31 May 2016 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

For well over a decade BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China) nations, an acronym invented by Goldman Sach’s Jim O’Neill, have been synonymous with global economic growth.

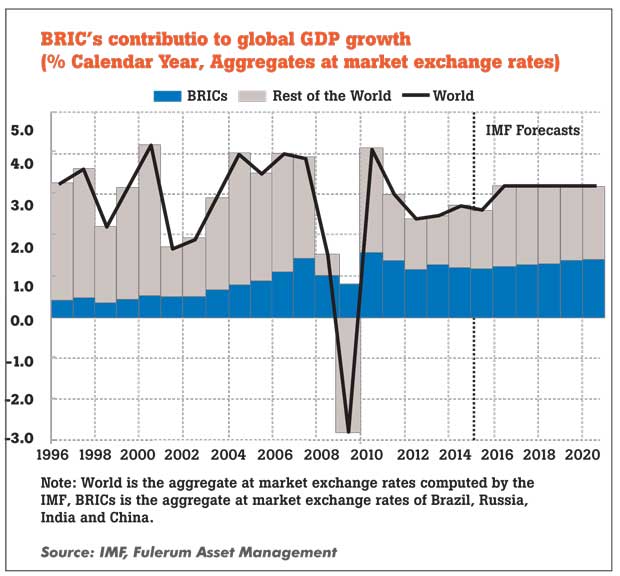

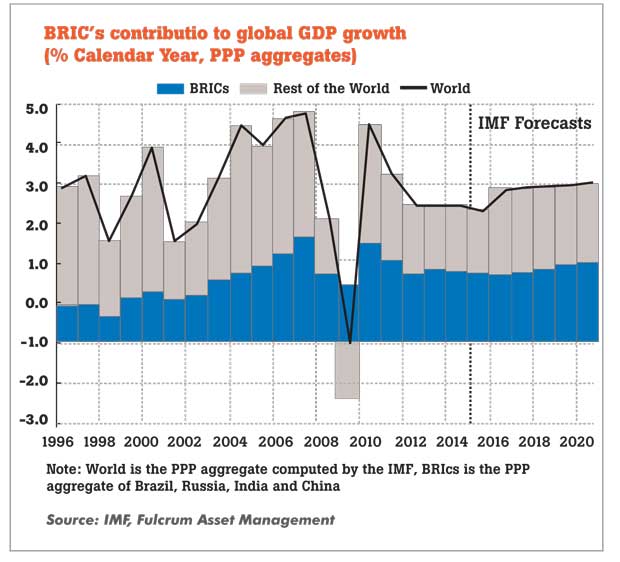

These four economies had little in common, except that they had the scale and growth potential to transform the global GDP growth rates since early 2000s. The graphs below show that the BRICs were negligible contributors to global growth in the 1990s, but by 2010 they were contributing between one third and one half of all global growth, depending on whether the data are measured in market exchange rates or PPP rates.

Since the 2008 financial crisis, global growth has trended well below 4 percent (measured at market exchange rates) and is expected to stay in this trajectory over the next several years as per International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecasts. In the face of weaker global demand and the decline of commodity prices, wheels have started to come off the BRICS (South Africa was added to the list later) growth wagon. China’s growth is decelerating, Brazil and Russia have been in recession for the last three years and growth in South Africa remains sluggish at best. India is the sole BRICS nation that is continuing to march forward with above-trend growth, thanks to long overdue structural and regulatory reforms, and initiatives such as ‘make in India’.

In this article we take a closer look at three fundamental factors that are shaping global growth today: the deceleration of China, monetary policy normalization in the US and lower commodity prices.

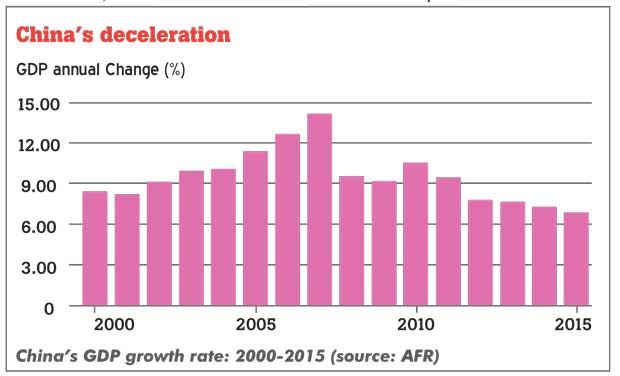

China’s deceleration

Slower economic growth, a depreciating currency, and a gyrating stock market are making global political and business headlines, giving rise to the notion that China’s economic miracle is ending. Even at subdued growth rates of 6 percent-7 percent, China’s growth is still the envy of most countries and would still generate more additional output than a 14 percent growth rate achieved back in 2007. While the law of larger numbers predict China’s growth rates of the past three decades, which averaged 10 percent a year, is untenable and would eventually wane, it is the structural headwinds facing the Chinese economy that worry most analysts.

