12 Oct 2017 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The rice bowl of Sri Lanka is experiencing the worst drought of the past 40 years. Expectations of the Agriculture Department are that this year would yield the lowest paddy harvest in over 10 years. If one were to journey through the Polonnaruwa District—one of the major paddy supplying districts and the political citadel of President Maithripala Sirisena—the picture painted would be sprawling paddy fields, with most abandoned to the weeds.

The rice bowl of Sri Lanka is experiencing the worst drought of the past 40 years. Expectations of the Agriculture Department are that this year would yield the lowest paddy harvest in over 10 years. If one were to journey through the Polonnaruwa District—one of the major paddy supplying districts and the political citadel of President Maithripala Sirisena—the picture painted would be sprawling paddy fields, with most abandoned to the weeds.

Amidst the bone-dry conditions, some farmers are finding solace, or more accurately, are thriving by planting a cash crop, which has been facing crackdowns from the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the Sri Lankan government for its negative implications on health. Swathes of nicotiana tabacum, commonly known as the tobacco plant, can be found planted intermittently among the sparsely cultivated paddy fields.

“This crop doesn’t need that much water. Also, elephants attack often. So the tobacco plantations are the only thing which keeps the elephants away. If there were any other crops, the elephants would have come in and destroyed everything,” said A.M. Munasinghe Banda, a barn owner from Elahera in Polonnaruwa, whose farms lay just a brisk walk away for the elephants of the Wasgamuwa National Park.

Tobacco requires just one-seventh of the water and much less effort in land preparation compared to paddy, thus becoming popular among the barn owners and farmers during the drier months in the Yala agricultural season, which runs approximately from April till August or September, during which Ceylon Tobacco Company PLC (CTC) sources 80 percent of its tobacco.

The sporadic showers, which were experienced in the region over the past few weeks, in fact worried the farmers that the tobacco leaves would droop and rot with an oversupply of water.

Is the give as good as the take?

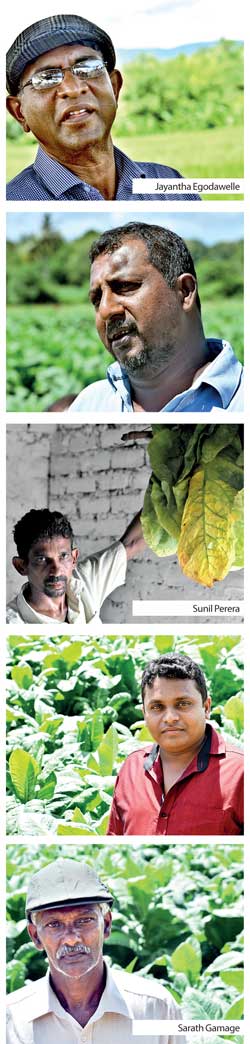

According to All-Island Barn Owners’ Association President Jayantha Egodawelle, there are currently over 20,000 barn owners—more powerful tobacco farmers who also own tobacco leaf curing barns, but also are, for the most part, paddy farmers during the Maha season—in Sri Lanka.

Egodawelle, himself a second-generation barn owner and a tobacco farmer, who had also had a fairly successful public service career, gets chauffeured around in a double cab, perhaps indicating the level of prosperity tobacco farming brings to its farmers.

The income derived during the handful of months in the Yala season turns the farmers into millionaires, allowing them to breathe easy during the rain-heavy, paddy-cultivation-friendly Maha season.

“During the Yala season, a hectare of tobacco yields Rs.300,000 in profits. I have five hectares under cultivation, so that’s Rs.1.5 million in profits. If I planted paddy, I wouldn’t have gotten even Rs.200,000 in profits,” Munasinghe Banda, one of the handful of barn owners CTC introduced to the visiting journalists, said.

With these profits, the farmers have experienced improved lifestyles.

“We have built houses and bought vehicles. Our villages depend a lot on tobacco farming and we contribute a lot when there are social and religious events in the village,” said P.G. Dissanayake, a third generation barn owner who has been cultivating tobacco for over 16 years to compensate for the fickle fortunes of paddy cultivation.

Sunil Perera—another barn owner from a village not too far from Elahera, who at that particular moment seemed to be blissfully unaware of the friendly jests thrown his way with reference to the flamboyant front man of the band The Gypsies—too has thrived with the fortunes of tobacco farming.

