15 Jan 2018 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

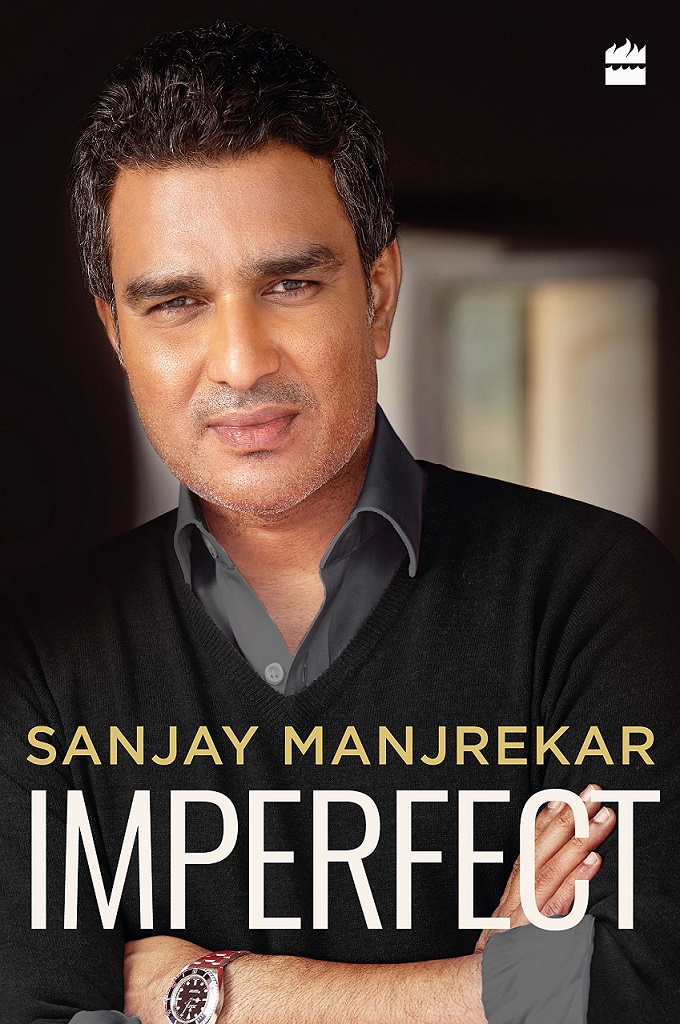

In this except from his book ‘Imperfect’, Sanjay Manjrekar talks about one of India’s most controversial matches ever and debunks some conspiracy theories.

When it was time to turn up for the semi-final, a lot of us had not recovered from the euphoria of the previous game. Ajit Wadekar, our team manager, sensed that.

Wadekar carried an image of a happy-go-lucky character who bumbled his way through life. In reality, I found out he was the exact opposite, especially when in a position of responsibility – be it as the Indian captain or as an employee at the State Bank of India where he rose in the organisation to reach one of the top positions that any Indian Test cricketer held in the corporate world.

There was something about Wadekar. It is no coincidence that the famous 1971 triumphs in the West Indies and England came under him. He was one of those people who felt Indian cricket should be second to none. When he was made India coach, it was surprise for everyone. He had been out of the game for a while, and at first didn’t seem physically ready to go through the rigours that s hands-on coach needs to. After a few days, though, he got himself fit enough to give us a 100 catches a day.

More importantly, Wadekar became the boss of the team. Indian cricket teams are generally run by the captain and one or two seniors. The coach is often like a prop on the stage, happy to keep his job and not rock the boat. Not Wadekar, though. For the first time in my career I knew who was taking important decision and he was happy to accept responsibility for that. He found it hard to defeats on earlier tours, like the one to South Africa in 1992-92. You could see that it hurt him, personally.

Wadekar was the first Indian coach who made sure everybody was making the most of the practice sessions; he didn’t let anyone take it easy for even a minute. For example, after the batsmen had finished their knock in the nets, they were immediately sent to relentless fielding drills: taking catches and attacking the ball when it was hit at you and then trying to hit the stumps directly. He was smart- he knew what Indian cricket lacked and made sure he was going to do something about it.

Importantly, Wadekar knew that the Indian team had the tendency to relax after tasting some success. I remember once when after winning a match, we were having some fun on the flight. That evening in the team meeting at the hotel, he shouted at us unexpectedly, ‘What do you think? You have the tournament or something? What was happening in the flight? What kind of behaviour was that?’

Before the semi-final against Sri Lanka, he sensed something similar and he called for a team meeting. It went on for quote long; Wadekar did most of the talking. Once he was done. Mohammad Azharuddin, the captain, spoke a few words. Although the meeting lasted an hour or so, around fifty minutes were spent on how to contain their openers Romesh Kaluwitharana and Sanath Jayasuriya. The duo had decimated us in a league match earlier in the tournament, chasing down 272 without any fuss. They had reduced Manoj Prabhakar to bowling off-spin, hastening the end of his career.

Imagine our surprise, then, when we got both out in the first over in the semi-final. I caught Kaluwitharana for a golden duck at third man off Srinath, and his new-ball partner Venkatesh Prasad caught Jayasuriya. Now we didn’t know what to do. Like Abhimanyu in Mahabharata, we had trained ourselves to get to the target in the ‘chakravyuh’ but didn’t prepare ourselves about getting out of it.

We relaxed, in a fashion typical of the cricket we played in the ’90s. If you look at our jubilation after getting Kaluwitharana and Jayasuriya out, it was as if we had won the World Cup. We basically took the eye off the ball, and Aravinda de Silva made us pay for it. Sri Lanka ended up scoring 251.

In the chase, Tendulkar and I had a 90-run partnership, and at no point did we think there were nay real demons in the pitch.

Now, a pitch should not change in ten minutes. But that’s what wickets do; a few fell quickly and the demons woke up.

Kumar Dharmsena bowled an off-break to Azhar that pitched outside off and ended with Kaluwitharana down the leg side – he had to collect chest high. It was called wide; I will never forget Dharmsena’s smile – to me it was the smile of the devil, but he had perhaps realised that the match was theirs now; they would go to Lahore for the finals, not India.

Apart from Dharmsena, they had three more spinners – Muttiah Muralitharan, Jayasuriya and de Silva, if needed. With Tendulkar gone and with him a couple of other top-order batsmen ba c k in the pavilion, we also knew in our hearts it was all over.

Since that night, there’s been lot of debate about our decision to bowl first after winning the toss. There have been accusations of match-fixing, accusation that Azhar went against what was decided in the team meeting. At its most charitable, the criticism held us guilty of misreading the pitch and going against the wisdom of having runs on the board in a big match.

Truth be told, there was no devious motive. I can vouch for that. The consensus in the team meeting was that Sri Lanka had been chasing extremely well, and they had walloped us when batting second in the league games. We didn’t want to them to chase. The approach was a little negative, but they had riding this incredible wave of chasing and winning that we wanted to put them off their-comfort zone.

-theprint

15 Nov 2024 21 minute ago

15 Nov 2024 23 minute ago

15 Nov 2024 35 minute ago

15 Nov 2024 1 hours ago

15 Nov 2024 2 hours ago