05 Oct 2023 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Before a new chapter is written, relive past glories with a look back at all the previous editions of one-day cricket's showpiece event

1975

Host: England

Winner: West Indies (defeated Australia by 17 runs)

Player of Final: Clive Lloyd (WI)

Player of Tournament: N/A

Competing Teams: 8 (Australia, East Africa, England, India, New Zealand, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, West Indies)

Most Runs: Glenn Turner (NZ ) - 333 at 166.5; SR 68.5

Most Wickets: Gary Gilmour (Aus) - 11 at 5.6; SR 13.1

While the first global limited-overs tournament was the women’s World Cup staged in 1973, England was also named as host of the inaugural men’s showpiece two years later. The event took place over two weeks at the start of northern summer, with two reserve days set aside for each of the 15 matches scheduled for the eight competing teams.

Prize money in the dying days of the non-professional era amounted to £9000 (around $A126,000 in today's currency) for the eventual winners, with £2000 ($A28,000 today) to be shared by the runners-up.

The most striking element of the maiden competition was the near-uniform unfamiliarity with the embryonic format. County cricket regulars had been exposed to 60-over cricket through the UK Sunday league, but eventual finalists Australia and West Indies boasted just seven and two ODIs' experience respectively heading into the tournament.

Despite their recent Ashes hammering in Australia, England were duly installed second-favourites behind the West Indies who lost 38-year-old all-rounder Garfield Sobers to a groin injury pre-tournament. Australia's hopes suffered a setback when they lost a warm-up game to a little-known East Canada XI during a Toronto stopover en route to London.

However, Australia honoured skipper Ian Chappell's pledge to fight "all the way" through the Cup and reached the final at Lord's against Clive Lloyd's West Indies. The game was deemed to be of such significance a rare satellite feed beamed pictures across the world, although the absence of spin bowlers coupled with an 11am start time meant the full 120 overs would stretch until almost nightfall.

Australia's game plan was so straightforward – hoping their quicks bowled out the opposition for a gettable score - it did not require a pre-game meeting. However, when the West Indies innings ended at 4pm that total was a daunting 291 due to Lloyd's blazing 102 off 85 balls.

Viv Richards' hat-trick of run-outs was the defining feature of Australia's pursuit, and after a series of premature pitch invasions by exuberant West Indies fans and a defiant last-wicket effort from Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson, the game was fittingly resolved by the innings’ fifth run out shortly before 8.45pm with Lloyd's men crowned inaugural champions.

1979

Host: England

Winner: West Indies (defeated England by 92 runs)

Player of Final: Viv Richards (WI)

Player of Tournament: N/A

Competing Teams: 8 (Australia, Canada, England, India, New Zealand, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, West Indies)

Most Runs: Gordon Greenidge (WI) – 253 at 84.3; SR 62.32

Most Wickets: Mike Hendrick (Eng) – 10 at 14.9; SR 33.6

The second iteration of the men’s limited-overs showcase was played under the heavy shadow of Kerry Packer’s World Series Cricket, an enterprise that itself grew out of the reluctance of cricket’s power brokers to share the hefty £1.8m profit from the 1975 event with the players. The truce ending cricket’s war was signed weeks before the 1979 tournament kicked off, with England again hosting despite India’s interest in taking it on.

Cup holders West Indies were almost unbackable favourites to defend their crown due to their battery of fast bowlers that meant protective batting helmets became an essential bit of kit. However, Australia were not expected to seriously challenge given their refusal to select the rump of star players who had defected to WSC, with Dennis Lillee attending the tournament in the guise of a journalist.

Losses to England and Pakistan in the group stage meant Kim Hughes’s team knew they would not progress to the play-off rounds before their consolation win over Canada.

England’s familiarity with conditions and the 60-over format ensured they progressed to their first final, but lost premier fast bowler Bob Willis to a knee injury and relied heavily on part-timers Geoff Boycott, Graham Gooch and Wayne Larkins in the final. After a shaky start, West Indies pair Viv Richards and Collis King put on 139 for the fifth wicket to swing the game.

