19 Feb 2020 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

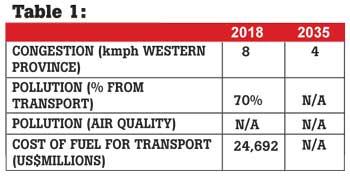

Managing the mobility of people and goods is one of the toughest environmental and social challenges that countries face. Sri Lanka is facing a rapid rise in road congestion and air pollution. With escalating numbers of new vehicles being registered and 70 percent of air pollution being attributed to motor vehicles, it is clear that we need to adopt a long-term perspective, which focuses on sustainable mobility.

Managing the mobility of people and goods is one of the toughest environmental and social challenges that countries face. Sri Lanka is facing a rapid rise in road congestion and air pollution. With escalating numbers of new vehicles being registered and 70 percent of air pollution being attributed to motor vehicles, it is clear that we need to adopt a long-term perspective, which focuses on sustainable mobility.

University of Moratuwa Transport and Logistics Management Department Head Professor Amal Kumarage has gone on record stating that the economic cost of the present congestion is Rs.397 billion annually.

The purpose of this article is to argue that Sri Lanka must use policy to drive the swift and smooth adoption of sustainable mobility in order to solve the issues of congestion, pollution and the high expenditure on fuel (Table 1).

The purpose of this article is to argue that Sri Lanka must use policy to drive the swift and smooth adoption of sustainable mobility in order to solve the issues of congestion, pollution and the high expenditure on fuel (Table 1).

Congestion and air pollution

How serious is the problem? As a developing country, Sri Lanka is facing heightened urbanisation, which increases the need for mobility. The lack of comfort, safety and ride quality in public transportation modes have increased the number of private vehicles on roads.

Travel speeds within the Colombo metropolitan area have gone down from 17kmph in 2017 to 8kmph in 2020 and are projected to go down further to 4kmph in 2035.

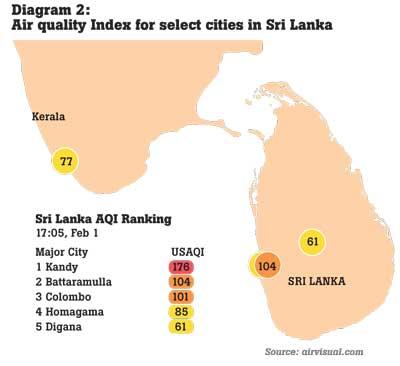

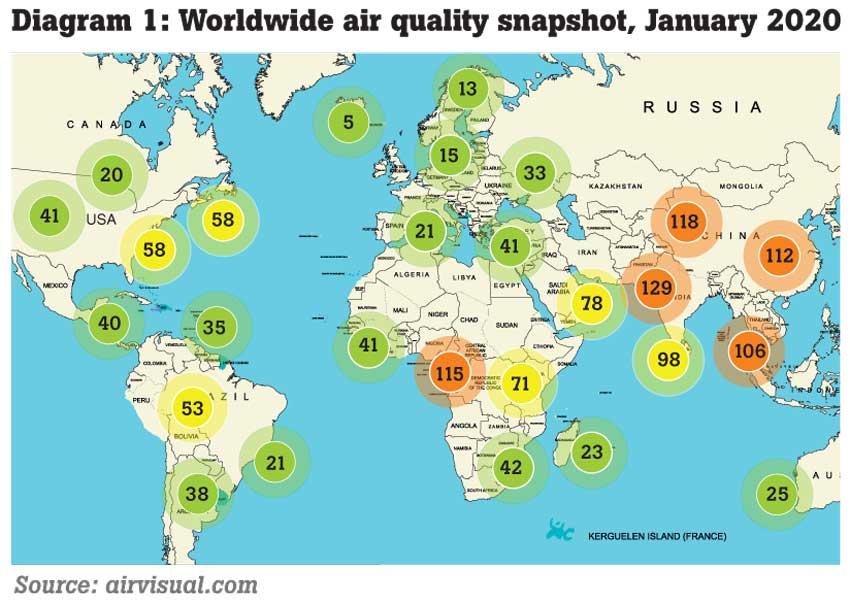

The air quality in Kandy and Colombo fall into the ‘Unhealthy’ category and have led to warnings being issued (Diagram 2). As congestions build, these figures are only going to get worse.

