29 Jul 2017 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By D.B.S. Jeyaraj

Thirty years ago on this day (July 29th 1987) an accord was signed by the then Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and Junius Richard Jayewardene the then President of Sri Lanka in Colombo that had far reaching implications for both the tear drop island in the Indian Ocean and its giant neighbour.

The India - Sri Lanka Accord known popularly as the Indo-Lanka peace accord was hailed then as a great breakthrough in relations between India and Sri Lanka. Two related letters known as “annexures” were also signed by both leaders.

The preamble of the accord reads as follows –

“The President of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, his Excellency Mr. J.R. Jayewardene, and the Prime Minister of The Republic of India, His Excellency Mr. Rajiv Gandhi, having met at Colombo on July 29, 1987”.

“Attaching utmost importance to nurturing, intensifying and strengthening the traditional friendship of Sri Lanka and India, and acknowledging the imperative need of resolving the ethnic problem of Sri Lanka, and the consequent violence, and for the safety, wellbeing and prosperity of people belonging to all communities of Sri Lanka. Have this day entered into the following agreement to fulfil this objective”.

In realistic terms the accord of July 29th 1987 was a triumph for Indian coercive diplomacy. It was opposed by (and still is) significant sections of the Sri Lankan people.

A flashpoint indicative of the simmering tension that prevailed then was the attempted assault of the visiting Indian premier by a Sri Lankan naval rating Vijaya Rohana de Silva Wijemuni. The Naval Rating, who was part of the Navy Guard of Honour being inspected by Rajiv Gandhi, took a swipe with his rifle at the Indian Premier’s head.

Mercifully Rajiv saw the swinging rifle from the corner of his eye. He sidestepped deftly and ducked swiftly.

Instead of reaching out to the affected victims of the July 1983 pogrom and alleviating their hardship the JR regime was hell bent on appeasing the majority. Blaming the Victim syndrome was seen at its best then.

The firearm struck his shoulder. Had that blow been fatal, Indo-Lanka relations may have changed drastically in favour of the Sri Lankan Tamil people. However, the very same Rajiv Gandhi who survived the “Sinhala” assault in 1987 could not escape death when a Sri Lankan Tamil girl known by the nom de guerre “Dhanu” with explosives strapped to her body blew herself up at a place in Tamil Nadu called Sriperumbudoor in 1991.

The political pendulum in India swung sharply against the Sri Lankan Tamils thereafter.

Indian High Commissioner Jyotindra Nath Dixit

Foremost among the many architects of the accord was former Indian High Commissioner in Colombo Jyotindra Nath Dixit known as “Mani” Dixit. Twenty months after the signing of the accord J.N. Dixit delivered a lecture on Sri Lanka at the United Services Institution in New Delhi on March 10, 1989. Dixit summed up the rationale for exercising Indian “power” immorally to coerce Sri Lanka into signing the accord thus - “The chemistry of power, the motivations which affect the interplay of power between societies are not governed by absolute morality. ......…It is an external projection of our influence to tell our neighbours that if, because of your compulsions or your aberrations (sic.), you pose a threat to us, we are capable of, or we have a political will to project ourselves within your territorial jurisdiction for the limited purpose of bringing you back.

“Sounds slightly arrogant! It is not arrogant. It is real-politik, and it brings you back to the path of detachment and non-alignment where you don’t endanger our security.”

The irony in all this was that the signatory on the Sri Lankan side was President J. R. Jayewardene. JR as he was popularly known was steeped in historical knowledge being an avid reader of history books. He had the uncanny ability at times to predict the future course of events in International relations. JR was concerned about the position of Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) vis-a-vis India ( pre-partition) after the British granted independence. The writing was on the wall for the British Empire even as the second World War was raging.

Jayewardene foresaw a potential threat from India after both countries attained freedom from the British.

JR Jayewardene along with Dudley Senanayake had been elected Joint Secretaries of the Ceylon National Congress in 1940. In this capacity JR interacted with several leaders of the Indian National Congress. One of them was Jawaharlal Nehru who went on to become Independent India’s first Prime Minister in 1947. Nehru who served as Premier till 1964 was the father of Indira Gandhi, Grandfather of Rajiv Gandhi and Great -grandfather of Rahul Gandhi.