England’s ponderous pursuit of 287 saw openers Boycott and Mike Brearley take 38 overs to put on 129 which meant the batters behind them had to throw caution to the wind, with the final eight wickets tumbling for 11 runs to hand West Indies their second trophy.

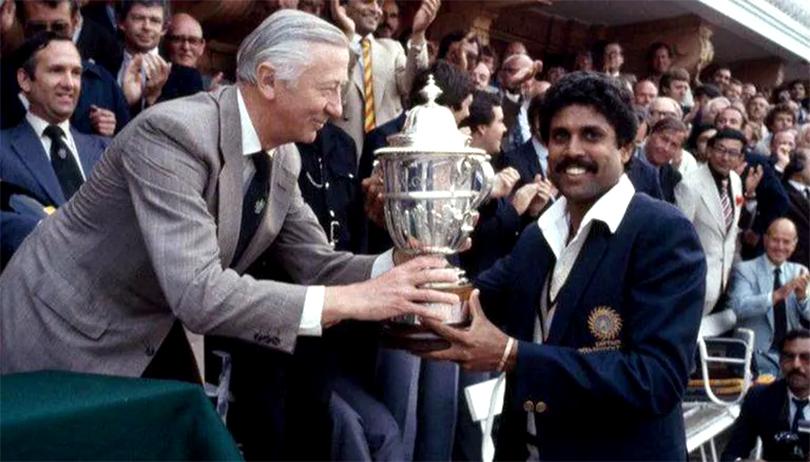

1983

Host: England/Wales

Winner: India (defeated West Indies by 43 runs)

Player of Final: Mohinder Amarnath (Ind)

Player of Tournament: N/A

Competing Teams: 8 (Australia, England, India, New Zealand, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, West Indies, Zimbabwe)

Most Runs: David Gower (Eng) – 384 at 76.8; SR 84.8

Most Wickets: Roger Binny (Ind) – 18 at 18.7; SR 29.33

Another cloud enshrouded the third World Cup, this time the spectre of lucrative rebel tours being staged in South Africa which remained a sporting pariah due to the nation’s race-based apartheid laws. Players from England, West Indies and Sri Lanka had been lured there and were subsequently issued bans that varied from a couple of years to life by their home administrations.

The profile that grew from the first two World Cups also meant one-day internationals had proliferated on the global schedule, with the 28 ODIs played between the first two Cup tournaments dwarfed by the 122 staged from 1979 to 1983, with post-Packer Australia hosting a bulk of those.

The tournament itself expanded, not in the number of competitors but the volume of matches with each team playing each other twice to reduce the possibilities of a ‘freak’ result shaping the final rounds. Despite the expansion from 14 to 27 games, the event was still contained within two weeks although the schedule required the use of non-Test venues such as Taunton and Tunbridge Wells.

Other changes in 1983 included the introduction of fielding restrictions with two 30m circles, but there was no change to tournament favouritism with West Indies expected to complete a three-peat given England had lost key players to the rebel ban.

In a bid to fight Caribbean firepower with fire, Australia loaded up on fast bowlers with Lillee, Thomson, Rodney Hogg and Geoff Lawson and they were installed as third-favourite alongside Pakistan. But a humiliating loss to non-Test nation Zimbabwe in the first round, and to 66-1 outsiders India in the last meant Australia failed to progress past the group phase for the second successive tournament.

With charismatic all-rounder Kapil Dev elevated to the captaincy in place of Sunil Gavaskar, India emerged as the first genuine bolter in the tournament’s short history and won through to the final against the peerless West Indies.

So confident were the reigning champions of completing a hat-trick, star fast bowler Malcolm Marshall placed an order for a luxury car he planned to pay for with winners’ prizemoney. It seemed a prudent investment when India stumbled to 183, with their attack comprising mostly medium-pacers not expected to trouble the West Indies strokemakers.