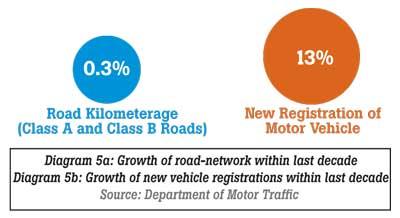

The road network expansion during the last decade has been a mere 0.3 percent, whereas within this time, the number of new motor vehicle registrations in the country has disproportionately increased (Diagram 5a and 5b).

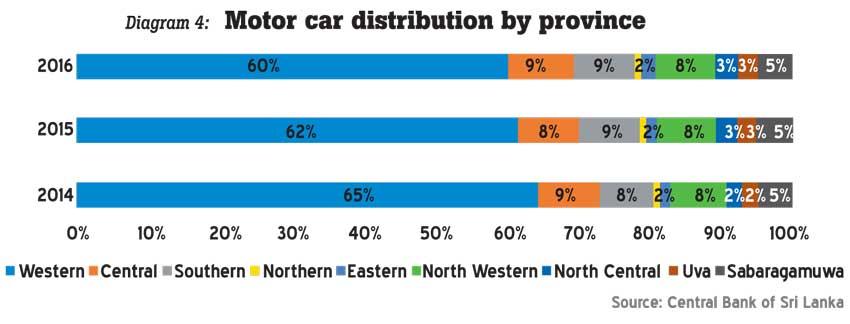

This inequality accordingly brings more congestion to the existing roads. The overwhelming majority of vehicles seem to be concentrated within the Western province (Diagram 6).

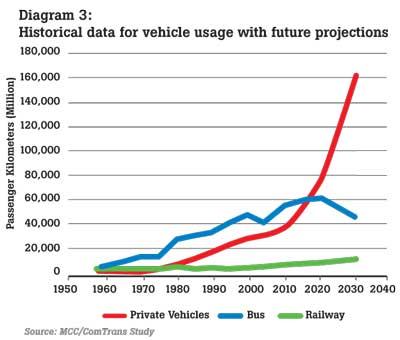

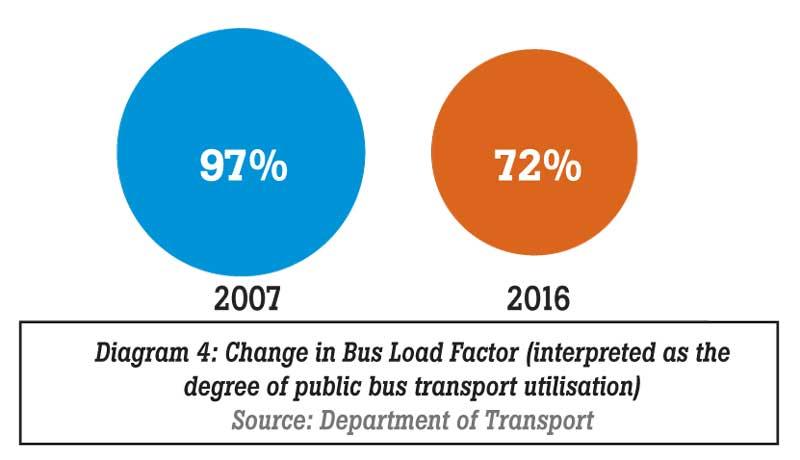

Bus load factors have gone down from 97 percent in 2007 to 72 percent in 2016. Public transport has failed to provide a viable service to commuters, thus reducing its popularity and utilisation (Diagram 4). They have therefore, sought to supplement and resolve their mobility needs through the purchase of private vehicles. The trend seems to be increasing and consequences of it are the various economic and environmental challenges we are looking at today (Diagram 3).

