Some moments in the history of a fermenting ‘Divide’

Considering its insecurities, federalism has become an “F- word”:even devolution is being turned into a “dirty” word

By D.B.S.Jeyaraj

(1)(1)(1)(1).jpg) Political developments in Sri Lanka during the post–independence years have devalued the concept of power sharing through the federal idea. Each major ethnicity has viewed the question suspiciously through its particular prism. Sri Lankan Sinhala “patriots” think the introduction of federalism will ultimately lead to division of the Country.Tamil Eelam Tamil “patriots” think federalism is a ruse to weaken Tamil nationalist aspirations for a separate state. The Muslims particularly from the North–East are worried about their place in a federal situation.

Political developments in Sri Lanka during the post–independence years have devalued the concept of power sharing through the federal idea. Each major ethnicity has viewed the question suspiciously through its particular prism. Sri Lankan Sinhala “patriots” think the introduction of federalism will ultimately lead to division of the Country.Tamil Eelam Tamil “patriots” think federalism is a ruse to weaken Tamil nationalist aspirations for a separate state. The Muslims particularly from the North–East are worried about their place in a federal situation.

Against this backdrop of contending insecurities, federalism has become the “F- word” in Lankan politics.Even devolution is being turned into a “dirty” word by some.

The course of contemporary politics in the island has created a situation where federalism or the federal idea is identified with the political aspirations of the Tamils of Sri Lanka. Against that backdrop it is indeed ironic to know that federalism was first introduced to the political discourse of the country by Sinhala political leaders during British rule when Sri Lanka was known as Ceylon.It may also be interesting to note that when federalism as a form of governance was proposed in the pre – independence period by Sinhala leaders there were no takers for it among Tamils.

Post–independence politics however saw a reversal of roles. The demand for federalism began gaining support among Tamils. This resulted in Sinhala leaders losing enthusiasm for the federal idea. Subsequent events saw federalism becoming discredited among Tamils too as secessionism and armed struggle gained dominance.

Those desiring a federal solution feel that unity is possible amidst diversity but those opposing it opine that only “unitary” will bring about unity. What the unity propagandists forget or ignore is that the island’s current avatar as a single state was made possible only by the British colonialists. It was in 1832 that the British unified the Country into modern Ceylon by forging together the Kandyan, Low – Country, and maritime regions into one entity.The existing 32 administrative divisions were compressed into five provinces. Some decades later the five became nine provinces.

The Tamil Congress proposed a “fifty–fifty” representation . Accordingly 50% of seats were to be allocated for the Sinhala majority and 50% for other minority communities including Tamils. But, the Soulbury Commission refused to create an “artificial majority out of a minority”

“Father of Federalism/Federal Idea”