The tri-factors of labour, capital and productivity fueled superlative growth rates of China for many years. However, China’s working-age population peaked in 2012 and average wages have risen 12 percent per annum since 2001, making once widely available cheap labour much more expensive. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) inflows are also on the decline, falling below 3 percent of GDP and shifting from labour-intensive manufacturing into high-tech manufacturing and the service industry. China’s technological gap with rich countries is also narrower than in the past, implying that productivity growth will be lower too.

To add to its woes, China’s credit-binge that allowed it to power the economy through the global financial crisis is beginning to bite back. Total debt (including government, household and corporate) has ballooned to a staggering 250 percent of GDP, up 100 percentage points since 2008. Most worryingly, much of the credit flowed to property developers and today China’s inventory of unsold homes sits at a record high. The real-estate sector, which previously accounted for some 15 percent of economic growth, could face outright contraction. The decline in construction along with heavy industries have depressed demand for oil, iron ore and other commodities, dragging down growth in commodity exporting economies such as Australia, Brazil and Russia.

The communist government has reacted to the slowing economy with a raft of measures, beginning with a cut in interest rates last November. After two years of tightening credit conditions, regulators loosened access to credit last summer and devalued the currency. China’s president Xi Jinping, has continued to spread the gospel of the ‘new normal’, i.e. less emphasis on growth but faster structural reform that promotes innovation and competitiveness.

Despite all the turmoil, Chinese consumers’ confidence has been surprisingly resilient as salaries have continued to rise and unemployment has stayed low. Right now, China is transitioning from broad-based market growth to an economy where consumers are becoming more selective about where they spend their money, shifting from products to services and from mass to premium segments. At a macro-economic level, decades of infrastructure and export-led double digit growth is now replaced by single digit growth driven by domestic consumption and innovation that improves China’s global competitiveness.

Monetary normalization by the Federal Reserve

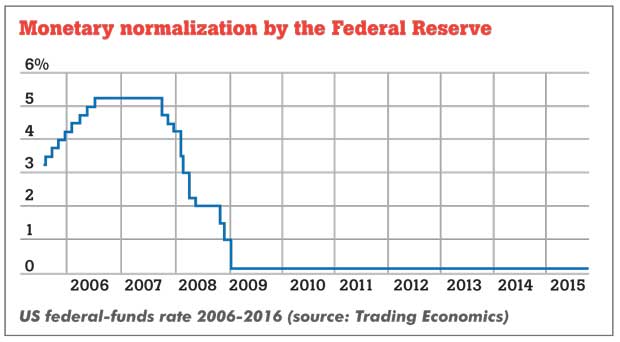

In December 2015, the Federal Reserve increased its benchmark federal-funds rate by 25 basis points, after holding it at near zero levels for seven years. This signaled the end of an extraordinary period of market intervention adopted by the Fed in order to support the recovery of the US economy from the worst financial crisis and recession since the Great Depression.

In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, several central banks started pumping money into their economies to stimulate growth, otherwise known as Quantitative Easing (QE). Between 2008 and 2015, the US Federal Reserve in total bought bonds worth more than US$3.7 trillion. The UK created £375bn (US$ 550bn) of new money via its QE programme between 2009 and 2012. This helped to increases the overall amount of funds in the financial system and encouraged financial institutions to lend more at historically low interest rates. The Eurozone began its programme of QE much later, in January 2015, and has so far pumped in US $ 600bn of extra money. Originally the programme was set to run until September 2016, but due to continued weakness of Eurozone economies it has now been extended until at least March 2017.

The Fed’s benchmark funds rate was kept at 0.25 percent since December 2008. This helped the US economy to recover and keep the value of the US$ artificially low. However, now with the US economy growing at a steady pace (recording a GDP growth rate of above 2 percent since 2012), and with unemployment set to fall below 5 percent for the first time since 2008, the Fed is embarking on a path of ‘monetary normalization’.

This so called ‘Yelen-effect’, named after the Fed chairperson Janet Yellen, will have a major impact on global growth during 2016. From a more ‘hawkish outlook’ on Fed rates at the beginning of the year, where some experts predicted as many as four rate hikes during the course of the year, the Fed’s economic language has turned more ‘dovish’ warning against rapid rate hikes that could damage the fragile growth at home as well as abroad. Nonetheless, with an upward trajectory set for Fed rates the USD is set to strengthen against other global currencies affecting capital flows to the rest of the world.

Low commodity prices

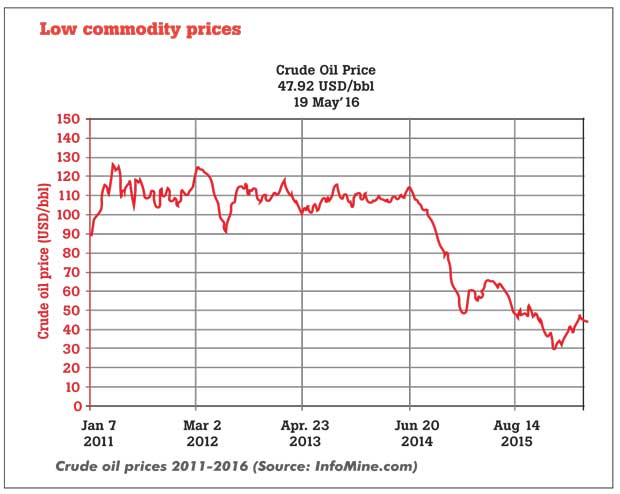

The low commodity prices we are seeing currently are being driven by a simple supply-demand equation. The rapid economic growth over the past two decades, led by the BRICS economies, gave rise to a ‘commodity boom’. In order to respond to the increasing demand, commodity producers expanded their capacity at a rate greater than the demand. As the global economy slows down, commodity producers find themselves in a ‘commodity glut’ that is driving down the prices to record lows with experts predicting a ‘Lower for Longer’ era for commodities.