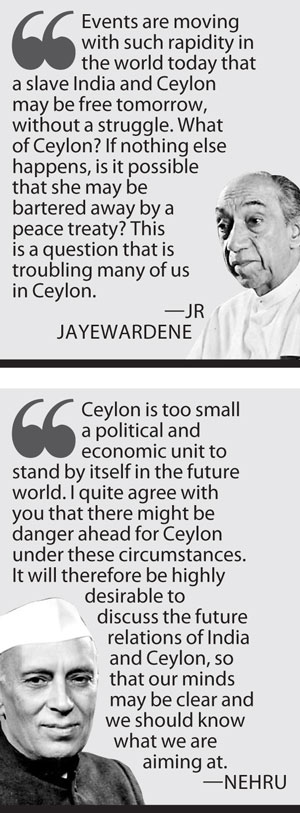

On July 20, 1940, JR Jayewardene wrote to Jawaharlal Nehru: “Events are moving with such rapidity in the world today that a slave India and Ceylon may be free tomorrow, without a struggle. What of Ceylon? If nothing else happens, is it possible that she may be bartered away by a peace treaty? This is a question that is troubling many of us in Ceylon.”

Nehru replied on August 1, 1940:

“Ceylon is too small a political and economic unit to stand by itself in the future world. I quite agree with you that there might be danger ahead for Ceylon under these circumstances. It will therefore be highly desirable to discuss the future relations of India and Ceylon, so that our minds may be clear and we should know what we are aiming at.”

‘Monroe Doctrine’ of USA in the Indian Ocean

Even if JR’s worries may have been laid to rest by Nehru’s reply at that time, post - independence course of events evoked fresh doubts and misgivings. In 1954 JR was Minister for Agriculture and Food in the Govt. of Prime minister Sir John Kotelawela. The South Asian Prime Ministers’ Conference was held in Colombo that year. On March 19, 1954 Jayewardene sent a memorandum to his Prime Minister. In that he alluded to the Monroe doctrine of the USA and emphasised that India should not be allowed to play a similar role in the Indian Ocean region.

JR wrote:

“If we look again at the American scene, we see that the U.S.A. so long ago as 1823 enunciated the Monroe Doctrine and exercised supervision over the entirety of the American Continents, both North and South. It is therefore necessary to see that the states in this region are not cut off from the rest of the world from economic or military aid, such as Pakistan has recently secured from America. India should not be permitted to proclaim a “Monroe Doctrine” in the Indian Ocean where she will play the role that the U.S.A. plays in the Atlantic.”

Yet, through a quirk of fate the very same JR Jayewardene, who foresaw the potential danger of Indian domination decades ago and was keen on preventing it, happened to be the Sri Lankan leader who bowed down to New Delhi and accepted Indian overlord-ship by way of the accord and annexures in 1987.

Tamil National Alliance (TNA) Spokesperson and Jaffna District parliamentarian M. A. Sumanthiran in a recent article in “The Hindu” observes thus –

“The Indo-Sri Lanka Accord itself was unique in that it was a bilateral international agreement between two sovereign nations, where one promised the other that an internal political rearrangement would be made in order to solve the Tamil national question. It was indeed ironic that a President (Jayewardene) who popularised and deified the concept of “unity, sovereignty and territorial integrity of Sri Lanka” assured the neighbour as to how he would solve an “internal” political question and then invited the Indian Army into Sri Lanka to help implement the accord”.

What then led to this perceived “downfall” on the part of Junius Richard Jayewardene? Why did the man who as a Cabinet Minister wanted to resist Indian supremacy in 1954 do an about turn in 1987 as Executive President and cave into Indian demands?

The course of events that led to this transition or transformation is a remarkable political tale by itself.