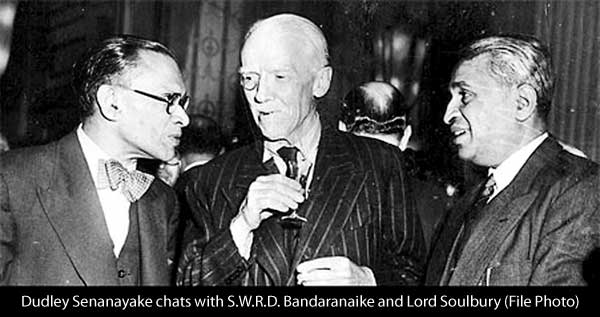

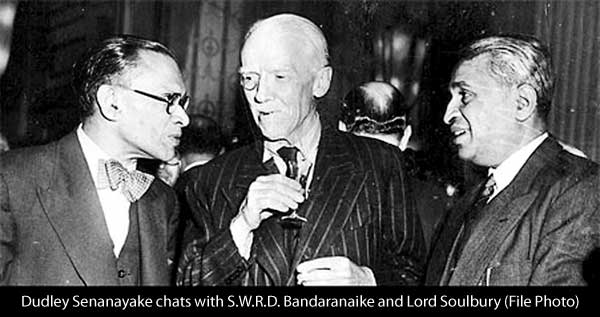

Even as the unified Ceylonese nation began progressing towards self – government under British rule the necessity for some form of de-centralisation and/or devolution was felt. Both de – centralisation and devolution were used interchangeably in those days. The first person of eminence to propose federalism for Ceylon was none other than Solomon West Ridgeway Dias Bandaranaike (SWRDB) whose birthday was yesterday Jan 8th. If the “Lion of Boralugoda” Philip Gunawardena could be described as the “Father of Marxism/Socialism” then the Laird of Horagolla Solomon Bandaranaike could be termed the “Father of Federalism/Federal Idea” in Ceylon/Sri Lanka.

SWRD Bandaranaike returned home in 1925 after pursuing a brilliant academic career at Christ Church College, Oxford. Like many young idealists from countries under colonial bondage , SWRDB too came back with a zealous sense of mission to serve his country and people. While being a member of the Ceylon National Congress Bandaranaike also founded a political party known as the ‘Progressive National Party’ to achieve the goal of political self-government. SWRD Bandaranaike became the leader of the Progressive National Party while C.Ponnambalam of the Jaffna Youth Congress was the Party .

The Oxford returned SWRDB was of the view then that Ceylon should become a federation. The Progressive National Party in its Constitution detailed an outline of the federal system Bandaranaike had in mind. While noting that the three main groups in the country were the Low Country Sinhalese, Up Country Sinhalese and the Tamils, the party constitution wanted the federal system to be based on the nine Provinces with each of the nine Provinces having complete autonomy. There was to be a bicaramel legislature consisting of a “House of Commons “ and “House of Senators”. Bandaranaike’s proposal for a Federal Constitution was supported by all members of the Progressive National Party except one. The solitary dissident was the scholar James T.Rutnam who was Bandaranaike’s close friend and associate.

SWRD Bandaranaike wrote a series of six articles for the “Ceylon Morning Leader” articulating his vision on Federalism. The preliminary article appeared on May 19th 1926. The following excerpt consists of the introductory paragraphs from the preliminary article-

“At a time when the desire for self-government appears to be growing ever stronger, and successive installments of ‘reforms’ seem to bring that goal almost within sight, two problems of vital importance arise, which require careful and earnest thought. The first is the question of Ceylon’s external status, that is what is her position as a nation in relation to other nations. The second is her internal status, the adoption of a form of government which would meet the just requirements of the different sections of her inhabitants.No effort has yet been made seriously to consider these problems, nor indeed in some quarters is it realized that the problem exist at all! There is the usual vague thinking, there are the usual generalizations, to which politicians are only too liable, the catch-words are the bane of politicians all over the world… in Ceylon we find in constant use, such phrases as “co-operation, ” “self-government,” cabinet-government,” without any clear understanding of either what they really involve or whether and to what extent, they are applicable to our own particular difficulties.The writer believes the true solution to the problem mentioned is contained in the federal system and these articles are intended as a General Introduction to the subject”.

Bandaranaike’s advocacy of federalism did not create a major political splash at that time.Only ripples. The federal idea did not evoke a communal or Sinhala backlash then. The strongest critique was not from a Sinhalese but from a Tamil. James T. Rutnam wrote articles in “Ceylon Morning Leader” arguing against the views of his friend SWRD Bandaranaike. James Rutnam was for a unitary constitution.He opposed a Federal constitution saying it would cause disunity among the people.Rutnam opined that the Sinhalese and Tamils would become segregated under a federal constitution. He pointed out that the Muslims, Malays ,Burghers and Europeans would become submerged as they were a scattered minority in all provinces which were dominated by either Sinhalese or Tamils. Rutnam stated that there would be much haggling by each province for greater share of resources. He even predicted that increasing friction among the federal provinces may even lead to secession in the future. It is however interesting that James Rutnam revised his opinion of 1926 thirty years later. He advocated federalism after 1956.