Sustainable mobility and Sri Lanka

What is sustainable mobility? Sustainable mobility is defined as the movement of people and goods with a minimum impact on the environment.

Apart from being the major source of pollution, the import of fossil fuel for transport cost the Sri Lankan government US $ 2.9 billion in 2018 (CBSL report). This accounts for 19 percent of total government imports (2018).

Therefore, in order to introduce sustainable mobility to Sri Lanka, the government needs to look at:

1. Use of renewable energy

2. Use of electric vehicles

3. Explore the use of shared mobility

Renewable energy

The sources of renewable energy are primarily solar and wind. The annual energy consumption globally is equal to the amount of solar energy that hits the Earth’s surface within a few hours. Today, with the increasing acceptance of solar for energy generation and the significant drop in lithium ion battery cost, we can store this energy more affordably. Our tropical island nation has the solar availability to tap into and significantly capture this energy.

Electric vehicles

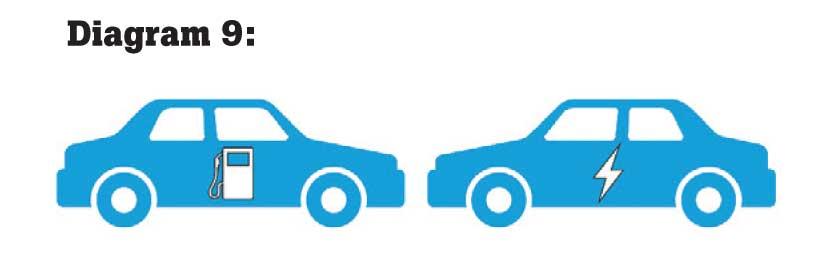

Electric vehicles (EVs) are propelled by electric batteries that store energy to drive a motor. They have zero tailpipe emission and approximately 20 moving parts, which are highly efficient, compared to around 20,000 in a conventional vehicle. Sri Lanka is a small island and as a result, electric mobility options become feasible with the present level of technology.

The longest distance between two points within Sri Lanka is 530km (Dondra in the south to Point Pedro in the north). This journey is not an impossibility in terms of range with today’s electric vehicle technology and the visible trend towards increased capability.

Shared

Sharing a journey to reduce running costs has been an age-old practice. Uber was one of the first to convert this to a successful business, which is disrupting private ownership of vehicles. In Sri Lanka, Uber and PickMe augment the taxi service, offering cheaper, faster and more convenient rides and booking options.

Unlike in other countries, where the owners of private vehicles offer rides to customers to supplement the cost of their own journey, in Sri Lanka, most Uber/Pick me drivers work full time.

Driving sustainable mobility

By bringing in a few simple controls such as reduced parking, congestion charging during peak hours and zonal charging, the number of vehicles coming in to the city could possibly be reduced. This would also encourage the adoption of shared mobility.

By encouraging the purchase and use of EVs through preferential duty and tax rates, exemptions on city entry charges, preferred parking and a network of charging points throughout the country for electric vehicles, the pollution levels could be brought down.

Further, by encouraging the use of solar and the storage of solar energy, the pollution can be brought down to an even greater extent (Diagram 8).

ACES and future mobility

The acronym ACES stands for autonomous, connected, electric and shared and is the platform that will facilitate future mobility. This is not a concept of tomorrow; many European countries are currently in the phase of integrating ACES.

Autonomous vehicles have been tested since the 1920s and the first truly autonomous car was designed by the Carnegie Mellon University’s Navlab in 1980. In 2017, Waymo announced that it had tested a fully autonomous car on public roads for 10 million miles and subsequently in 2018, this company commercialised a fully automated

taxi service.