“Intermestic” Term Coined by Henry Kissinger

The “Tamil issue” is for Sri Lanka and India is an “intermestic” issue. The term “Intermestic” was first coined and used by Henry Kissinger to explain international issues having domestic economic implications like for instance the middle-eastern situation abroad impacting on the price of gas in the US. The term coined by Kissinger took the “inter” from International and “mestic” from Domestic.

It was however veteran Journalist and foreign affairs expert Mervyn de Silva who popularised the term in Sri Lanka.

The fundamental difference in New Delhi policy towards Pakistan in 1971 and Sri Lanka in 1987 was that in the case of the former it suited Indian interests to fracture Pakistan and create Bangladesh while in the case of the latter, Indian interests were better served by preventing dismemberment of Sri Lanka and unifying the Island by preventing the creation of “Tamil Eelam”.

Mervyn was then editing the “Lanka Guardian” fortnightly and writing a weekly column for “Sunday Island”.

Mervyn applied the term to all issues crossing the boundaries between the International and the domestic and belonged to both spheres thereby necessitating this sub-category.

According to Mervyn, Sri Lanka’s Tamil issue was for Sri Lanka a domestic issue with an international spillover and for India it was an international issue with a domestic spillover. Hence for both Colombo and New Delhi it should be regarded as INTERMESTIC, i.e. “at the interface of the international and the domestic”.

Generally countries act in their own self – interest but often attribute lofty motives for such actions .Indian involvement in the affairs of its neighbours has been described as benign intervention by Indian academics and analysts.

The undermining of the Rana family and empowerment of the Shah dynasty in Nepal, the dismemberment of Pakistan and creation of Bangladesh, the Indo-Lanka accord and induction of the Indian Army as a peace-keeping force in Sri Lanka and the quick action in Maldives to crush a coup d’etat aided by Sri Lankan Tamil militants of the PLOTE (Peoples Liberation Organization of Tamil Eelam ) are some instances of Indian benign intervention.

“Benign Interventions” Served India’s Interests

Needless to say all these cases of “benign intervention” also served India’s interests in the region. But such is the nature of international relations. All countries have their own interests at heart and smaller entities identifying common interests with larger interests and harmonising accordingly have greater chances of bettering the prospects for themselves.

In the case of Sri Lanka the twin tenets of basic Indian policy was preserving the unity and territorial integrity of Sri Lanka on the one hand and ensuring the rights of the minorities particularly the Sri Lankan Tamils on the other. This framework in essence was conditioned by the intermestic factor.

The 1983 July anti-Tamil pogrom saw more than 100,000 Tamils fleeing to Tamil Nadu as refugees. The presence of Tamil refugees on Indian soil was the “locus standi” for India to seek a greater role in Sri Lanka. Instead of reaching out to the affected victims of the July 1983 pogrom and alleviating their hardship the JR Jayewardene regime was hell bent on appeasing the majority. Blaming the Victim syndrome was seen at its best then.

The Govt. introduced the Sixth Amendment to the Constitution disavowing separatism. All MPs were required to take an oath to that effect to retain Parliamentary membership. The Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF) with sixteen MPs in Parliament refused to take the oath on a matter of principle.

As a result they forfeited their seats. The Sri Lankan Tamil voice was effectively driven away from Parliament.

Ex- TULF MP’s Took Up Residence in Tamil Nadu

Several ex-TULF MP’s including Opposition leader Appapillai Amirthalingam took up residence in Tamil Nadu. With more than a hundred thousand refugees on its soil providing a ‘locus standi’, New Delhi offered its good offices to mediate and bring about a negotiated political settlement.

There was an imperative need for India to intervene at that stage. The Sri Lankan Tamil issue was a crucial emotional issue for Tamil Nadu at that time. There was a fear that the mood may turn volatile and result in a law and order crisis. Also there had been a flourishing secessionist movement in Tamil Nadu at one time. It had been checked and transformed democratically. The former Tamil separatists were well integrated into the Indian fabric.

Now there was apprehension that the fabric may be torn and separatist tendencies revived because of the Sri Lankan Tamil crisis impacting on Tamil Nadu.