With Tamils enjoying prestigious professions, government jobs and commerce in Sinhala areas, the dominant Tamil elite did not want to be confined to the North and East through federalism

“Federation as the only Solution”

The federal idea when suggested by SWRDB in 1926 was opposed by the Jaffna Students’ Congress later re-named as the Jaffna Youth Congress. Bandaranaike was invited by the Jaffna congress to deliver a lecture to a large audience in Jaffna. SWRDB travelled up to Jaffna and spoke on federalism at a meeting held on July 26th 1926. The well-attended meeting was presided over by Dr.Issac Thambyayah. Young Bandaranaike spoke eloquently on the topic “Federation as the only solution to our political problems”.SWRDB argued that regional autonomy was the ideal way to manage communal differences.The audience was neither impressed nor enamoured by the federalism pitch. Bandaranaike was subjected to a barrage of questions challenging federalism as a valid form of government for the Island. SWRDB answered with great erudition the there were few takers for federalism among Tamils in Jaffna then.Nevertheless SWRD Bandaranaike stood firm saying “A thousand and one objections could be raised against the system, but when the objections are dissipated, I am convinced that some form of Federal Government will be the only solution’.

While the Tamils of Ceylon/Sri Lanka treated the Federal idea as politically untouchable another ethnic sub – group touted federalism as a manthra in the twenties of the twentieth century. Kandyan Sinhala representives comprising mainly of the Radala elite were suspicious of a political system where the numerically larger Low–Country Sinhalese could swamp them. So they went before the Donoughmore Commission in 1927 and proposed a federal Ceylon comprising three units. One for the three Kandyan provinces, one for the four Low – Country provinces and one for the two Tamil provinces of the North and East.

What had happened then was that the political climate of Ceylon/Sri Lanka had undergone transformation with the advent of the Donoughmore Commission. A four member team headed by Lord Donoughmore was appointed by Whitehall to hear representations and propose a new constitutional arrangement for Ceylon. The Donoughmore Commission spent four months in the island from August 18th 1927 to Jan 18th 1928. The commissioners held 34 sittings and interviewed over 140 persons from various delegations. Several petitions and appeals in writing were also accepted. The Donoughmore commission released its report on June 28th 1928. As a result of the Donoughmore report universal suffrage for men and women over 21 years was made possible. Communal representation was abolished and territorial representation was introduced. A legislature known as the State Council was established with 50 elected and 8 appointed representatives in 1931. A board of seven ministries was also set up.

When the Donoughmore Commission was in the country several political groups and organisations representing race,religion, caste and creed made representations. Among these was the Kandyan National Assembly (KNA) consisting of Up- Country Sinhala leaders who had broken away from the Ceylon National Congress in 1925. Their main problem at that time was the large scale migration of low– country Sinhalese into the highland provinces. Leaders of the Kandyan National assembly such as A.Godamune had earlier welcomed the Federalism proposal of SWRD Bandaranaike. Now the Kandyan National Assembly appealed to the Donoughmore Commission for a scheme of three federal units. The first was for the Kandyan Sinhalese of Uva, Sabaragamuwa and Central Provinces. The second was for the Low–Country Sinhalese of Southern,Western, North Western and North Central Provinces. The third was for the Sri Lankan Tamils of the Northern and Eastern Provinces.

Federalism was first introduced by Sinhala political leaders during British rule when Sri Lanka was known as Ceylon

According to the KNA, the Kandyan Sinhalese were a distinct nation.In making this claim before the Donoughmore Commission the Kandyan National Assembly delegation argued thus–“Ours is not a communal claim or a claim for the aggrandisement of a few;it is a claim of a nation to live its own life and realize its own destiny.... We suggest the creation of a federal state as in the United States of America.....A federal system will enable the respective nationals of the several federal states to prevent further inroads into their territories and to build up their own nationalities”.

