27 Jul 2012 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By D.B.S.JEYARAJ

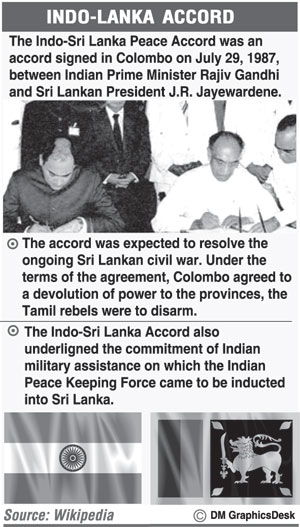

By D.B.S.JEYARAJ Generally Countries act in their own self – interest but often attribute lofty motives for such actions. In the case of India vis a vis Sri Lanka there were three reasons for its conduct.

Generally Countries act in their own self – interest but often attribute lofty motives for such actions. In the case of India vis a vis Sri Lanka there were three reasons for its conduct.

HORIZONS

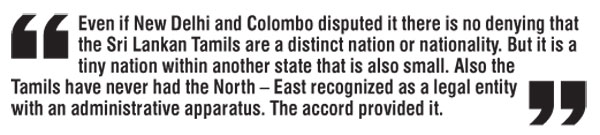

HORIZONS The Indo – Lanka accord acknowledged for the first time that “Sri Lanka is a multi ethnic and multi – lingual plural society consisting inter – alia of Sinhalese, Tamils, Muslims (Moors) and Burghers”.

The Indo – Lanka accord acknowledged for the first time that “Sri Lanka is a multi ethnic and multi – lingual plural society consisting inter – alia of Sinhalese, Tamils, Muslims (Moors) and Burghers”.

But such hopes turned into dupes. The Supreme Court ruled that the merger itself was not done legally. It did not rule out such a merger being validated through appropriate procedures.

But such hopes turned into dupes. The Supreme Court ruled that the merger itself was not done legally. It did not rule out such a merger being validated through appropriate procedures.

17 Nov 2024 24 minute ago

17 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

16 Nov 2024 8 hours ago

16 Nov 2024 9 hours ago

16 Nov 2024 16 Nov 2024