If secession was encouraged in Sri Lanka that could have a demonstration effect on other states including Tamil Nadu in India. If the Tamils were allowed to be continually victimised in Sri Lanka that too could radicalise Tamil Nadu in the long term . These parameters necessitated in India fashioning policy ensuring both the unity of Sri Lanka as well as Tamil rights.

Creating Bangla Desh and Preventing “Tamil Eelam”.

The fundamental difference in New Delhi policy towards Pakistan in 1971 and Sri Lanka in 1987 was that in the case of the former it suited Indian interests to fracture Pakistan and create Bangladesh while in the case of the latter, Indian interests were better served by preventing dismemberment of Sri Lanka and unifying the Island by preventing the creation of “Tamil Eelam”.

The intermestic nature of the issue had two additional aspects too. One was that New Delhi at that time feared an arc of encirclement by “hostile” forces. India feared a Washington-Tel Aviv- Islamabad axis. The Jayewardene Govt was seen as a Western puppet and lackey (after all JR had been nicknamed “Yankee Dickie” at one time).

It was necessary therefore to win over Colombo and bring Sri Lanka within the Indian orbit. The Tamil issue provided an opportunity to de-stabilise Sri Lanka and pressure Jayewardene into submitting to Delhi diktat.

In short there were three basic reasons for Indian intervention in Sri Lanka then.

Firstly the Jayewardene Govt was spurning “non – alignment” and taking Sri Lanka into a pro – Western orbit. Under prevailing conditions of the day New Delhi feared a Washington – Tel Aviv – Islamabad axis. India needed to bring Sri Lanka to “heel” and keep out undesirable elements out of the region.

Secondly there was the domestic imperative. There was much concern in Tamil Nadu for the plight of Tamils in Sri Lanka. Tamil Nadu was once home to a flourishing separatist movement. India was concerned about the fall – out from Sri Lanka on Tamil Nadu if the conflict escalated here.

The third was the unacknowledged personality factor. It is a fact that basic policy is formulated by the bureaucracy in India and that the political executive is guided by it. Individual leaders by force of their personality may effect a change in the style of implementation but cannot effectively change the substance of policy.

What happened here was that Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was not very fond then of President Jayewardene or Prime Minister Premadasa.

Allusion of Cow and Calf to Indira-Sanjay and Sirima-Anura

Indira Gandhi declared emergency in 1975 and imposed iron rule in India. She jailed her political opponents. Indira and her son Sanjay Gandhi were accused of being virtual dictators. When elections were held in March 1977 the Congress party that had ruled India from 1947 lost for the first time in 30 years. Both Indira and Sanjay lost in their constituencies of Raebareli and Amethi respectively. In July 1977 elections were held in Sri Lanka. The incumbent Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) Prime Minister and her son Anura Bandaranaike contested in the electorates of Attanagalle and Nuwara-eliya-Maskeliya respectively. The irrepressible Ranasinghe Premadasa made a comparison between India and Sri Lanka at election meetings. He repeated on numerous occasions that just as the cow and calf were booted out by the Indian people, the Sri Lankan voters too would reject the cow and calf here.

The allusion of cow and calf were to Indira-Sanjay and Sirima-Anura.

Just as the Congress lost in India, the SLFP lost in Sri Lanka but unlike in India the cow and calf won in Lanka.

Once a viable solution was arrived at, the Tamil armed struggle was expected to end. But the Tamils were not to be abandoned entirely.

Indira, however had got to know of Premadasa’s allusions and was not amused. In fact she was angry. Proctor S. Sivasubramaniam, the father of former Kopay MP S. Kathiravetpillai, was a family friend of the Nehru-Gandhi family. In conversation with Mr. Sivasubramaniam, Indira Gandhi expressed her resentment at the UNP and its perceived proximity to Morarji Desai’s Govt.

On the other hand the TULF by remaining fiercely loyal to Indira during her days of defeat had become closer to her. According to reputed Indian analysts, such as A. G. Noorani “Indira personalised her foreign policy. Her favourites were Sirimavo Bandaranaike, Sheikh Hasina and Benazir Bhutto. Her bete noires were Zia, the King of Nepal and JR Jayewardene.