Sri Lankan Tamils aimed at one third of seats for Tamils and two-thirds for Sinhalese. The Donoughmore Commission rejected such communal representation as a “cancer eating into the body politic”

Kandyan Sinhalese Proposed Federalism

Dr. Rohan Edrisingha in his illuminating essay “Federalism:myths and realities” makes the following observation–“ It is significant to note that long before Tamil political leaders advocated federalism, the young SWRD Bandaranaike in the mid 1920’s and the Kandyan Sinhalese representatives before the Donoughmore Commission in the late 1920’s were advocates of a federal Sri Lanka.The Kandyan Sinhalese proposed a federal Ceylon with 3 provinces including a province for the North-East. In fact it is possible to argue that it was the Kandyan Sinhalese and not the Ceylon Tamils who were not only the champions of a federal Ceylon but also the merger of the North and east. The Kandyan Sinhalese in fact viewed themselves as a nation and many of the documents of the organizations they established to advance their cause used language and arguments similar to Tamil nationalists and Tamil political groups in the more recent past.They were concerned about the influx of Low Country Sinhalese into the Kandyan region”.

It could be seen therefore that federalism was first proposed by Sinhala political leaders. SWRD Bandaranaike the greatest intellectual among Sinhala political leaders of that era espoused some form of federalism as the only solution as far back as 1926. Kandyan Sinhala leaders recommended a federal arrangement of two units for Sinhalese and one unit comprising the North–East for Tamils in 1927. If Sri Lankan Tamil political leaders had availed themselves of the opportunity and demanded that the British grant federalism for the Tamils of the North and East there was every chance that the request might have been acceded to. The Kandyan Sinhala and Sri Lankan Tamil political leaders could have pressurised the Low Country Sinhala leaders in a political pincer. Yet this did not happen. The Sri Lankan Tamil political leaders did not demand federalism or even a separate state while the British were ruling. Instead these demands were raised only after the British left our shores.

The Tamils of Sri Lanka lacked an effective leader when the Donoughmore Commission arrived in 1927. Sir Ponnambalam Arunachalam had passed away in 1924. His elder brother Sir Ponnambalam Ramanathan revived the Tamil League formed by Arunachalam and made representations before the Donoughmore Commission. Other Tamil organisations also followed suit. The Tamil representation spearheaded by Sir Ponnambalam Ramanathan neither sought secession nor federalism. Instead it asked for greater political representation for the Tamils. Ramanathan opposed territorial representation and supported the communal representation principle.

The Tamils did not think of a federal arrangement for the North–East but argued for communal representation based on greater weight for the Tamils. The Sri Lankan Tamils were aiming at seats in the envisaged legislature on a ratio of two to one. They wanted one third of seats to be allocated for the Tamils and two-thirds for the Sinhalese. The Donoughmore Commission rejected communal representation as a “cancer eating into the body politic” and ushered in territorial representation. This provided the Sinhala people a greater advantage in obtaining more representation. A disappointed Ramanathan who was to die in 1930 lamented loudly” Donoughmore means Tamils no more”.Ramanathan’s emerging political successor GG Ponnambalam described the Donoughmore Constitution as a “political windfall” for the Sinhalese.

Another commission to recommend constitutional reform proposals for Ceylon was appointed by Great Britain in 1944. This was headed by Viscount Soulbury and became known as the Soulbury Commission.The premier political organisation of the Sri Lankan Tamils at that time was the All Ceylon Tamil Congress. GG Ponnambalam was the leader of the Tamil Congress then. The secretary was lawyer S.Sivasubramaniam whose son S.Kathiravetpillai was Kopay MP from 1965 to 1981. Among the prominent leaders in the Tamil Congress was SJV Chelvanayagam who later split and formed in 1949 the Ilankai Thamil Arasu Katchi(ITAK) known as the Federal Party.

