21 Feb 2017 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

February 20th marked the anniversary of the World Day of Social Justice.

February 20th marked the anniversary of the World Day of Social Justice.

This commitment, made by the UN in 2007, is rooted in the ILO Declaration on Social Justice for a Fair Globalisation and focuses on guaranteeing fair outcomes for all through employment, social protection, social dialogue, and fundamental principles and rights at work.

Unsurprisingly, an important focus of this commitment is the economic empowerment of women and girls. According to the United Nations: “Observance of World Day of Social Justice supports efforts of the international community in poverty eradication, the promotion of full employment and decent work, gender equity and access to social well-being for all”

It is in this context that this article chooses to examine the status of female labour force participation (LFP) in Sri Lanka.In doing so, it recognises the enduring positive impact of female LFP on broader economic outcomes and, more importantly, on poverty alleviation and social protection among women.

Labour force participation, as defined by the ILO, is “a measure of the proportion of a country’s working-age population that engages actively in the labour market, either by working or actively looking for work.” According to 2015 estimates, the rate of labour force participation among women in Sri Lanka is 35.9. This means that a disproportionate majority of women remain outside the labour market, with no access to wages, pensions and other benefits tied to gainful employment.

Pervasive constraints

While evidence points to several pervasive constraints on women’s participation in the labour force– ranging from protectionist legislature to the lack of access to vocational training – it has become increasingly evident that social and culturalfactors play a defining role in determining women’s inclusion in the labour market. These cultural constraints primarily stem from negative attitudes towards women’s work as well as societal perceptionsof women’s roles and responsibilities in the household. These cultural norms, which are often internalised by women, negatively influence a woman’sdecision to pursue gainful employment opportunities and limither occupational choice and earning capacity in the long run. If Sri Lanka is serious about transitioning from its status as a lower-middle income country, it must address these key constraints in order to ensure that women become an engine of sustained economic growth.

Why increasing female LFP important for Sri Lanka?

While female LFP is an important social goal in itself, it is also crucial from an economic growth perspective. Empirical evidence on the negative outcomes of gender asymmetries in the labour market is extensive and underscores the positive nexus between female LFP and economic development.

For instance, studies such as Cuberes and Tiegner (2015) demonstrate the extent to which gender gaps negatively affect per-capita income and productivity; according to their findings, gender inequality creates an average income loss of 16 percent in the short-run and 17.5 percent in the long-run for developing countries.

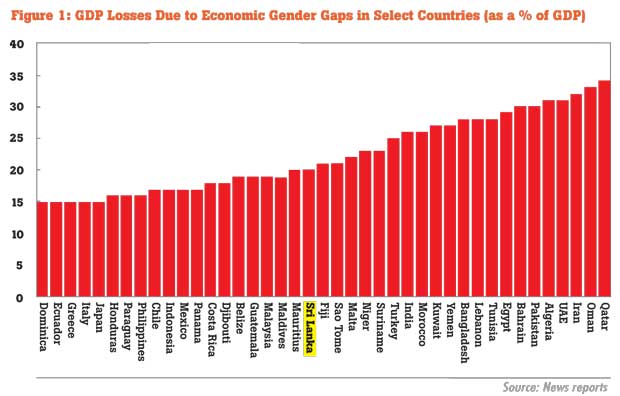

In Asia alone, UNESCAP estimates that restrictions on women’s access to employment opportunities result in a loss of US$42 - US$47 billion per year. Other studies also highlight significant losses to GDP that occur due to gender asymmetries in the labour market; an IMF staff noteestimates an average loss of 20% to the Sri Lankan economy stemming from lower participation rates among women (Figure 1).

Beyond macroeconomic impacts, labour force participation is also fundamentally important for poverty alleviation.

Providing wage employment to poor women, who constitute the majority of those in poverty, is crucial to providinglow-income women with the tools to overcome persistent poverty.

Sociocultural constraints to female LFP

Evidence from studies on female LFP in Sri Lanka revealsthat household income and status of wealth plays a significant role in determining a woman’s decision to seek employment. Studies such as Guntalika (2013) show that receipt of remittances and earnings of male household members deter labour force participation among married women and female heads of household.

While it is hard to locate the precise driving force behind this trend, it is safe to posit that these trends are largely reflective of traditional views onmale and female income earners. Although women are considered to be economic actors, their income is regarded as ‘supplementary’ to that of male income earners who, traditionally, play the role of primary breadwinner. Therefore, women who receive income from other sources such as remittances,or live with the high-earning male family members, do not feel the need to seek gainful employment opportunities in the market.

The study further finds that having children below the age of five is also a significant deterrent to labour force participation. While this trend is also undeniably reflective of pervasive attitude towards women’s roles as mothers and caretakers, it is also indicative of the disproportionate burden of unpaid care work that women continue to shoulder. The opportunity cost that results from cutting back on work hours or dropping out of paid labour force is well documented. Nancy Folbre, a leading economist at the University of Massachusetts calls this opportunity cost the ‘care penalty’and argues: “unpaid work, by definition, carries a pecuniary penalty: one forgoes the potential earnings from working the same hours in a paid job. In addition, because pay is affected by how much job experience one has, women who leave employment to rear children suffer wage penalties for years after they re-enter the job market”

While socio-cultural perceptions and attitudes impact a women’s decisions to enter the labour force, these factors also influence hiring practices. A recent study conducted by the ILO titled Factors Affecting Women’s Labour Force Participation in Sri Lanka (2016) reveals the extent to which socio-cultural norms and perceptions hinder women’s access to employment opportunities. Although the study did not find evidence of overt discrimination, it found that gender stereotyping led to indirect discrimination in the hiring process. For example, Key Person Interviews in the study revealed that managers were more likely to hire men “due to extraneous considerations such as higher probability of women having family responsibilities”.

Policy recommendations and conclusion

While theGovernment of Sri Lanka has recognised the need to address the low rate of participation among women in the country, its focus has not been on addressing these cultural norms and practices that continue to hold women back. If Sri Lanka hopes to tap into the productive potential that women hold to stimulate growth, it must work to change the pervasive perceptions around women’s work. It must also work to develop greater support systems for women who continue to operate within current socio-cultural frameworks.

For example, the state should consider the provision of affordable (perhaps publicly financed) care services that would reduce the burden of unpaid care work on women. This is particularly important in the context of Sri Lanka, where low fertility rates and an increasingly ageing population is likely to increase the dependency burden on women in the future. Introducing day-care options at places of employment is another alternative worth considering.

Similarly, the introduction of flexible work options – such as part-time work and working from home – could also support a woman’s ability to achieve a work-life balance. A survey of more than 1,000 workers in Australia, a country where over a 50 percent of Australian organisations have a workplace flexibility policy in place, revealed that women were 10 percentage points more likely to work flexible or alternate hours.

In addition, 38 percent of women also claimed to be working night-shifts or part-time to juggle professional and personal obligations. It is evident that with the right systems in place, women have the willingness and ability to economically empower themselves.

Finally, Sri Lanka should promote policies that support the more equitable distribution of family responsibilities in the household. For example, the expansion of paternity leave benefits could encourage men to take up greater responsibility in child-careactivities. In addition to sharing the costs of family care, Nancy Folbre argues that the impact of such policies could also have a positive effect on re-engineering gender roles in societyby validating the value of care work. As a result, they could have a large cumulative and ripple effects on society as a whole.

(Anarkalee Perera is a Research Assistant at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka)

09 Jan 2025 47 minute ago

09 Jan 2025 2 hours ago

09 Jan 2025 3 hours ago

09 Jan 2025 3 hours ago

09 Jan 2025 3 hours ago