09 Aug 2017 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The objective of a free trade agreement (FTA) is not to bring about a balance in trade but to work out a ‘win-win’ situation for both producers and consumers in the FTA member countries. In doing so, there can be instances where the trade deficit increases for one partner.

The objective of a free trade agreement (FTA) is not to bring about a balance in trade but to work out a ‘win-win’ situation for both producers and consumers in the FTA member countries. In doing so, there can be instances where the trade deficit increases for one partner.

For instance, the inflow of necessary consumer goods, machinery and spare parts for industrial activity and intermediate goods like textiles and oil, to one trading partner can be huge, while the supply capacity of the same trading nation may be limited and cannot immediately expand its exports to match the import flow.

In the case of India-Sri Lanka Free Trade Agreement (ISFTA), Sri Lanka has been able to reap benefits from the FTA, contrary to the general belief, if one looks beyond Sri Lanka’s trade deficit vis-à-vis India.

Usage of preferential tariffs in FTA

If one looks at the composition of imports from India to Sri Lanka, the bulk of it comes mainly to fulfil consumer needs, like vehicles, pharmaceuticals, sugar, etc. Some other imports are intermediate imports for the industry, like textiles, vehicle parts and oil. For example, Sri Lanka annually imports close to US $ 60 million worth of yarn and US $ 300 million of fabric from India as inputs in the apparel industry. All these items constitute, on average, nearly 80 percent of Sri Lankan imports from India and they are imported outside the provisions of the ISFTA.

In other words, these items are subject to normal customs duties and they do not benefit from any tariff concessions. Hence, they enter the Sri Lankan market because they are the most competitive input source and provide value for money for intermediate and/or final products for local producers and consumers.

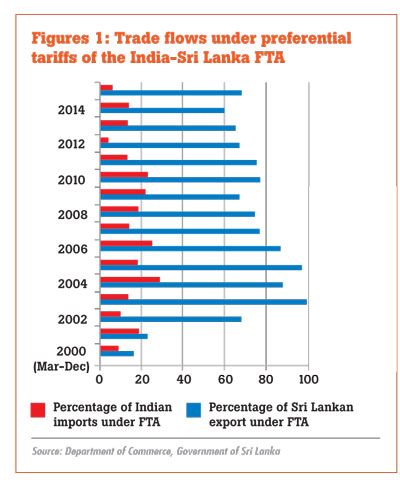

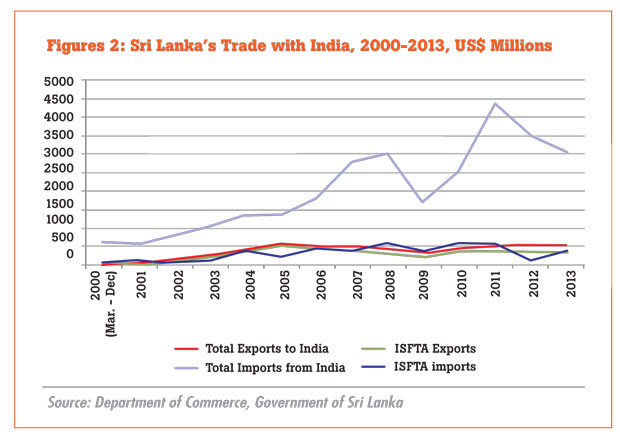

Contrary to imports, nearly 70 percent of Sri Lanka’s exports go to India using the FTA provisions. Thus, these exports benefit from the zero tariffs granted by India. Clearly, Sri Lanka has been using the FTA more than India (Figure 1). Plotting the goods traded between the two countries under the FTA shows that there is hardly any deficit between the two countries (Figure 2). In fact, Sri Lanka has enjoyed a surplus on trade conducted under the bilateral FTA with India in six of the 16 years since the FTA came into force.

Trade balance and export basket

On the basis of the above data, one can convincingly argue that the trade balance between the two countries would have been more in favour of India if the FTA was not in existence. These facts demonstrate that it is misleading and incorrect to claim that India has benefited much more from the FTA, merely by citing the size of the overall bilateral trade deficit.