An autonomous vehicle could be defined as one that is bidirectionally connected to a host of devices outside of the vehicle. This also means that the vehicle can transmit details on its location, speed and other meaningful information about its surroundings as well as who is in it. This issue does bring data privacy into question and hence it will be a significant component of the ACES ecosystem’s legislation.

The ‘E’ stands for electric. The electric car is considered a zero-pollution transport tool. There is some pollution in the manufacturing of the car but not in its propulsion. In the Sri Lankan context, a common argument against the zero-emission factor of electric cars is that the national grid uses fossil fuels and hence when a car is charged by the grid, it causes pollution.

However, a counter argument would be that the pollution caused by a pool of cars being charged by the grid is less than that of the same number of internal combustion engine (ICE) cars.

An electric vehicle has around 20 moving parts, compared to an ICE vehicle having over 20,000. This makes the maintenance cost of an EV much less than an ICE and this benefit is compounded by the fact that the EV is estimated to last much longer (Diagram 9).

It is widely quoted that transportation devices are only used 7 percent of the day, therefore a shared device will greatly enhance efficiency and utilisation.

Shared mobility is already widely used in Europe and America. A definition of this concept is that it allows commuters to use transportation devices on an ‘as needed’ basis without ownership. Business models such as Uber and Airbnb are examples of how extra capacity is used to give a financial benefit to the user or asset owner.

All transport experts agree that transportation will be ACES and the only point of contention is regarding the time it will take before ACES

is commonplace.

MaaS

The other acronym associated with future mobility is ‘mobility as a service’ (MaaS). MaaS aims to provide an alternative to the use of a private vehicle by giving commuters access to various forms of transport solutions in one space with a single payment option.

MaaS makes transport more convenient, more sustainable, reduces congestion and can possibly make travelling cheaper for the commuter. There are many examples of such platforms already in use in Europe.

The concept of MaaS is even wider than what Diagram 10 shows. The platform can offer every mobility solution fathomable, including parking, ride hailing, ride sharing, using land rail, sea and underground transport services. The platform additionally allows the commuter to switch between transport services as required.

For example, a commuter on a MaaS app, who is driving could be advised to park his car at a tube station and take a tube to reach his destination faster. He could also book his parking place and pay for it via the platform itself.

ACES and MaaS in Sri Lanka

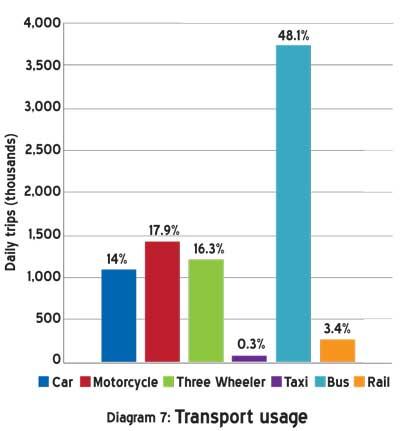

Japan and Singapore are examples of countries in Asia that provided commuters an exceptional level of public transport through the rail and tube. These utilities were constructed at a significant capital cost. The quality of public transport in Sri Lanka is far below this standard and for that very reason private ownership has been on the rise. However, as shown in Diagram 7, over 50 percent of Sri Lanka’s population still uses mass transport.

Bringing the main bus and train services onto a digital platform will enable commuters to use these services and integrate them into door-to-door mobility solutions such as taxis. This platform can support the development of more shared mobility solutions, working together with the mass transport sector.

The reason for private mobility solutions to grow exponentially is the low level of service and customer experience that mass transport solutions give the customer. Whilst MaaS is not going to solve the qualitative problems of mass transport, it will undoubtedly provide a platform that can help significantly enhance convenience and overall customer experience.

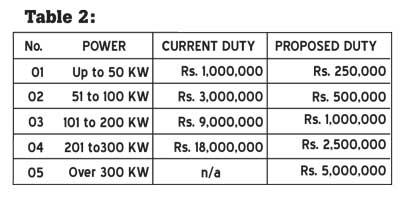

Regarding the problems in Sri Lanka, we have to solve the issues of pollution, congestion and the cost of fuel imports. In the medium term, our public transport needs upgrading. Until this is done, MaaS (and subsequently ACES) can present an immediate solution that is not highly capital-intensive (Table 2).