However, after Kapil’s famous running catch to remove Viv Richards and with Clive Lloyd hobbled by a leg injury, the India skipper noted to umpire Harold ‘Dickie’ Bird ‘we will win after all … they think it is too easy’. No West Indies batter reached 35 as they were humbled for 140, prompting pandemonium around Lord’s and an immediate public holiday called in India.

The upset win changed the face of international cricket overnight as the limited-overs game became the pre-eminent format in India. Within a year, the ICC announced the next World Cup would be staged on the sub continent.

1987

Host: India/Pakistan

Winner: Australia (defeated England by 7 runs)

Player of Final: David Boon (Aus)

Player of Tournament: N/A

Competing Teams: 8 (Australia, England, India, New Zealand, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, West Indies, Zimbabwe)

Most Runs: Graham Gooch (Eng) – 471 at 58.9: SR 70.5

Most Wickets: Craig McDermott (Aus) – 18 at 18.9; SR 24.3

The South Africa issue continued to haunt the 1987 tournament, with the Indian government insisting they would only grant visas to players who had partaken of rebel tours if they publicly denounced apartheid.

Of greater consequence, however, was the reduced daylight hours in Asia necessitating a reduction to 50-over games with an early (9am) start time and each innings to be capped at three and a half hours. A new sponsor meant a fresh trophy, neutral umpires were introduced and the greater travel distances between venues across India and Pakistan meant the tournament grew to four weeks.

India’s triumph of 1983 had not translated to ongoing success in subsequent years, and the crackdown on short-pitched bowlers had further blunted the West Indies’ waning influence. England had rebuilt their team after the rebel tours, and even though star all-rounder Ian Botham opted out of the 1987 event they were expected to perform well, as were co-hosts Pakistan even though their talismanic leader Imran Khan was aged 35 and indicated it would be his final World Cup.

Following two failed campaigns, Australia sent a young team under new skipper Allan Border but expectations were so low that Channel Nine opted not to exercise their broadcast rights and provide live telecasts of matches. However, the exhaustive training regime implemented by Border and coach Bob Simpson meant Australia were the best-drilled outfit and they built momentum throughout.

They reached the final at Eden Gardens in Kolkata as crowd favourites, having ended the hopes of India’s arch-rival Pakistan and squared off with colonial oppressor, England, in the decider. Preparation of the final pitch was overseen by Adelaide Oval curator Les Burdett, and Australia enjoyed first use reaching 1-150 after 34 overs and eventually posting 253. England’s chase hit early hurdles but was back on track until Mike Gatting’s infamous reverse sweep against the first ball sent down by rival skipper Border.

In the lengthening shadows and before a huge and exultant crowd, Australia missed a couple of outfield chances but held their nerve to secure their first World Cup, marking the nation’s renaissance as a cricket force in both forms of the men’s game. It also saw the white-ball game shed its last remaining links with its Test-match forebear.

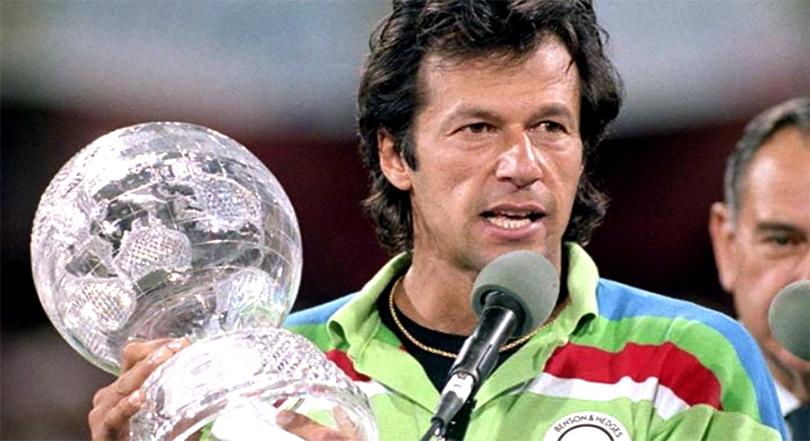

1992

Host: Australia/New Zealand

Winner: Pakistan (defeated England by 22 runs)

