16 Mar 2016 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Often changes in international markets can have a direct, positive or negative impact on a country. Such an impact may be a result of exogenous shocks (climate change), large market failures (e.g. financial crisis, high volatility in world prices), international agreements (e.g. multilateral or regional trade agreements), unilateral policies of large economies (e.g. agricultural domestic support or biofuel mandates).

Often changes in international markets can have a direct, positive or negative impact on a country. Such an impact may be a result of exogenous shocks (climate change), large market failures (e.g. financial crisis, high volatility in world prices), international agreements (e.g. multilateral or regional trade agreements), unilateral policies of large economies (e.g. agricultural domestic support or biofuel mandates).

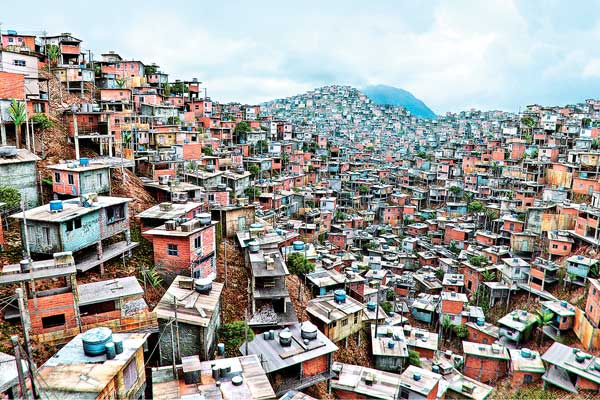

While the effects of these changes vary across countries, depending on their trade specialization, degree of openness and adjustment capacities, the domestic redistributive impact among citizens in a particular country can be quite pronounced. However, there is ample evidence that poverty is not directly the result of a country’s share of trade. Rather, poverty reflects low earning power, poor access to communal resources, poor health and education, powerlessness and vulnerability. It does not matter what causes these features so long as they do not exist, nor what relieves them if they can be relieved.

Trade matters only to the extent that it affects the direct determinants of poverty and that, relative to the whole range of other possible policies it offers as an efficient policy lever for poverty alleviation. Trade liberalization may have adverse consequences for some – including the poor – that should be avoided or managed to the greatest extent possible. However, the general belief is that trade liberalization promotes growth, which in turn, supports poverty alleviation.

In general, only a few people will end up as net losers. Therefore, trade policy should not be closely manipulated with an eye on its direct poverty consequences and impact on employment, but set on a sound basis overall with the recognition that some modification may be inevitable for political and other reasons with poverty being treated by general anti-poverty policies.

Trade barriers

More compelling is the dramatic upturn in gross domestic product (GDP) growth rates in India and China after they turned strongly towards dismantling trade barriers in the early 1990s. In both countries, the decision to reverse protectionist policies was not the only reform undertaken, but it was an important component. In developed countries, trade liberalization, which started earlier in the post-war period, was accompanied by other forms of economic opportunities for example, a return to currency convertibility, resulting in rapid GDP growth.

Moreover, the argument that historical experience supports the case for protectionism is now flawed. The economic historian Douglas Irwin has challenged the argument that nineteenth-century protectionist policy aided the growth of infant industries in the United States - nor should the promoters of free trade worry that trade openness results in no additional growth for some developing countries. Trade is only a facilitating device.

If a country’s infrastructure is bad, or have domestic policies that prevent investors from responding to market opportunities such as licensing restrictions, very little progress can be achieved. Critics of free trade also argue that trade-driven growth benefits only the rich and not the poor. In India, however, after the economic and education reforms nearly 200 million people have come out of poverty. In China, which grew faster, it is estimated that more than 300 million people have moved above the poverty line since the reforms were initiated.

Faster economic growth

Poverty is still the biggest problem in South Asia; large sections of people in South Asia do not even have access to safe drinking water and to basic sanitation services. South Asia is extremely diverse in terms of culture, politics, and religion. Such diversity entails difficulties in promoting regional cooperation. In fact, the speed of regional cooperation in South Asia has been very slow compared to other regions.

There are three important areas, for promoting greater regional trade;

First, is the need for strengthening of mutual surveillance across the region.

Second, countries in the region should share a common view of the future direction of the regional economy and develop concrete policy responses based on their future direction.

Third, participate in global efforts to stabilize the international financial system.

Over the next few decades, South Asia needs to grow their economies at a much faster pace to eradicate poverty. They will need to strengthen and deepen their democracies and ensure the region is stable and secure. But that can only be achieved, if South Asia works together and promote more and more interregional trade because economic stagnation in one part of our region will only dampen prosperity in another.

In addition, South Asia needs to ensure its financial system is stable and easy to access and also foster a political climate that creates confidence in its region. In the final analysis, increased regional co-operation will not only boost trade and welfare and political capital but also prevents internal conflicts from spilling over national borders.

(Dinesh Weerakkody is a thought leader)

26 Nov 2024 45 minute ago

26 Nov 2024 1 hours ago

26 Nov 2024 1 hours ago

26 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

26 Nov 2024 3 hours ago