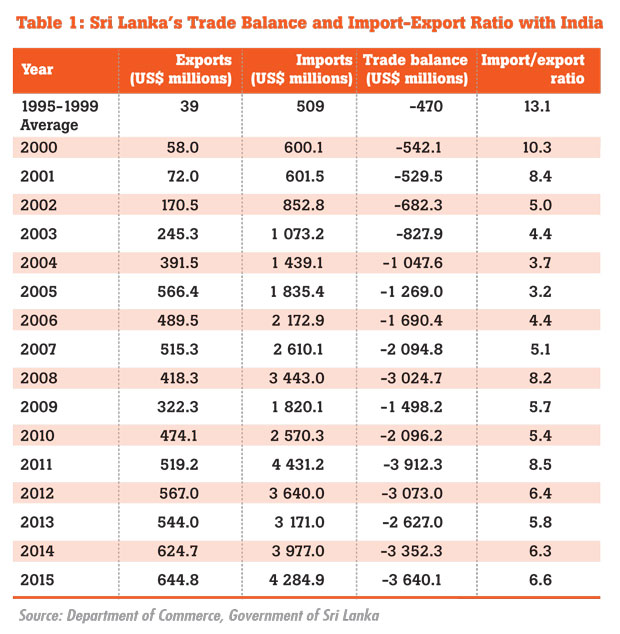

If we look at the import/export ratio between the two countries, we can clearly see that the ratio has declined from 10.3 in 2000 to 6.6 in 2015 (reaching a peak favourable ratio of 3.2 in 2005, as shown in Table 1). This indicates that the Sri Lankan exports to India have grown faster than Indian exports to Sri Lanka (Table 1).

While India has been the largest source of imports for Sri Lanka (even before the FTA) for many years, India has acquired the position of being the third largest destination for Sri Lankan exports – a rank achieved through the benefit of the tariff preferences in the FTA. In that sense, India is the most balanced trading partner for Sri Lanka – ranking high in both imports and exports of Sri Lanka.

If one looks at the Sri Lankan export basket destined for India before the FTA, which was dominated by agricultural products such as cloves, peppers, areca nuts, dried fruits, nutmeg, etc. exports have now (after the FTA) become more diversified. It includes boats/ships, wires and cables, glass and glassware, apparel, woven fabric, etc. In 2013, the largest Sri Lankan export to India was boats and ships.

Critics of the India-Sri Lanka FTA often state that Sri Lanka does not export items to India similar to those it exports to the European Union or United States (apparel, leather products, etc.). The point to note here is that the export basket may vary from country to country but what eventually matters is the overall exports. There was a time when copper was the largest export to India (in 2003), likewise vanaspathi (in 2005) and areca nuts (in 2014).

These fluctuations do occur in FTAs, especially when shrewd entrepreneurs exploit the loopholes in such agreements. The case of vanaspathi (a type of processed vegetable oil) highlights the volatility that can sometimes be brought about by distortionary protectionist measures in place.

Indian investors began to process vanaspathi in Sri Lanka for export to India due to the low preferential tariff rates that were available to Sri Lankan exporters, contributing to the surge in exports between 2003 and 2006. This eventually caused an outcry in India, leading to an imposition of quotas on vanaspathi imports from Sri Lanka. This eventual imposition of quotas negatively affected close to 4,000 jobs in Sri Lanka.

Having said that, the available data shows that, while Sri Lanka exported 505 product items to India before the FTA in 1999, the product items exported increased to 1062 by 2005 and to 2100 product items by 2012, after the implementation of the FTA. This quadrupling of the product items during 1999-2012 provides further evidence for Sri Lanka diversifying its export basket to India after the FTA came into operation in 2000.

Moving forward

Sri Lanka should not lament about the trade deficit or the export basket but move forward with the rest of the world to gain maximum benefits from FTAs. The India-Sri Lanka FTA has certainly worked in favour of Sri Lanka but more work needs to be done to broaden and deepen it to reap the maximum benefits from it for Sri Lanka in an equitable manner.

One of the key areas currently being addressed are non-tariff barriers in the Indian market. Non-tariff measures are not barriers to all Sri Lankan exports but for some of them, like marble, maggie boards and perishable food items. These barriers have been clearly identified through stakeholder consultation by the Commerce Department.

Trade facilitation shortcomings were identified by an extensive survey in the report prepared by the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). All such findings have now been submitted to the Indian Commerce Department for early resolution. The Government of Sri Lanka is attaching high priority to resolving these issues expeditiously.

What needs to be noted is that even with some non-tariff barriers in the Indian market, Sri Lankan exports have made a mark in that market. Based on this, one can argue that a deeper economic engagement with India can generate even more positive and beneficial outcomes, provided the negotiations ensure that Sri Lanka’s interests are pursued vigorously. That is precisely what is being attempted through the proposal of the Economic and Technology Cooperation Agreement (ETCA). It will lay the foundation for Sri Lankan exports and investments to benefit more from the rapidly growing Indian market.

(The late Dr. Saman Kelegama was Executive Director, Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). Dr. Kelegama passed away on June 23, 2017 in Bangkok. This blog is an abridged version of the Asia-Pacific Research and Training Network on Trade (ARTNeT) Policy Brief (No. 50, July 2017), which was submitted prior to his passing. It was subsequently prepared by Panit Buranawijarn, a Research Assistant at the ARTNeT secretariat and published posthumously. The Policy Brief can be access at: http://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/polibrief50.pdf)

06 Jan 2025 1 hours ago

06 Jan 2025 2 hours ago

06 Jan 2025 2 hours ago

06 Jan 2025 2 hours ago

06 Jan 2025 2 hours ago