“I’ve managed to build a house for myself and houses for my children. Now I’m investing in acquiring more land for cultivation,” he said.

This is not to say that a considerable number of tobacco farmers don’t squander away their fortunes with gambling and alcoholism, which many agree is prevalent in these areas.

On hindsight, it strikes that CTC would have been more morally responsible in communicating the economic and social effects of tobacco farming to regional economies if it had introduced a bigger cross section of lower-rung farmers and support workers—many of whom work under the prosperous barn owners, at times just for a day’s meal.

However, these barn owners too understand that the crop, which so generously bestows wealth upon them, is not so kind towards their compatriots.

“We aren’t saying that smoking cigarettes is good. We know that the ‘bulath vita’ (Paan) is harmful, but we chew it. Similarly, the person wanting to smoking will smoke,” Dissanayake said.

While the role of the government in determining the freedoms of man is always debated, the Sri Lankan government has followed on the footsteps of its peers by banning advertisements of tobacco products and introducing regulations to the packaging of cigarettes.

Constantly being reminded of the fact that 75 percent of Sri Lankan deaths are caused by non-communicable diseases of which a major cause is smoking, the government now appears to be taking a more aggressive policy towards tobacco, by announcing its intention to ban tobacco cultivation by 2020, a measure which is even more drastic compared to the WHO’s aim of eradicating tobacco smoking by 2030.

However, these tobacco farmers are not convinced of the altruism of the government’s policy. ‘Threats and lies’ appear to be the message they are receiving from the government.

Threats and lies?

President Sirisena and Health Minister Rajitha Senaratne last year proposed to ban the cultivation of tobacco locally by the year 2020, as part of the president’s plans to limit the consumption of tobacco and alcohol in the country.

The efforts of limiting consumption so far have only resulted in consumers moving towards illegal and illicit alternatives, much like how children secretly engage in activities after parents forbid them. In fact, according to CTC Operations Director Dr. Rukshan Gunatilaka, the annual steep increases in taxes on cigarettes have resulted in smuggled cigarettes and less regulated and more hazardous beedi catching up to the expensive, locally manufactured cigarettes in market share.

According to him, the land extent used to cultivate low-quality tobacco for beedi, mainly in the Northern Province, is almost as much as the 2,500 hectares of land under cultivation by the farmers who partner with CTC in the Polonnaruwa, Kurunegala, Matale, Kandy, Badulla, Monaragala and Nuwara Eliya Districts.

It is the farmers supplying to the regulated industry—with well-documented contracts and records of tobacco cultivation, standardization, investment and higher incomes—who are facing the greatest uncertainty with the government’s intended policy direction.

“If the ban happens, we will have immense losses. He (President Sirisena) is from the next village but I don’t know what he will do. If he bans, then a lot of barn owners will be in trouble. We will have to find some other employment,” Perera said.

Dissanayake pointed out that the barn owners have invested heavily in infrastructure such as barns for curing the tobacco leaves, storage facilities and mechanization processes—which have been developed by CTC in reply to skyrocketing labour costs and the challenge in attracting labour to agriculture—will require compensation if their livelihoods are taken away.

“I don’t think any other type of farmer has invested so much in their farming practices,” he said.

Indeed, whenever there is a paddy glut, one could surely find miles and miles of queues, where paddy farmers, without such infrastructure, spend days attempting to sell their produce to the millers and wholesalers—a monopoly held by President Sirisena’s family—and at times end up selling paddy to these middlemen even below the cost of production.

In contrast, in tobacco farming, CTC enters into a purchase agreement with tobacco farmers even before the planting season, to set the price and volume of tobacco to be purchased following a harvest, ensuring an equilibrium price and quantity in the market. CTC also provides fertilizer, plants and other agricultural support on a cost-recovery basis, in addition to technical expertise to ensure a sustainable supply of tobacco at high yields per hectare.

“That’s a big strength. We know even before planting, that we can have a certain amount of profit in our hand by the end of the season,” said Noel Nawaratne, a 33-year-old barn owner, who has flourished with tobacco farming after running into stiff challenges in the field of academics.

With the government’s threat of banning tobacco farming by 2020, the farmers are afraid of being left high and dry, unable to continue their lifestyles or pay back loans undertaken to invest in their farming businesses.

