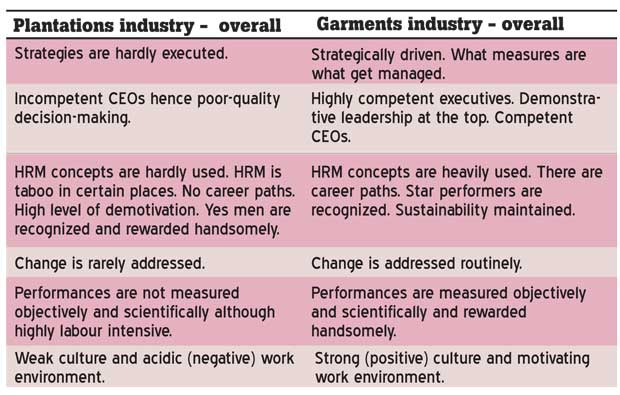

The garment industry that was started during the period of President Premadasa has now overtaken the plantations industry in terms of business performance and growth. When comparing the two industries, the prominent differences are stated in the Table.

The business performance of most RPCs today stands for living proof for what are shown in the Table in brief. These RPCs qualify for world best case studies on mismanagement. We suggest that either the World Bank or universities may document the shocking revelations on unthinkable scale of abuse and corruption in certain RPCs over a period of 24 years since 1993. Who are responsible for these lapses, asset stripping and day light robberies?

In actual fact, the re-privatisations in 1992 were a case of old wine in new bottles. During the period, these plantations were managed by Europeans; the corporate decision-making process (body) was not in Sri Lanka but in London. It consisted of different types of professionals such as economists, accountants, marketers, personnel managers, soil scientists, engineers, IT professionals, medical doctors, agronomists, managers, etc.

This is a point worth considering and understanding as a major cause for the utter failure since nationalisation up to the present times covers almost 42 years. What had been in Sri Lanka during the times of the British was a small office in Colombo, called ‘Agency House’, manned by a senior planter, mostly of European origin, and superintendents to manage their estates.

Do we have a product?

Any product has a life cycle and the same concept applies to tea. Diversification is a process that takes place when the product reaches the stage of ‘declination’ in the market with the passing of time. Although it happened to the production of tea a few decades ago, the decision makers have been ignorant due to reasons best known to the industry.

To begin with, one can question if the bulk tea sold through auctions count as a product or raw-material. Raw materials are used in the primary stages or rather the manufacturing process of a good. Raw materials are often referred to as commodities, which are bought and sold at commodity exchanges around the world.

Black tea was treated as a raw material and therefore remained over a century in the commodity market without being developed into a product. Had this been done, a reasonable price would have been created and product positioning would have occurred in the minds of the consumer globally.

Attributes of a product include size, colour, functionality, components and features that affect the product’s appeal or acceptance in the market. If the products were developed out of tea, then there won’t be a need for an auction system as the products are marketed and not auctioned. Products also need to be developed and diversified at the appropriate time. Therefore, the decision makers and the government must be conscious enough to refrain from spending millions on marketing raw materials or commodities overseas based on false propaganda of ‘tea promotion’.

The fundamental mistake with the tea industry of Sri Lanka is the lack of a product and the product mix that should be appealing to different market segments, whilst giving the producer a sizable margin to maintain the economic viability of the industry. Putting the same black tea that was produced by the planters and workers some hundreds of years ago into a nicely decorated packaging cannot be considered proper value addition. It could be a very primary way of doing things.

Black tea remains a commodity or a raw material now. There are a number of products that can be made out of this raw material that the customers are looking for. We are unaware if there is a single food scientist that is assigned with this task with a team of research and development (R&D) scientists.

There are many beverages we are aware of that need no marketing strategies to sell and get sold like hot cakes because the consumer feels value for money in those beverages. Not only we don’t have a right product getting sold like those beverages but we also link the virgin beauty of our own sisters and daughters to the product with the intention of marketing our tea. Wrong action could always end up with wrong results. Multinational corporations (MNCs) use young groups of both male and female to capture markets for beverages.