Player of Final: Wasim Akram (Pak)

Player of Tournament: Martin Crowe (NZ)

Competing Teams: 9 (Australia, England, India, New Zealand, Pakistan, South Africa, Sri Lanka, West Indies, Zimbabwe)

Most Runs: Martin Crowe (NZ) – 456 at 114.0; SR 90.7

Most Wickets: Wasim Akram (Pak) 18 at 18.8; SR 29.9

The first southern hemisphere World Cup ushered in the most radical changes the tournament had witnessed. The innovations pioneered by the Packer revolution – coloured clothing, floodlights, two white balls per innings, electronic scoreboards and replay screens – were adopted, along with the lucre of tobacco sponsorship. Modernity was also reflected in a new glass-orb trophy.

The number of competing teams also swelled following South Africa’s return to international competition, with recently released political prisoner Nelson Mandela giving his blessing to the nation’s re-admission to cricket circles. The number of matches duly grew to 39, but that put paid to reserve days so a formula utilising the lowest-scoring overs of an opponent’s innings was devised to decide rain-affected matches.

Australia’s reluctance to have the tournament interfere with its lucrative summer schedule of Tests and ODIs meant the World Cup was staged in February-March, with the larger of the co-hosts installed as favourite given their form during the preceding summer. England were tipped to again be a contender with Botham available after a season of children’s pantomime in the UK, and Pakistan’s bowling depth again loomed large despite the absence through injury of young star Waqar Younis.

India had been in Australia since November for Test and ODI commitments that announced the arrival of Sachin Tendulkar, and West Indies opted to leave out Viv Richards with his protégé Brian Lara assuming the mantle of batting stardom. New Zealand were rated 14-1 outsiders but outshone their co-hosts whose inability to advance past the group stage prompted a radical revamp of Australia’s approach to white-ball cricket and, eventually, the rise of separate Test and ODI teams.

England reached yet another final on the back of a farcical rain-affected semi-final that saw South Africa eliminated, which ensured Pakistan entered the decider at the MCG as crowd favourites. The only two players to have endured from the inaugural 1975 tournament – Imran Khan and Javed Miandad – were crucial in carrying Pakistan to 249.

That target grew more daunting when Botham was adjudged caught behind in young tyro Wasim Akram’s first over, and when the final wicket fell a number of Pakistan players dropped to their knees and kissed the turf in celebration. Accepting the trophy, Imran called time on his storied cricket career and crowned his nation’s finest sporting moment.

1996

Host: India/Pakistan/Sri Lanka

Winner: Sri Lanka (defeated Australia by seven wickets, 22 balls remaining)

Player of Final: Aravinda de Silva (SL)

Player of Tournament: Sanath Jayasuriya (SL)

Competing Teams: 12 (Australia, England, India, Kenya, Netherlands, New Zealand, Pakistan, South Africa, Sri Lanka, United Arab Emirates, West Indies, Zimbabwe)

Most Runs: Sachin Tendulkar (Ind) – 523 at 87.2; SR 85.9

Most Wickets: Anil Kumble (Ind) – 15 at 18.7; SR 27.9

The commercial success of the two tournaments staged beyond cricket’s homeland meant England lobbied hard to regain hosting rights in 1996, but ultimately it was the strength of that financial support in sub continental Asia that saw the World Cup return there.

The rise of cable television helped drive further innovations such as replay assistance for umpires in deciding run outs and stumpings, as well as the addition of corporate logos on the playing surface and stumps. More money meant more teams, with a further three added as reward for success at the newest global offering, the ICC Trophy. But total number of matches was reduced to 37 as the pool format of the earlier tournaments was reinstated.

