06 Sep 2013 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

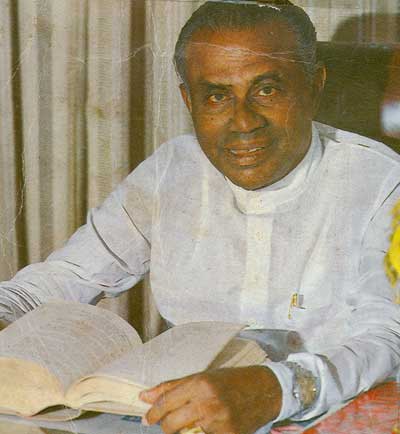

.jpg) The birth centenary of Saumiamoorthy (spelled sometimes as Saumyamoorthy or Saumiyamoorthy)Thondaman was on August 30th.Thondaman was the undisputed “Thalaiver”(leader ) of Sri Lanka’s predominantly Indian Tamil plantation proletariat for several decades. The founder leader of Ceylon Workers Congress (CWC),Sri Lanka’s largest Trade Union in the estate sector , was born in Munapudoor in what was then the Madras Presidency of India during British rule on August 30th 1913.The paternal grandfather of Sri Lanka’s Livestock and Rural Community Development Minister Arumugan Thondaman , died of a myocardial infarction at the Sri Jayewardenepura Hospital in Colombo on October 30th 1999.

The birth centenary of Saumiamoorthy (spelled sometimes as Saumyamoorthy or Saumiyamoorthy)Thondaman was on August 30th.Thondaman was the undisputed “Thalaiver”(leader ) of Sri Lanka’s predominantly Indian Tamil plantation proletariat for several decades. The founder leader of Ceylon Workers Congress (CWC),Sri Lanka’s largest Trade Union in the estate sector , was born in Munapudoor in what was then the Madras Presidency of India during British rule on August 30th 1913.The paternal grandfather of Sri Lanka’s Livestock and Rural Community Development Minister Arumugan Thondaman , died of a myocardial infarction at the Sri Jayewardenepura Hospital in Colombo on October 30th 1999.| Another illustration of his political acumen and tactical shrewdness was revealed to me on the day before his appointment as Minister of Rural Industrial Development in the JR Jayewardene Government. He showed me the list of departments, boards and corporations under the newly created ministry |

| He was in actuality a latter day Moses who led his people from oblivion and irrelevance to equality and self-respect applying Chanakyan methods in a practical sense. I have often compared and contrasted Thondaman with the leaders thrown up by the Sri Lankan Tamils and bemoaned the fact that there were and are no leaders of Thonda’s acumen,sagacity and experience amongst them |

| Thondaman himself was critical of the confrontational tactics of Sri Lankan Tamils, both violent and non-violent. He told me several times that the trouble with the TULF leaders was that they did not know how to negotiate |

| Thondaman was not overtly critical of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) or the armed struggle by Sri Lankan Tamils. His pragmatic proposal that power be handed over to LTTE leader V. Prabakaran for a stipulated period of time without being obligated to face elections was thoroughly misunderstood in the South. |

17 Nov 2024 23 minute ago

16 Nov 2024 5 hours ago

16 Nov 2024 6 hours ago

16 Nov 2024 7 hours ago

16 Nov 2024 7 hours ago