“I’ve got some bank loans. I’ve bought two tractors under lease. If this ban happens, I will default on my loans,” said Sarath Gamage, another barn owner from Elahera.

The government would have to take this issue under serious consideration, given the increasing number of reports this year on farmers committing suicide due to their inability to repay loans.

The proposed ban is adding up to the distrust already built up amongst the farmers on the ill-intentions of the government. According to CTC Agronomist/Research Manager Rasika Abeysekera, public officials occasionally raid tobacco farms and uproot plants without any legal backing, requiring CTC to at times intervene on behalf of the farmers.

Dissanayake said that everyone should be vigilant about the government’s true intentions on the ban.

“Everyone needs a clear view of the situation. Although the tobacco cultivation will be banned, cigarettes won’t be banned. Then what’s the point of this policy? If they banned the cigarette, we won’t be able to sell our produce and we will stop farming. But the government is ready to ban tobacco cultivation without banning the cigarette,” he said, apparently convinced that the ban is a conspiracy for political stooges force the importation of tobacco leaf, in order to earn fat commissions at separate junctures of the supply chain.

Such sentiments are not unwarranted, given the multiple ‘anomalies’ witnessed in procurement—especially in the energy sector—and in treasury bonds, which appear to have put hefty profits and commissions in the pockets of certain individuals. Nawaratne too expressed sentiments identical to Dissanayake.

“If the government is willing to stop cigarette smoking, we are ready to stop tobacco cultivation. They want us to stop production, but then people will import and make commissions. Then what happens to us? Will we get justice? Will we be paid compensation for all the investment and hard work we’ve put in?” he questioned.

According to Dr. Gunatilaka, CTC is prepared to import tobacco from its associate companies in the British American Tobacco group across the world, although the additional cost of sourcing from foreign markets would add Rs.2 billion more to the cost of CTC. Although the company will be adversely affected, it would be a long stretch to call the ban on local sourcing fatal for CTC, which made Rs.12.56 billion in net profits last year compared to Rs.10.63 billion in 2015.

No solution

Since the farmers would be the most affected by the ban on local cultivation, they last year requested the government to point them towards an alternative crop, which could provide similar levels of income to tobacco.

Egodawelle pointed out that reintroducing paddy would be counterproductive, given that over 7,500 hectares of paddy would have to be cultivated to bring the same level of prosperity to these farmers compared to 2,500 hectares of tobacco.

“Then we get hundreds of tonnes of paddy. Because there was no rain this season to give a good paddy harvest, there may be a demand for such paddy supply now, but during a normal season, this would mean an addition of hundreds of tonnes of paddy to the market. Then what happens to the price of a kilogramme of paddy a farmer sells? Secondly, with the current weather anomalies, there’s not enough water for even three months of drinking. So, can we provide water for 7,500 hectares more of paddy cultivation? So, we ask the government this,” he said.

The government instead directed the farmers to experiment with other crops, none of which have brought in the income the farmers expected.

“We did Bombay onions, pumpkin and papaya but we didn’t get a fair price. Out of the earnings from these crops, the profit is around Rs.50,000-60,000. At times, we can’t even break even,” Dissanayake said.

He said that he managed to survive that year due to also planting tobacco to a limited extent.

“But in the end, because I had my tobacco plantation, I managed to break even. Otherwise I would have become a victim. So, tobacco plantation is good for us. There’s not much soil erosion and we use very little weed and herb killers. So, the health of the soil is maintained,” he added.

Nawaratne, who had experimented with corn, pepper and onions, noted how CTC officials visit and provide such technical expertise for tobacco plantations within one hour of farmers requesting help, but for other crops, when a farmer calls for help from the government, it takes around two to three weeks for a public official to visit the farms.

Dissanayake meanwhile said that with the threat of elephant attacks, most of the crops the government recommends are not viable in the area and promises of providing better yielding seeds for alternative crops have also not materialized.

“The government lies and says that they will give us this and that. They don’t even give us the water. If they want to introduce an alternative crop, give us at least two to three years, where tobacco farming will be limited to 50 percent of the current capacity, with experimentation in the other 50 percent, at least to see if the alternative will make up for the revenue from the discontinuation of tobacco,” he said.

04 Jan 2025 4 hours ago

04 Jan 2025 4 hours ago

04 Jan 2025 5 hours ago

04 Jan 2025 6 hours ago

04 Jan 2025 6 hours ago