For example, the price of the most headline grabbing commodity, oil, has plummeted a staggering 70 percent since June 2014. Such a steep drop in oil prices was last seen during the 2008 financial crisis. However, this time around the prices have fallen more sharply and are expected to remain well below the US$75 per barrel mark for much longer.

So what are the main factors contributing to these record low oil prices?

On the demand side, the weakness of European economies, and deceleration of emerging markets are major factors. More energy-efficient cars and alternative fuels such as solar and wind power are also driving down the global demand for oil.

On the supply side several factors are contributing to an ‘oil glut’:

nThe United States’ domestic production has nearly doubled over the last several years, as hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, is being used to extract oil and gas from large shale deposits. Saudi Arabian, Nigerian, and Algerian oil that once was sold in the United States is suddenly competing in Asian markets, and the producers are being forced to drop their prices.

nDespite falling oil prices, members of OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) have continued to pump oil into the global markets in the hope of driving out US shale oil producers, further increasing the supply.

nCanadian and Iraqi oil production and exports are rising year after year. Even the Russians, despite their economic woes at home, manage to keep pumping. The return of Iran into the international fold will add further volume to global oil production. Lower oil prices are good news for commodity consuming economies such as India, China and Japan, while it is paralyzing to ‘petrostate’ economies such as Venezuela, Brazil and Russia.

The ‘Capex commodities’ such as steel, copper, cement etc. are primarily used for infrastructure development. As China’s property boom turns to bust, and large post-recession infrastructure investments in developed markets slow down, prices of steel and copper have taken a heavy hit. Iron ore prices have nearly halved from its peak of early 2013 whilst copper prices have suffered a similar fate. Economies such as Australia (where one third of export revenues come from China) that benefited from the commodity-boom are also struggling due to crashing iron ore and coal prices.

Impact on Sri Lankan economy

So how do these factors affect the Sri Lankan economy? Our economy has always been hyper-sensitive to oil prices and the US$ exchange rates. As an oil consuming nation, lower oil prices are welcome news for the economy and offers much needed respite at a time a when the trade deficit is widening and foreign reserves are dwindling.

On the flip side, the low oil prices have put a dent in the revenues of oil producing Gulf economies. This has had a knock-on effect on Sri Lanka’s foreign remittances, the largest foreign exchange earner accounting for 9% of the GDP. In a recent report the rating agency Fitch, warned that Sri Lanka along with Pakistan and Bangladesh were among South Asian economies most vulnerable to a slowdown in the foreign remittance disruption from the Gulf states. The Central Bank in its 2015 annual report also noted a sharp decline of 12.4 percent in the total number of departures for foreign employment compared to previous year, sighting escalated geo-political tensions and slowing economies of the Middle-East.

Monetary normalization by the Fed will inevitably strengthen the US$ against the Sri Lankan Rupee, making our imports more expensive, and putting further pressure on a beleaguered Rupee. It will also slowdown other economies around the world, threatening our export revenues. China’s deceleration is not expected to create a major impact, as it is not yet a major export destination for Sri Lanka. In fact we should benefit as Chinese investors continue to look towards neighbouring, high growth markets to offset slower growth at home. In the recent past, Chinese tourist arrivals to Sri Lanka have experienced double digit growth, but we may see a decline in this as Chinese consumers tighten their purse strings.

Concluding remarks

Double-digit growth is most certainly a relic of China’s past as the economy transitions from infrastructure and export led run-away growth to more moderated growth driven by domestic consumption and innovation.

Unprecedented, near-zero US Fed rates are set to rise as the US economy wakes up from its post-financial crisis hibernation, driving up the value of US$ and affecting capital flows to rest of the global markets. Commodity prices are set to experience a ‘lower for longer’ period as nearly two decades of demand growth, primarily fueled by emerging markets, is replaced with a demand contraction

and a supply excess resulting in a ’commodity glut’.

All these factors combined with the continued weakness in the Eurozone is expected slowdown global growth during 2016 and beyond.

(The writer is attached to Stax Inc, a global strategy consultancy serving private equity firms and corporations across a broad range of industries. The firm partners with clients to provide data-driven, actionable insights designed to help management grow organically, enhance profits, increase value, and make better M&A decisions. Founded in 1994, Stax has offices in Boston, Chicago, New York, Singapore and Sri Lanka. For more information, please visit www.stax.com.)

10 Jan 2025 13 minute ago

10 Jan 2025 15 minute ago

10 Jan 2025 20 minute ago

10 Jan 2025 2 hours ago

10 Jan 2025 3 hours ago