Triple Factor Confluence in Indo-Lanka Relations

This triple factor confluence in Indo - Lanka relations during the Indira-JR period deemed it necessary that India made a “benign” intervention in Sri Lanka after Indira Gandhi was premier again in 1980. There was little love lost between the JR and Indira led Govts. The Brahmins of South Block were for an intervention in Sri Lanka for two objectives.

1) To help resolve the ethnic conflict within a united Sri Lanka but in a manner acceptable to Tamils,

2) Make Colombo accept New Delhi’s hegemony over the region and appreciate Indian security concerns and teach the Jayewardene regime a lesson while rewarding the TULF.

It was at this point that the July 1983 pogrom occurred. Thousands of Tamils fled as refugees to India. Indian interests in Sri Lanka were harmed. This provided a “locus standi” for India to intervene in Sri Lanka. Jayewardene then played into India’s hands by bringing in the 6th Amendment disavowing separatism.

This effectively disenfranchised the Tamil representatives in Parliament. JR also refused to talk directly to the TULF. This created an opportunity for India to step in and offer its “good offices” to bring about ethnic reconciliation.

India Followed Two-track Sri Lanka Policy

So, Gopalaswamy Parthasarathy became India’s official emissary tasked with evolving political rapprochement. But India followed a two – track policy. Tamil militant groups were trained and armed and housed on Indian soil. They were allowed to run political cum propaganda offices in Tamil Nadu publicly.

India’s objectives were clear. New Delhi wanted to use the Tamil militants as a cutting edge to destabilise the Jayewardene regime and also exert pressure on Colombo to deliver a political settlement.

Once a viable solution was arrived at, the Tamil armed struggle was expected to end. But the Tamils were not to be abandoned entirely. India would underwrite a political solution and maintain a physical armed presence in North – East Sri Lanka to protect the Tamils and help implement the political solution.

In such a situation the Indian State trained and armed Tamil militants into guerrilla organizations. The idea was to fight and destabilise the North-Eastern Provinces to a great extent.

Thereafter the Colombo Govt. would be compelled to turn to Delhi for assistance. That moment would be seized. Tamil Eelam was never on the cards. All this while New Delhi was offering its “good offices” to bring about a negotiated settlement. In the exercise of this two-track policy, Indian envoys would engage with Lankan leaders and Tamil politicians on the one hand while India backed Tamil militant groups such as the LTTE engaged in violence against the Sri Lankan state on the other.

Meanwhile, Indira Gandhi was assassinated in 1984 and her son Rajiv Gandhi succeeded her. Rajiv’s ascendancy saw the veteran Gopalaswamy Parthasarathy being ousted as India’s special envoy to Sri Lanka on the Tamil issue.

Foreign Secretary Romesh Bhandari functioned as emissary. He was followed by others such as P. Chidambaram, K. Natwar Singh and Rajah Dinesh Singh.

Foreign Secretaries too changed from Bhandari to Venkateswaran and then K.P. S. Menon. Despite these changes the basic continuity in Indian policy towards Sri Lanka remained.

Dixit Warned Jayewardene of “Unpredictable Consequences”.

There were many twists and turns but India’s strategy worked to a great extent for some time. But after the military operation in Vadamaratchy in May 1987 it appeared that Colombo was on the verge of wiping out the LTTE. At that point India demonstrated very clearly to Colombo that it would not be allowed to crush Tamil militancy. Indian High Commissioner J. N. Dixit met President Jayewardene and warned him of “unpredictable consequences”. Dixit writes about the meeting in his “Assignment Colombo” book in the following manner-

“In one of my meetings with President Jayewardene late in May 1987, I protested against the blockade of Jaffna and the impact of Sri Lankan military operations on Tamil civilians of the area. I informed Jayewardene of my discussions with Lalith Athulathmudali wherein I had conveyed the message that India would not countenance the fall of Jaffna to Sri Lankan forces when India was still engaged in mediation efforts. I reminded Jayewardene that Rajiv Gandhi’s messages to him were a clear indication that India would be compelled to take action to protect Tamil civilians. Jayewardene was quite upset and he described my remarks as interference in the domestic affairs. …............