If celebration is a must, then we should use this opportunity to launch a basket of new products out of tea, which will boost revenue so that the industry will be benefitted and grow.

We are confused as to what is there to celebrate other than a single event of the history falsely articulated.

Sir Thomas Lipton, the son of poor Irish immigrants, a genius, was not in the area of growing tea but rather in the marketing and distribution of the final product. Even Merrill J. Fernando embarked on his journey in tea nearly five decades ago. He sought to bring quality Ceylon Tea to the consumers. Dilmah introduced some fine brand product tea to the pioneering concept of tea, ‘picked, perfected and packed’ at origin.

The decision makers of the tea industry here did not only avoid making a sellable product but were equally guilty of generating low revenue as a consequence of remaining in the commodity market.

The low competency in the top management therefore, had paid a supreme price costing a national economy and a wonderful industry. In the meantime, we salute those who made the maximum use of the existing body of knowledge on developing a product mix and marketing those products globally.

The few who did well and the majority who failed are the partners of the same industry here, which helps the observers to separate the men from boys. Therefore, it is clear that the incompetence in management and negligence to develop a sellable product together laid the foundation for the downfall of this industry. Is that what we are in for celebrations?

The public must be happy to note that at least one political party is now loud and clear about the character of their candidates that will be on the race at the next forthcoming Provincial Council elections. Similarly, the Planters’ Association is of high importance to the RPCs. It’s the responsibility of the National Intelligence Bureau to advise the minister concerned on the quality of material managing similar organisations.

‘Dirt collecting dirt’ is a phenomenon we have heard from our childhood. If it is allowed to happen, especially at national level, no one will be able to put a stop on corruption and abuse of power.

Also, national reconciliation will only be meaningful if we walk the talk. The national policy on languages is on snail speed in the industry. The ministry must take the lead and insist that any communication in the industry must be in all three languages. We believe that both the above have led to forgetting the planters, staff and workers at unnecessary celebrations on account of a falsified story of 150 years of tea here.

Forgetting human resources is part of the acidic culture of the RPC-managed plantations industry. Abuse of power and engaging in corrupt practices at very high positions is somewhat the latest additions. The industry is being killed. Who will come forward to rescue the industry?

Anyone interested in verifying the accuracy of these matters can summon stakeholder consultation through the establishment of a commission appointed within the constitutional framework of Sri Lanka. Careful investigations into the information that are bound to surface in numbers will point their fingers on ulterior and sinister motives of some of these companies manned by veterans. Executives at that age are usually risk averse and will not even attempt to initiate change or to face new challenges effectively. They will satisfy their masters at whatever the cost though some of those methods may be lowering the human dignity.

We are still not too late to start a new journey with the end in mind. The tea industry of Sri Lanka is in a calamitous and precautions must be taken before its utter downfall. Taking all that is stated above into consideration, let us work to help this industry grow to be bigger and better. The time has come for a new state of mind and some positive thinking because even at this latter stage, a turnaround is still very much a possibility.

Let’s not give up now. It is still within reach of US $ 10 billion by 2020. That is the challenge. The CEOs of the RPCs who manage their plantations strategically must be admired publicly and felicitated in a most fitting manner and in the process and the rest must be encouraged to follow suit.

We do strongly believe that the plantations industry in general and the tea industry in particular can be turned around with the right policies put in place by the government and the owners of RPCs, replacing their top executives with that of highly competent in management and in human resource management concepts in particular.

(Lalin I. de Silva is an ex-senior planter and can be reached via [email protected])

06 Jan 2025 49 minute ago

06 Jan 2025 2 hours ago

06 Jan 2025 2 hours ago

06 Jan 2025 2 hours ago

06 Jan 2025 2 hours ago