Balanced Representation Called Fifty–fifty

It is indeed noteworthy that the Tamil political leadership of the pre–Independence period did not campaign for separation or federalism before the Soulbury Commission. They wanted a scheme where the minority community representation was to be given weightage so that the non–Sinhala communities together could counter-balance perceived Sinhala domination. The Tamil Congress fought hard for a scheme of balanced representation popularly called “fifty–fifty”.

According to this proposal, 50% of seats were to be allocated for the Sinhala majority and 50% for all the other minority ethnicities including Tamils.This was rejected by the Soulbury Commission which refused to create an “artificial majority out of a minority” through a balanced representation scheme. Ceylon gained Dominion status in 1947 and full independence from the British in 1948. The British Governor Sir Henry Mason Monck Moore became Governor General and served till 1949. He was succeeded by Soulbury as Governor General.He served till 1954.

Post -independence developments coupled with the wisdom of hindsight suggest that the Sri Lankan Tamils may have missed golden opportunities by not demanding federalism during British rule.One reason for the Tamil leadership not opting for a federal north –east then was due to the fact that the Tamil political hierarchy of that time was essentially composed of the Colombo based elite. With Tamils enjoying a larger proportion in prestigious professions, government jobs and commerce in Sinhala areas, the dominant Tamil elite did not want to be confined to the North and East through federalism. The Tamil leadership perceived the community as being “all – island” rather than “regional” hence the Tamil Congress was named All Ceylon Tamil Congress.Subsequent events proved how short – sighted this pre-independence belief was.

Meanwhile the Sinhala polity underwent a change. There was a closing of ranks between the Low Country and Up Country Sinhalese on the one hand and the Govigama – Karawe elites on another. The Kandyan Sinhala leaders who feared a Low Country Sinhala influx were now besieged by another perceived danger. They feared being inundated by the plantation workers of Indian origin in their midst. Furthermore GG Ponnambalam’s futile efforts to mobilise the minority communities and gang up on the majority community resulted in the Sinhalese defensively forging greater unity among themselves. Independent Ceylon’s first prime minister DS Senanayake was a Low Country Sinhalese. His govt. de – citizenised and disenfranchised the Tamils of Indian origin after Independence. This resulted in Kandyan Sinhala political representation increasing. Gradually the Low Country – Up Country Sinhala differences began diminishing. Nowadays most Kandyan Sinhalese would be horrified to hear that their leaders at one time had imagined themselves to be a separate nation and had advocated a federal arrangement that included a merged unit for the North and East.

As for SWRD Bandaranaike the original proponent of federalism his political journey too had many vicissitudes. As Local govt minister during State Council days SWRDB moved away from federalism to de-centralisation.It must be noted that there was really no antipathy towards federalism at that time.It was more a case of apathy and disinterest. SWRD himself had great political ambition and sought to build up his base through the Sinhala Maha Sabha and by re-structuring and enhancing the local govt system.So he wanted to re-vamp the existing local govt system and provide greater autonomy through de-centralisation.

SWRD envisaged the province as the unit of greater local authority. He wanted to set up provincial councils.The local government ministry’s executive committee released a report advocating more powers to the envisaged councils. In 1940 RSS Gunawardena introduced a motion in the State Council proposing the setting up of provincial councils. The State Council approved it but for some inexplicable reason SWRD did not proceed further and present a Bill in the State Council during its tenure.

Bandaranaike Proposed Provincial Councils

Bandaranaike was the local government minister in Independent Ceylon’s first Cabinet under DS Senanayake.It is said that he tried to revive his provincial council formulation again as a means to bring government closer to the people. But his Cabinet colleagues enjoying power as full – fledged ministers were reluctant to dilute or reduce their newly gained authority. So SWRD could not go through with his plans. This was indeed a great pity because the provincial councils proposed by Bandaranaike could have been set up without much problem then as the ethnic dimension was not prevalent in this sphere at that time.