Weeks before the opening game, a terrorist bomb detonated in Colombo killing 80 people and Australia and West Indies opted to forfeit their scheduled matches in the Sri Lanka capital as a result. Regardless, Australia remained favourites on the strength of a revamped team that featured young talent the likes of Shane Warne, Glenn MacGrath and Ricky Ponting but the couple of walkover results in addition to their enterprising top-order batting meant Sri Lanka emerged as the most successful of the three host countries. The island nation reached their first World Cup final after their semi-final encounter against India at Eden Gardens ended in a riot among fans as the home team slid towards defeat.

Despite entering the decider as overwhelming favourite, signs for Australia were ominous when the pre-game ceremony belted out the South African anthem instead of Advance Australia Fair. Then, before Sri Lanka began their pursuit of 242 the lights went out at Gadaffi Stadium in Lahore. When they blazed back into life, Australia were surprised to see the amount of evening dew that had settled on the playing surface.

Not only did the moisture ensure the ball skidded through helpfully off the pitch, it proved near impossible to grip for leg spinner Warne who was Australia’s premier bowling threat. Led by Aravinda de Silva’s imperious 107, the underdogs stormed home to become the third Asian nation to lift the trophy, a new 3kg sterling silver version created by London crown jeweller Garrard and Co.

1999

Host: UK/Ireland/Netherlands

Winner: Australia (defeated Pakistan by eight wickets, 179 balls remaining)

Player of Final: Shane Warne (Aus)

Player of Tournament: Lance Klusener (SA)

Competing Teams: 12 (Australia, Bangladesh, England, India, Kenya, New Zealand, Pakistan, Scotland, South Africa, Sri Lanka, West Indies, Zimbabwe)

Most Runs: Rahul Dravid (Ind) – 461 at 65.9; SR 85.5

Most Wickets: Geoff Allott (NZ) – 20 at 16.2; SR 26.3

After 16 years, the Cup returned to England in a vastly different guise to when it left. As further incentive for the wildcard teams, a Super Six round was introduced after the group games to decide which outfits would win through to the final four. It meant the tournament filled more than five weeks, although the need to accommodate England’s international commitments meant it began amid the mid-May chill and concluded before the summer solstice.

In light of the late spring timing, a new mathematical formula calculated by statisticians Frank Duckworth and Tony Lewis was introduced to decide rain-affected matches. More eye-catching were the bold new uniforms that integrated elements of competing teams’ national flags on luminescent fabric.

Boasting a team stocked with all-rounders, South Africa were installed favourites for yet another imagining of the World Cup trophy which has since been retained as the perpetual keepsake. The convoluted format of a tournament within a tournament threw up only one genuine surprise, with Zimbabwe progressing while the host nation endured a horror campaign and did not.

Having lost two of their first three group games, Australia seemed destined to join their Ashes rivals as early casualties but Steve Waugh’s team found their feet and then their form to storm into the semi-finals. Their tied game against South Africa at Edgbaston stood as the benchmark for World Cup matches across the next two decades, and was the zenith of the tournament that fizzled in the final.

Pakistan’s mercurial batting touch deserted them on the big stage as Warne spun his web, and even allowing for a delayed start due to morning rain at Lord’s the one-sided result was reached by 4.30pm as Australia reached their target with barely a hiccup. It would be a further 12 years before they experienced World Cup defeat.

