25 Aug 2016 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Nearly three decades since the adoption and ratification of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), women’s economic empowerment is gaining increasing policy priority as a fundamental strategy to achieve inclusive growth. In contrast to previous schools of thought, development policy today is informed by the idea that women constitute the largest untapped potential for economic development and harnessing that potential is the single most impactful step to reach all other development goals.

While the nexus between women’s empowerment and development is well established, there has been little focus on understanding the tools for empowerment; particularly, the potential for information and communications technology (ICT) to facilitate women’s economic empowerment and stimulate broader growth. Despite extensive empirical evidence of the propensity for ICT to advance development, women’s access to technology remains significantly low with 25 percent fewer women having access to Internet when compared to men in the developing world. These trends hold true in the Sri Lankan context as well, with women’s participation in the information economy lagging significantly behind that of men. As Sri Lanka continues to make ICT a policy priority in its development agenda, it must consider the consequences of excluding women and girls from the information revolution and work to bridge fundamental disparities in access to technology.

Sri Lanka’s gender digital divide: Why don’t women have access to ICT?

Social and cultural factors contribute significantly towards shaping women’s participation in the information economy. Even policy interventions designed to promote inclusiveness among all socioeconomic groups tend to underestimate the gender dimensions of information gatekeeping. While evidence suggests that Internet usage by women is higher in countries that are more gender equal and rank higher on the Human Development Indicators (HDI), Sri Lanka’s progressive ranking has done little to promote women’s access to ICT.

A study conducted by Kottegoda et al (2012) reveals that girls’ use of and participation in rural telecommunication centres is deterred by concerns over safety as well as stigmas attached to ‘mixing with boys’. Despite the seeming inconsequentiality of these factors, these examples highlight the propensity for culture to define women’s relationship to technology.

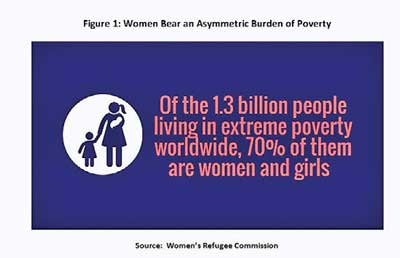

Moreover, poverty is another significant constraint to ICT access. While it is true that this limitation affects both genders, statistics (Figure 1) show how women bear a disproportionate percentage of the burden of global poverty as a direct result of the lack of income, social protections, gender bias and social and cultural influences. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) report on gender dimensions of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in Sri Lanka also reveals a higher incidence of women in new poverty groups.

The feminization of poverty around the world and in Sri Lanka has significant consequences for women because it regulates access to ICT and limits the ability to break the cycle of poverty: If women are more likely to be victims of poverty, they are less likely to own and utilize technologies, which in turn limit their ability to graduate from poverty.

Why ICT matters for women and economic development

Supporting women’s participation in the information economy has direct positive impacts on gender equality as well as economic development in a country. Outlined below are some of the ways in which ICT facilitates the economic empowerment of women and stimulates development.

I. Supporting female entrepreneurs

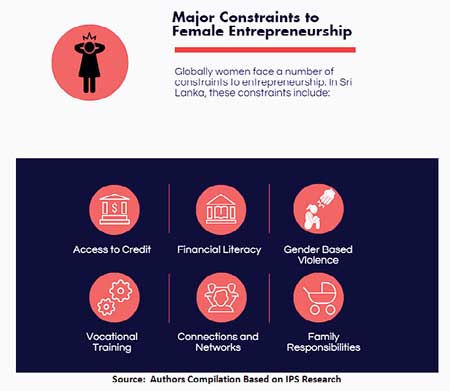

Female entrepreneurs have long been deemed engines of economic development and harnessing their potential is vital to achieving sustainable growth. The rise in the number of female-owned small and medium-scale enterprises (SMEs) has provided Sri Lanka with an unprecedented opportunity to scale-up entrepreneurship among women and increasing access to ICT is key to leverage this potential. ICTs are particularly well poised to help overcome barriers that are specific to female entrepreneurs such as lack of access to equity, information and limitations on mobility and time.