In 1951 Bandaranaike crossed over to the opposition and founded the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP). Sadly SWRDB saw a shortcut to power by pandering to communalism. The ‘Sinhala- only’ wave saw Bandaranaike becoming prime minister in 1956. In fairness to Bandaranaike he did try to incorporate provisions accommodating Tamil grievances in the Official languages bill. But the hardliners who brought him to power did not permit it. Likewise SWRD revived his pet project of regional autonomy by trying to set up up regional councils. Again his moves were aborted through hard- line opposition.

While Bandaranaike and the Kandyan Sinhalese moved away from the federal ideas another strand of Tamil opinion began moving towards federalism.There was now a new phenomenon on the Tamil political horizon. The main Tamil party the All Ceylon Tamil Congress had split and the breakaway group had formed a new party. There was a clash between GG Ponnambalam the leader of the Tamil Congress and his deputy SJV Chelvanayagam. G.G. as he was generally known, was seen as a pragmatic politician by his supporters After full independence dawned Ponnambalam revised his approach. With balanced representation an impossibility, GG now articulated the concept of “responsive cooperation”.

Ponnambalam opted to join the DS. Senanayake Cabinet. The price he paid for that was the stigma of betraying the Up Country Tamils who were deprived of citizenship and franchise by the UNP regime. GGP became the industries and fisheries minister and established many factories and fisheries harbours in the North – East.

But some of his deputies like SJV Chelvanayagam, C. Vanniyasingham and EMV Naganathan rebelled against Ponnambalam. They broke away and formed a new party. It was called the Ilankai Thamil Arasu Katchi (ITAK) in Tamil. Its English translation should have been Ceylon Tamil State Party but instead it was called Federal Party (FP). The new party wanted an autonomous Tamil state comprising the Tamil dominated Northern and the Tamil – majority Eastern Provinces within a united Ceylon.

The advent of the ITAK was a watershed in Ceylon politics as it was the first Tamil political party to incorporate the Federal idea as its main ideology and goal. Unlike SWRD who emphasised regional autonomy for good governance the FP wanted federalism to protect Tamil interests and achieve ethnic harmony. Unfortunately there was a hiatus between precept and practice. The federal idea as promoted by the ITAK was embroiled in controversy . It was misrepresented, misunderstood and therefore much maligned and much hated.

Opposition to Federalism From Tamil Congress

Initially the opposition to federalism came from the Tamil Congress itself. With the ITAK calling Ponnambalam a traitor for accepting a cabinet portfolio the Congressmen hit back by depicting the federal idea wrongly. Even before Sinhala politicians started distorting the meaning of federalism as secessionism the Tamil Congress began doing so. The Tamil voters were “terrorised” by the propaganda that federalism meant a break with the rest of the Country and that the Tamil businessmen and govt servants in the South would have to return. “The Yal Devi train won’t run that side of Elephant Pass ” was one such ominous threat.

The ITAK wanted a federal union between the Tamil autonomous Tamil state and the residual Sinhala state. This demand too was ridiculed by GG Ponnambalam who pointed out that such union entailed consent by both parties. “Are the Sinhalese prepared for federalism?” he queried. Doubts were also raised whether Eastern Province Tamils, Muslims and Wanni Tamils were ready for federalism. The plantation Tamils and Tamil leftists too were not receptive. The Communist Party later advocated regional autonomy.

The newly formed ITAK won only Trincomalee and Kopay in the 1952 parliamentary elections. Even there the personal popularity of Rajavarothayam and Vanniyasingham had more to do with victory than the federal idea. Other ITAK leaders like Chelvanayagam, Naganathan, Amirthalingam,Navaratnam, Arunasalam etc lost.The Tamil voters had overwhelmingly rejected federalism at the polls. The idea of power sharing at the centre through cabinet portfolios seemed more lucrative than sharing power at the periphery through federalism.