2003

Host: South Africa/Kenya/Zimbabwe

Winner: Australia (defeated India by 125 runs)

Player of Final: Ricky Ponting (Aus)

Player of Tournament: Sachin Tendulkar (Ind)

Competing Teams: 14 (Australia, Bangladesh, Canada, England, India, Kenya, Namibia, Netherlands, New Zealand, Pakistan, South Africa, Sri Lanka, West Indies, Zimbabwe)

Most Runs: Sachin Tendulkar (Ind) – 673 at 61.2; SR 89.3

Most Wickets: Chaminda Vaas (SL) – 23 at 14.4; SR 23.0

The World Cup continued its growth in both scope and reach, with 14 teams contesting the first tournament to be staged in Africa. While 54 games over six weeks posed a logistical challenge, it was the scheduling of matches in Harare and Nairobi that created most angst with England and New Zealand opting to forfeit their matches in those hot spots, a decision that effectively cost both teams a place in the Super Sixes round.

South Africa’s hopes of amending their 1999 lapse in front of euphoric home fans ended when another mathematical miscalculation saw them eliminated at the group phase, but their failure paved the way for Kenya to become the first non-Test nation to reach the semi-finals.

Australia’s pre-tournament favouritism was dented when Warne recorded a positive test to a banned substance and was sent home prior to his team’s opening game. But from there, Ricky Ponting’s men scarcely missed a beat and were undefeated heading into their third consecutive World Cup final.

India’s path to their first decider since the 1983 triumph was built on their top-order batting strength, but their bowling was brutally exposed by an opening stand of 105 in 14 overs between Adam Gilchrist and Matthew Hayden before Ponting played the innings of his life. His masterly 140 was complemented by 88 from Damien Martyn who batted with a broken thumb, and any hope of India getting close were effectively ended in the first over of their reply when Tendulkar perished for four.

The threat of a High-Veld thunderstorm held off long enough for Australia to complete a flawless campaign, and join West Indies as the only back-to-back World Cup champions. No team had managed three on the trot.

2007

Host: West Indies

Winner: Australia (defeated Sri Lanka by 53 runs D/L method)

Player of Final: Adam Gilchrist (Aus)

Player of Tournament: Glenn McGrath (Aus)

Competing Teams: 16 (Australia, Bangladesh, Bermuda, Canada, England, India, Ireland, Kenya, Netherlands, New Zealand, Pakistan, Scotland, South Africa, Sri Lanka, West Indies, Zimbabwe)

Most Runs: Matthew Hayden (Aus) – 659 at 73.2; SR 101.1

Most Wickets: Glenn McGrath – 26 at 13.7; SR 18.6

More than 30 years after lifting the inaugural men’s World Cup, West Indies were granted hosting rights. The USA had lobbied to also host matches but the ICC voted to keep it solely in the Caribbean. The resultant cost of redeveloping venues to meet the burgeoning demands of a globally televised, heavily sponsored event – reputedly in excess of $US300m – placed a huge financial impost on West Indies cricket, which has continued to pay a heavy price in the years since.

Those demands were heightened by the increase to 16 competing teams, although another tweak to the format that brought four pool groups followed by a Super Eight format reduced the total number of matches to 51. Technology also increased its footprint, with umpires granted the power to refer disputed catches to an off-field official.

The tournament made headlines for the grimmest reason when Pakistan coach Bob Woolmer was found dead in his Jamaica hotel room the day after his team was knocked out of the event. Despite initial claims to the contrary, it was eventually declared death by natural causes.

On-field, Ireland followed Kenya’s success four years earlier to reach the Super Eights round, as did Bangladesh although neither team was expected to seriously challenge Australia who justified their favouritism by reaching a fourth successive final without dropping a game.

The decider against Sri Lanka was reduced to 38 overs a side following morning rain in Barbados, before another blazing start by Gilchrist and Hayden saw the former post the highest individual score in a World Cup final – 149 from 104 balls. Sri Lanka retained hope of chasing the distant 202 while champion batters Kumar Sangakkara and Mahela Jayawardene were at the crease, but their dismissals followed by a further rain interruption put paid to the contest.

In failing light, umpires offered the light with Sri Lanka needing 61 from the final three overs, then interrupted Australia’s victory celebration with the ludicrous proposition the game be completed the following day. However, Jayawardene argued that was pointless and instructed his batters to keep going while his rival skipper Ponting agreed to bowl spinners in near-total darkness until the inevitable result was reached.