Lack of access to capital remains one of the core constraints to female entrepreneurship with women facing barriers in discrimination and implicit gender bias. Although women constitute over 31 percent of SME entrepreneurs in Sri Lanka, they are statistically far less likely to access private equity or venture capital. ICT scan help women bridge these fundamental disparities through crowdfunding platforms such as Crowdfunder, Kickstarter and Indiegogo, which replace traditional means of capital investments and offer women alternate platforms to fundraise.

In fact, research reveals that female entrepreneurs are almost 10 times more successful in raising capital via online platforms than with traditional banks and five times more successful when compared to their venture capital investments. Moreover, ICTs offer female entrepreneur stools to bridge gaps in knowledge and training. The introduction of long-distance learning promoted by e-education initiatives supports women’s continued education by affording them the flexibility to manage work and familial obligations.

II. Advancing female labour force participation

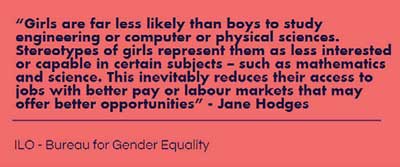

A breakdown of female labour force participation in Sri Lanka shows that out of the ‘total economically active population’ only 34 percent are women. Disaggregated data on women’s participation in industries related to science and technology reveal even lower numbers: the National ICT Workforce Survey of 2013 confirms that women constitute only 29.7 percent of the total ICT sector in the country. An increase in access to ICT and training in IT literacy will provide opportunities for Sri Lankan women to participate in the labour force by opening up sectors of employment (in technical fields) that are traditionally dominated by men. Despite the lack of comprehensive data, evidence suggests that the asymmetrical representation of women in these occupations can be linked to low rates of concentration in technical fields at all levels of education.

Increasing ICT access to girls at a young age should, therefore, be a policy priority when considering gender parity in the information economy. Statistics from Girls Who Code – an organisation providing coding camps to girls in the United States – reveal the extent to which access to IT literacy can boost the female technical workforce: over 90 percent of the girls who participate in their programme went on to major in computer science or a closely related field of study. While initiatives such as Connect to Learn are working to increase IT literacy rates among teenage girls in rural communities in Sri Lanka, these efforts need to be strongly supported at an institutional level by local and national governments.

III. Empowering women to be change agents in economic development

As a result of the pervasiveness and innovation of technology, ICTs are emerging as strategic tools to combat significant challenges to economic development such as poverty, mortality and malnutrition. Mobile technologies, for instance, are revolutionizing healthcare delivery around the world, with organisations such as Dimagi, GiftedMom, MomConnect and MAMA leveraging low-cost SMS-based services to provide timed and targeted antenatal and neonatal information to pregnant women and their caregivers. These initiatives have resulted in significant reductions in maternal and infant mortality in communities that lack access to basic healthcare facilities.

Similar initiatives in Sri Lanka include Mobile for Development – a programme that aims to leverage SMS services to educate 150 women in two rural communities on child care, health, hygiene and financial management. The importance of empowering rural women as economic actors cannot be underscored. As primary decision-makers on health, education, nutrition and education within the family unit, rural women ensure the wellbeing of not only their families but also their entire communities.

The way forward

It is evident that when women have access to ICT tools they are capable of harnessing their economic potential to unleash positive economic outcomes. While anecdotal evidence points to significant gender disparities in access to ICT, the lack of data on IT literacy and access to ICT is a core constraint to understanding the issue. The collection and dissemination of data is, therefore, vital to inform policy making and set policy priorities that are necessary to achieve Sri Lanka’s development goals.

Furthermore, it is important to develop a stronger mandate for gender mainstreaming across all areas of policymaking. In recognizing that women’s access to ICTs is contingent upon the realization of women’s rights more broadly, it is critical to incorporate gender perspectives across a wide range of development policies in order to ensure that women have the opportunity to overcome all factors – psychological, material, skills and usage – that regulate their participation in the information economy. If Sri Lanka is serious about achieving its status as a ‘regional ICT-enabled commercial hub for South Asia’, it must begin this process of mainstreaming soon to ensure that women are not left behind.

(Anarkalee Perera is a Research Assistant at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka)

10 Jan 2025 1 hours ago

10 Jan 2025 2 hours ago

10 Jan 2025 3 hours ago

10 Jan 2025 3 hours ago

10 Jan 2025 3 hours ago