The 1952 – 56 years saw a sea of change in Sinhala and Tamil politics. The SLFP began raising the communal cry and advocating Sinhala as the sole official language. This in turn created insecurity in Tamil areas. The ITAK vowed to resist Sinhala imposition and began mobilising support. In this raucous atmosphere saner voices calling for parity of status like the LSSP were shouted down. Also GG Ponnambalam lost prestige after he was “fired” as cabinet minister by Sir John Kotelawela who became premier in 1953.

Interestingly the federal idea was downplayed by the ITAK during these years. It was the language issue that galvanised Tamil voters. The ITAK retained its demand for an autonomous state of both provinces but in practice did not emphasise it too much. Instead the ITAK projected an impression that it would not object to district based autonomous units being set up. In the fifties of the last century there were only three districts in the North and two in the East.The present Jaffna and Kilinochchi districts formed the Jaffna District. Vavuniya and Mullaithivu Districts were one called Vavuniya. Mannar was the third. In the East the present Batticaloa and Amparai Districts formed one Batticaloa District. Trincomalee was the other.

Embracing Muslims as ‘Tamil- Speaking People’

Chelvanayagam’s new approach was a recognition of regional and sub – national differences within the North – East. The district-based units would lessen fears among non – Jaffna Tamils as well as the Muslims it was felt. The ITAK adopted an inclusive approach towards the Muslims by embracing them under the “Tamil- speaking people” concept. The North – East was the traditional homelands of the Tamils and Muslims it was argued. If Sinhala became the sole official language the counterpoint to it would be the setting up of a Tamil “linguistic” region comprising the North and East.

The 1956 election results saw an ethnic polarisation with the ITAK winning most seats in the Tamil areas and the MEP – SLFP – Bhasa Peramuna combine sweeping polls in the Sinhala areas. Political violence set in when Govt sponsored mobs assaulted Tamil Satyagrahis protesting the imposition of Sinhala as the only official language. Violence also spread in the East where Tamil agriculturists were driven away from lands in newly set up irrigation schemes. This led to a situation where the ITAK re- asserted its demand for an autonomous region of both provinces.

Once again , in fairness to Bandaranaike, it must be said that he tried to resolve the political conflict by trying to address Tamil grievances. He promoted dialogue with the ITAK and tried to arrive at an understanding with Chelvanayagam. This included provisions for usage of Tamil language, preferential policies in land alienation and above a scheme to establish regional autonomy. For this Bandaranaike signed a pact with Chelvanayagam called the Banda – Chelva Pact. Subsequently legislation to set up regional councils was introduced.

Despite his good intentions Bandaranaike found it impossible to honour the pact in practice. The genie he had released from the bottle refused to go back in. The communal forces unleashed by SWRD in his bid for power became uncontrollable. Bandaranaike described by Tarzie Vitachi as “weak and vacillating” went back on his word in deference to the forces that installed him in power. Ultimately those forces destroyed him.

D.B.S.Jeyaraj can be reached at dbs [email protected]

(1)(1)(1)(1).jpg) Political developments in Sri Lanka during the post–independence years have devalued the concept of power sharing through the federal idea. Each major ethnicity has viewed the question suspiciously through its particular prism. Sri Lankan Sinhala “patriots” think the introduction of federalism will ultimately lead to division of the Country.Tamil Eelam Tamil “patriots” think federalism is a ruse to weaken Tamil nationalist aspirations for a separate state. The Muslims particularly from the North–East are worried about their place in a federal situation.

Political developments in Sri Lanka during the post–independence years have devalued the concept of power sharing through the federal idea. Each major ethnicity has viewed the question suspiciously through its particular prism. Sri Lankan Sinhala “patriots” think the introduction of federalism will ultimately lead to division of the Country.Tamil Eelam Tamil “patriots” think federalism is a ruse to weaken Tamil nationalist aspirations for a separate state. The Muslims particularly from the North–East are worried about their place in a federal situation.