“Jayewardene was not going to allow matters to rest in such obfuscations!

He said:

“Dixit, be precise. Tell me what you personally think will happen when you talk about “unpredictable consequences”.” I said: “You will forgive me for saying this Mr. President, the unpredictable consequences may be LTTE asking operational support from Tamil Nadu and it might end up with the break-up of Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka may not remain a united country.”

“Jayewardene looked at me in his typical droopy-eyed irritation and said: “Mr Dixit, we are a small country, but I want you to know that I will not succumb to terrorist violence regardless of what you are saying. And please also note that this violence has been and is being supported by your Government and your country.”

Mr Dixit, we are a small country, but I want you to know that I will not succumb to terrorist violence regardless of what you are saying.

“Shock and Awe” Operation to Intimidate Sri Lanka

Despite the bullying by Dixit, President Jayewardene continued to remain defiant but New Delhi performed a “shock and Awe” operation to intimidate Sri Lanka and its President further.

On June 4, 1987 India informed Sri Lanka of its decision to drop relief supplies over Jaffna. Bernard Tilekaratna, Sri Lanka’s High Commissioner to India at that time, recalled his personal experience in an article in The Island of December 10, 1997. Tilekaratna wrote as follows - “The President had offered to send Foreign Minister Hameed to discuss the developing crisis but India had already decided to send its Air Force planes not only five Antonov-22 transport planes but also four Mirage-2000 fighter planes, to escort them.”

“I had enough contacts in New Delhi to know that this move was planned some days in advance even though it was done in complete secrecy and no details were known. My information was that this would take place by air or through Indian warships and I had conveyed this to the President himself. When I was summoned to the Ministry of External Affairs by the then Minister of State for External Affairs, Natwar Singh, who was also a personal friend, and told rather grimly at 2.30 p.m. on 4 June that the aircraft would leave Bangalore in half an hour. My reaction was one of both anguish and sadness. I informed Natwar Singh that surely the proposed air-drop was a blatant violation of our territorial integrity and interference in our internal affairs and I was saddened by the fact that this step would bring Indo-Sri Lanka relations to the lowest level ever in the long history of its close and cordial relationship”.

Bernard Tilekaratna Hands Over Letter of Protest

“As regards conveying the message to the President, I told Natwar Singh the planes might as well leave as scheduled as it would take me half an hour to reach the Chancery and try to send the message. It was at this point that Natwar Singh offered me his personal hotline through to the Foreign Minister and his surprise was so great that it was my impression that this news was received for the first time. In fact I was asked to immediately hand over a letter of protest which I did in the Minister’s office itself before I returned to the Chancery.”

What Bernard Tilekaratna refers to is of course the infamous air drop operation by India over Jaffna . On June 4th 1987 the Indian Air Force conducted “Operation Poomalai” by which food parcels were dropped over Jaffna in what was described as a humanitarian exercise. It was a blatant violation of Sri Lankan air space. This was in the aftermath of “Operation Liberation” in Vadamaratchy and India claimed overt concern then about starvation in Jaffna. Actually no one was starving in Jaffna then. The whole exercise, beneath the humanitarian facade, was a power projection, intended to drive home a lesson to Colombo.

JR and the “Lakshmana Rekha” Drawn by India

The real situation in Jaffna was distorted to convey an impression that there was starvation warranting the drastic action of violating Lankan air space. So, food parcels were dropped in what was essentially a “demonstration effect” device. President JR Jayewardene realised what was in store if he failed to toe the “Lakshmana Rekha” being drawn by India. So he ‘bowed” to the big neighbour.

The immediate consequence was the accord. Yet, later events proved that JR had only “stooped to conquer”.

Next week the column wiil discuss how JR Jayewardene had the last laugh

D.B.S.Jeyaraj can be reached at [email protected]

16 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

16 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

16 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

16 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

16 Nov 2024 5 hours ago