India currently has 40 ‘apps’ and have brought public transport onto a digital platform. This and the success shown with a platform implemented in the Indian city of Mysore implies that that is applicable to Sri Lanka as well.

The digital platform could make public transport more acceptable to the average Sri Lankan commuter and it could induce more commuters to use the service. Finally, the upgrading and electrification of the service would be the long-term solution.

MaaS will pave the way for the adoption of ACES in Sri Lanka.

Accelerating MaaS, ACES in SL with 3 Ps Policy

Whilst sun and size facilitate the rapid adoption of MaaS in Sri Lanka, the real driver is ‘policy’. The policy requirement to drive the change from ownership to shared electric mobility is quite simple. Firstly, there needs to be a significant reduction in the duty applicable to electric vehicles. A suggested duty regime is given below:

Tourism could lead the way to changing from ICE to future mobility. The industry is in need of a fleet upgrade. Further, the present level of excessive duty on the industry for their tourism-related fleet finally feeds into cost for the tourist and negatively impacts Sri Lankan competitiveness.

If the industry could be granted a duty-free import facility for their fleet, as long as they imported EVs and if it were made mandatory for hotels to provide EV charging, this could immediately provide an EV network.

City entry charges and congestion charges need to be implemented at a high rate on private vehicles and at a still higher (or even an exorbitant) rate on ICE vehicles. One could even ban ICEs from entering areas of the city and these would then be ‘zero-emission’ zones.

Government vehicles could be sold and government officials given travel vouchers.

The general principle behind these simple policies is to strongly discourage private ownership as well as the purchase of ICEs while simultaneously encouraging people to buy EVs and to use shared mobility solutions.

Many countries striving to promote shared mobility have made public parking scarce and again a differential scarcity for ICE vs EVs could promote the underlying pro-EV policy.

Platform

The second ‘P’ needed to promote shared mobility is the digital platform discussed under MaaS. It is interesting to note that no less than 40 mobility service apps are already operational in India. Mysore has implemented a platform and brought the city buses on to it and this platform is working very successfully.

Product

The third ‘P’ is product. The world is about to be bombarded with a host of EV products. All major automotive manufacturers are including many EV models into their range. On top of this, several technology firms and start-ups are getting into the transport and mobility business with numerous product and service offerings.

Once the ‘policy’ and ‘platform’ are in place, it is anticipated that the products will soon follow. Tesla just launched its model 3 priced at US $ 35,000. This is leading all other manufacturers to bring down the price of their offerings. With the continuous reduction in the cost of batteries, vehicle prices will reduce. Adding this to the adoption of autonomous vehicles, costs will drop even further as efficiency and utilisation are enhanced. Numerous new companies are getting into the transportation space. All these products can come to Sri Lanka if the policy and platform are in place to support sustainable mobility (Diagram 11).

Conclusion

Sri Lanka desperately needs to resolve its problems of congestion, pollution and declining air quality. Concurrently, the country needs better intra-city public transport. The policy recommendations made in this article could be the backbone of both a short-term and long-term solution to these problems.

Solving these problems, using the means discussed in this article could reduce the economic loss from congestion and pollution by at least 50 percent before 2025.

(Sheran Fernando is a Co-Founder of Innosolve Lanka (Pvt.) Ltd, a start-up dedicated to introducing sustainable mobility solutions in Sri Lanka. He is an economist by training, with wide commercial experience, including 20 years in the automotive industry. He belongs to the alumni of Harvard Business School (OPM53))

16 Nov 2024 40 minute ago

16 Nov 2024 55 minute ago

16 Nov 2024 1 hours ago

16 Nov 2024 1 hours ago

16 Nov 2024 1 hours ago