2011

Host: India/Bangladesh/Sri Lanka

Winner: India (defeated Sri Lanka by six wickets, 10 balls remaining)

Player of Final: Mahendra Singh Dhoni (Ind)

Player of Tournament: Yuvraj Singh (Ind)

Competing Teams: 14 (Australia, Bangladesh, Canada, England, India, Ireland, Kenya, Netherlands, New Zealand, Pakistan, South Africa, Sri Lanka, West Indies, Zimbabwe)

Most Runs: Tillakaratne Dilshan (SL) – 500 at 62.5; SR 90.7

Most Wickets: Shahid Afridi (Pak) – 21 at 12.9; SR 21.3; Zaheer Khan (Ind) – 21 at 18.8; SR 23.3

Host nations for the 2011 World Cup were initially to include Pakistan, but after the 2009 terror attack in Lahore where the Sri Lanka team and match officials came under gun fire during a Test match, the ICC was forced to revise that plan.

Pakistan officials then suggested the tournament be handed to Australia and New Zealand, with the original Asian hosts granted the right to stage it in 2015 but that was roundly rejected by India, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh. The requirements demanded of host venues meant two new stadia had to be built in Sri Lanka, while Eden Gardens – site of the 1987 final – was deemed unfit to host and the match allocated to Kolkata was duly shifted to Bengaluru.

The introduction of high-definition television pictures also made possible the implementation of a Decision Review System (DRS) to aid on-field umpires.

For the first time since the tournament’s inception, the number of competing teams underwent a reduction, to 14, and the format from the 1996 event reinstated with two groups of seven engaging in a round-robin before the top four squared off in sudden-death play-offs. A total of 49 matches.

With a nucleus of their Cup-winning squads having departed the game, Australia fielded a new-look outfit which – for the first time in five global tournaments – failed to reach the ultimate match, bowing out to host nation India in a semi-final.

And in another first, co-hosting nations India and Sri Lanka met in the final in front of a fanatical crowd at Mumbai’s Wankhede Stadium. Indeed, the noise was so great at the coin toss, ICC match referee Jeff Crowe couldn’t hear Sri Lanka skipper Kumar Sangakkara’s call and the coin had to be flipped again.

A television audience purported to be around half a billion saw Sri Lanka post 274 thanks largely to Mahela Jayawardene’s 103 off 88 balls but a polished 97 from Gautim Gambhir and a rollicking 91no off 79 balls by Mahendra Singh Dhoni carried India to a second World Cup crown, and the first team to complete a win on their home turf.

2015

Host: Australia/New Zealand

Winner: Australia (defeated New Zealand by seven wickets, 101 balls remaining)

Player of Final: James Faulkner (Aus)

Player of Tournament: Mitchell Starc (Aus)

Competing Teams: 14 (Afghanistan, Australia, Bangladesh, England, India, Ireland, New Zealand, Pakistan, Scotland, South Africa, Sri Lanka, United Arab Emirates, West Indies, Zimbabwe)

Most Runs: Martin Guptill (NZ) – 547 at 68.4; SR 104.6

Most Wickets: Mitchell Starc (Aus) – 22 at 10.2; SR 17.4; Trent Boult (NZ) – 22 at 16.9; SR 23.2

The World Cup Australia and New Zealand had hoped to host in 2011 – when theirs was the only bid to be lodged with the ICC by the appointed deadline for that tournament – eventually took place four years later amid a summer of heavy sadness. The death of Australia batter Philip Hughes months earlier had cast a pall over the game, and weighed heavily on captain Michael Clarke who became hellbent on proving himself fit and leading his team to glory.

The event maintained the same number of teams and match format as the previous iteration, even though the ICC had decided after the 2011 tournament it should be reduced to the then-10 Test-playing nations. That decision was reversed amid protests by and on behalf of associate members.

