19 May 2017 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

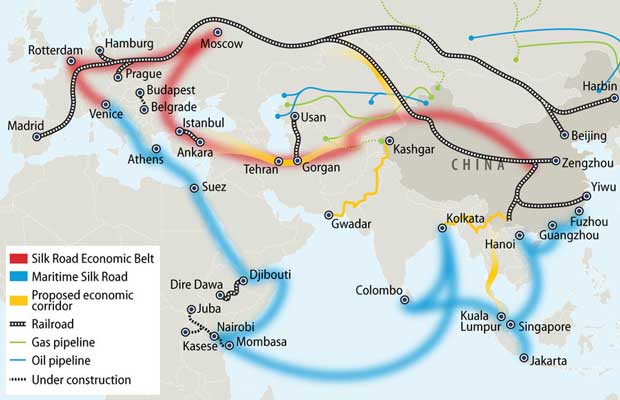

High-speed railways in Indonesia and Hungary. Deep-water ports in Pakistan and Sri Lanka. Gas pipelines across central Asia. All are part of what is arguably the largest overseas development drive ever launched by a single nation.

High-speed railways in Indonesia and Hungary. Deep-water ports in Pakistan and Sri Lanka. Gas pipelines across central Asia. All are part of what is arguably the largest overseas development drive ever launched by a single nation.

Even the Marshall Plan, America’s post-war reconstruction effort in Europe, pales in comparison to the more than US $ 900 billion China has pledged for the construction of infrastructure projects in more than 60 countries as part of its ‘One Belt, One Road’ initiative.

Chinese President Xi Jinping outlined his vision for this modern-day Silk Road during a two-day forum in Beijing that ended Monday. While the initiative is still in its early stages, it comes at a critical moment in Asia. The developing countries in the region need to invest some US $ 1.7 trillion per year on infrastructure to maintain growth, tackle poverty and fight climate change, according to the Asian Development Bank. Meanwhile, the United States seems poised to reverse the Obama administration’s plans for a ‘pivot to Asia’.

The Belt and Road Initiative gives China the opportunity to create a political and economic network based on its own rules, with the ambitious goal of establishing what Chinese state-run media have dubbed “globalization 2.0.” Xi used the forum this week to present himself as one of its leaders – and, in stark contrast to US President Trump, as an advocate for free trade.

“We should embrace the outside world with an open mind, uphold the multilateral trading regime, advance the building of free trade areas and promote liberalization and facilitation of trade and investment,” Xi said Sunday in his opening speech.

Yet, his call for governments to pursue “greater openness” and “reject protectionism” has raised eyebrows. The trading partners, who complain that China is the most-closed major economy, question whether the Belt and Road initiative will let foreign companies in on the action. And despite Beijing’s decades-long support for non-interference – not meddling in other countries’ domestic affairs – foreign policy analysts ask if its growing economic leadership will give rise to more political ambitions, too.

Staking its claim

Speaking to an audience that included the leaders of 29 countries – including Russian President Vladimir Putin and Central Asian autocrats – Xi insisted on Sunday that China had “no desire to impose our will on others”. He said economic globalization should be “open, inclusive, balanced and beneficial to all”.

Xi pledged an additional US $ 14.5 billion to the Silk Road Fund set up in 2014 to finance infrastructure projects and US $ 8.7 billion in aid to developing countries and international organisations. He also announced that two government-run banks would distribute loans of US $ 55 billion to support Belt and Road projects.

China’s leader didn’t mention Trump by name, but the implicit message was clear: If an inward-looking United States is going to focus on “America first”, China is ready with a new economic order for the world to follow. “The situation in the US and in the EU with Brexit has created an international policy vacuum,” says Peter Cai, a fellow at the Lowy Institute in Sydney and author of a recent report on the Belt and Road initiative. “China has been emboldened to step into the vacuum and stake its claim as a global economic leader.”

Cai says China has greatly expanded the scope of the initiative since Xi announced its launch four years ago. What was once largely focused on infrastructure in Asia now extends all the way to central Europe, as well as Africa and the Middle East. In a sign of its growing reach, delegates from more than 100 countries and the leaders of international organisations including the United Nations and World Bank attended the forum in Beijing.

“Britain led globalization for more than 200 years and the US led it for more than 100 years,” says Huiyao Wang, President of the Centre for China and Globalization in Beijing. “Now it needs new energy.”

That energy is something China is eager to provide, especially after Trump abandoned the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the Obama administration’s signature trade agreement, on his first full weekday in office. With American economic influence in the Asia-Pacific region likely to wane, China wants to take its place as it looks to open new markets for Chinese goods and reassert itself as Asia’s leading power. “Xi wants to make China great on the international stage,” Tom Miller, author of ‘China’s Asian Dream: Empire Building Along the New Silk Road’, said at a book talk in Beijing last month. “He wants China to predominate in the East, much as the US does in the West.”

Who owns the road?

Critics say China is trying to rewrite the rules on global trade and security in pursuit of its own economic and geopolitical interests.

They warn that Beijing’s proven willingness to work with authoritarian regimes could undermine human rights and environmental standards in the developing world. Meanwhile, economists have raised concerns that the massive infrastructure projects, if poorly conceived or negotiated, could leave poor countries with unsustainable levels of debt.

Supporters of the initiative, such as Zhang Yansheng, Chief Research Fellow at the China Centre for International Economic Exchanges in Beijing, say China’s aim is to supplement the existing global governance and economic systems – not replace them.

“‘One Belt, One Road’ is a way to help rebalance the world economy. It’s about how to reduce the gap between rich and poor,” Zhang says. “The image China wants to send to the world is that ‘One Belt, One Road’ does not only belong to China, it belongs to the world.”

The parts of the world that the initiative targets are fraught with risk. Cai of the Lowy Institute says nearly two-thirds of the countries that have accepted the Belt and Road projects have credit ratings below investment grade. In nations such as Pakistan, rampant corruption and security threats also present significant challenges.

And how far China is willing to go to uphold its commitment to non-interference, the unconditional respect for state sovereignty, will surely be tested as its economic influence over other countries grows. What could China do to protect the US $ 57-billion economic corridor it’s helping to build through Pakistan, where militants have killed 44 Pakistani workers since 2014? What about Beijing’s perceived threat from ethnic Uighurs from the western region of Xinjiang who are suspected of fighting with militant groups in the Middle East and accused of killing Chinese diplomats in central Asia?

“China will have a considerable amount of economic leverage as these projects get built,” Cai says. “The temptation to use that economic leverage will always be there, but only time will tell if China decides to use it in pursuit of other interests.”

(Courtesy http://www.csmonitor.com)

08 Jan 2025 15 minute ago

08 Jan 2025 1 hours ago

08 Jan 2025 3 hours ago

08 Jan 2025 4 hours ago