Consequently, the most notable innovation of the 2015 World Cup was the provision of a super over to decide any match that might finish in a tie.

As the world’s top-ranked team playing on home turf, Australia were installed as even money favourites ahead of South Africa, co-hosts New Zealand and vanquished finalist from the preceding two tournaments, Sri Lanka. India and Pakistan were considered comparative outsiders, thought tickets for their meeting at the 50,000-capacity Adelaide Oval sold out in 12 minutes.

England’s failure to progress past the group stage hardly rated as a surprise given their luckless World Cup history to that point, though the fact their fate was sealed by a loss to Bangladesh was newsworthy.

Ultimately, six weeks after they had hosted joint opening ceremonies in Christchurch and Melbourne respectively, Australia and New Zealand met in the final, the second time in as many tournaments the trophy had been fought out by co-hosts.

Hopes of a Kiwi fairytale were effectively ended when New Zealand’s inspirational skipper Brendon McCullum had his stumps skittled by Mitchell Starc in the opening over, and his team laboured from that point reaching 3-99 midway through the innings before posting 183.

As if carried by divine providence in front of a record ODI crowd of 93,013 at the MCG, Clarke top-scored with 74 in Australia’s pursuit which they completed with almost 15 overs up their sleeves, and dedicated the triumph to the memory of his fallen mate.

2019

Host: England/Wales

Winner: England (defeated New Zealand on boundary countback with scores tied after super over)

Player of Final: Ben Stokes (Eng)

Player of Tournament: Kane Williamson (NZ)

Competing Teams: 10 (Afghanistan, Australia, Bangladesh, England, India, New Zealand, Pakistan, South Africa, Sri Lanka, West Indies)

Most Runs: Rohit Sharma (Ind) – 648 at 81.0; SR 98.3

Most Wickets: Mitchell Starc (Aus) – 27 at 18.6, SR 20.5

With the Cup returning to the country of its birth 44 years earlier, but with England’s name still glaringly absent from the honour board, Australian-born coach Trevor Bayliss was recruited with the singular aim of taking the three-time runner-up one step further.

The move to reduce the competition to 10 teams was finally ratified, and the schedule reverted to the round-robin format of 1992 – symbolically, the year of England’s most recent final appearance – with a total of 45 matches stretched over six weeks and no provision for reserve days despite the UK’s reputation for fickle weather. In total, four games were lost to rain.

With the number of Test-playing nations increased to 12, the reduction in World Cup participants meant Zimbabwe and Ireland missed out after two-times champions West Indies and newly elevated Afghanistan won through the qualifying fixtures. It was therefore the first World Cup to be staged without at least one associate nation represented. The other startling difference from the inaugural event in 1975 was the spike in prizemoney on offer - $US4m for the winners, half that bounty for the runners-up.

With the top four teams advancing to the semi-finals, Pakistan were unluckiest losers having missed the play-off games on net run rate. And the elimination of Australia and India at the penultimate hurdle meant the only two teams to have been part of every previous World Cup without ever lifting the trophy – England and New Zealand – would fight it out to break their respective ducks.

True to their tortured histories, New Zealand posted a middling total of 241 only for England to slump to 4-86 in the 24th over before Ben Stokes and Jos Buttler combined. A fortuitous boundary claimed when an overthrow rebounded to the fence off Stokes’ bat in the desperate final over ensured scores finished tied, although umpire Kumar Dharmasena later conceded he had erred in not deducting one run from England’s total given the batters hadn’t crossed when the ball was thrown.

It proved a critical judgement, as scores remained deadlocked after the supposedly decisive super over that followed and England were awarded the trophy because of a superior boundary count (26 to 17) across the entire match.

The ICC has since scrapped the boundary count rule, and as many super overs as required to provide a definitive winner will follow. (cricket.com.au)

24 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

24 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

24 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

24 Nov 2024 8 hours ago

24 Nov 2024 8 hours ago