27 Nov 2020 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The 2021 Budget Speech delivered recently in Parliament by Sri Lanka’s Prime Minister cum Finance Minister outlines a development strategy, couched in the rubric ‘Vistas of Prosperity and Splendour’, for elevating a COVID-19 shattered economy. In many respects, the speech is heroic as it attempts to chart a course for making Sri Lanka a self-reliant, prosperous nation in the midst of a global pandemic.

The policy initiatives and incentives for promoting import substitution in a wide range of goods and services as well as exports of selected commodities and the public investment programme for improving physical and social infrastructure facilities in rural areas indicate that economic and social development of the countryside will be given top priority in the years to come.

The focus on agriculture-driven rural development is commendable, as it is consistent with the goal of growth with distributive equity of income. Be that as it may, the budget speech is a key government policy document and even though eloquently composed, should not escape the rigors of close scrutiny. Here are some issues that merit critical attention.

Budget deficit

The Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL), International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank (WB) and Asian Development Bank (ADB) differ sharply in their GDP growth estimates for this island (currently engulfed by a second COVID-19 wave) in 2020.

The CBSL estimate is -1.7 percent, compared with the other three estimates of -4.6 percent, -6.7 percent and -5.5 percent, respectively. The budget deficit to GDP ratio in 2020, as estimated by the government, is 7.9 percent. This would jump to around 10.9 percent, if we assume a GDP growth rate of approximately -4.6 percent, the average of the above four estimates.

The projected budget deficit to GDP ratio in 2021 is 8.9 percent, which is 1.0 percent higher than the 2020 estimate, on account of the pressing need to rebuild the shattered economy through disproportionately large expenditure outlays. The actual ratio is likely to be much higher than 8.9 percent, if the government underperforms in respect of revenue and overperforms in respect of expenditure.

This is usually the case in a normal year but given the severely depressed state of the economy, we could expect even a greater divergence between the target ratio and actual performance in 2021. This will only serve to aggravate the existing fiscal imbalances and drive the country deeper into debt.

The backbone of the Sri Lankan economy is the small and medium enterprise (SME) sector, which has been devastated by the COVID-19 pandemic. A disappointing feature of key expenditure programmes identified for 2021 is the absence of a fiscal stimulus package for reviving this sector. In the absence of such a programme, one wonders how the government is going to achieve an economic transformation of the rural areas.

Indeed, a peculiar feature of Budget 2021 is that it is for all intents and purposes a ‘normal’ budget, with the usual array of incentives, subsidies, tax holidays and extravagant projects, even though the current social and economic circumstances are

highly ‘abnormal’.

What’s missing are bold macroeconomic adjustments such as tax increases and prioritisation of cost-effective expenditures to cope with the havoc wreaked by COVID-19 in all sectors of the economy and tough institutional reforms such as the restructuring of state-owned enterprises that are incurring huge losses year after year and have to be subsidised by the Treasury to remain in business.

Global competitiveness

One of the main reasons why the Sri Lankan economy is stuck in a low growth trajectory is that it is not as globally competitive as the more prosperous Asian nations. Countries that make efficient utilisation of land, water, labour, capital, time and knowledge and place considerable emphasis on value addition in the agricultural, manufacturing and service sectors, are globally competitive, whereas those wallowing in the vicious circle of low productivity and low growth (like Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Pakistan) are not.

If countries like Taiwan, South Korea, Thailand, Malaysia and Vietnam are wealthy, it is because their export-led economies are on the whole globally competitive. In 2019, Malaysia’s per capita exports of goods and services amounted to US $ 7,300, compared with Sri Lanka’s paltry US $ 890.

Will the development strategy outlined in the 2021 Budget Speech improve the global competitiveness of the Sri Lankan economy? The answer is that this is an unlikely prospect since focus is more on import substitution than on export promotion. This approach is more likely to dampen than to improve Sri Lanka’s global competiveness. A few examples will suffice to illustrate this point.

(i) The plantation management companies have been instructed by the government to pay a daily wage of Rs.1,000 to plantation workers. If the impact of this policy on global competiveness is negative (vis-a-vis higher production costs per unit of output), it could lead to a significant decline in the export of plantation crops, especially tea, the island’s second largest export earner.

(ii) The trade policy outlined in the budget speech, by and large, is protectionist. In other words, any goods or raw materials that are currently produced or have the potential to be produced in Sri Lanka will be protected through various measures, including outright import bans, import restrictions, import licensing requirements and high tariff walls. A similar approach, compounded by a plethora of government permits and controls (not to mention severe administrative bottlenecks), was adopted by the SLFP-LSSP-CP coalition government of 1970-1977 to promote import substitution without any thought given to global competiveness and it produced disastrous results. No doubt it was the volatile mixture of low growth, rampant inflation, high unemployment, widespread poverty and malnutrition and massive social discontent that gave the UNP a landslide victory in mid-1977. We should note that many Asian countries have prospered through economic liberalisation whereas none has prospered through protectionism to date.

(iii) A protectionist trade policy tends to raise food prices sharply, due to the obsession of the state with attaining food self-sufficiency at any cost. For instance, due to the import ban on turmeric (a healthy spice with strong anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant properties consumed by practically every household in the island), the retail price has gone through the roof. With the COVID-19 second wave sweeping through the island, creating a massive artificial shortage of a vital health food simply doesn’t make sense. In the absence of competition, there is no pressure on producers to innovate with the result that utilisation of scarce resources becomes more and more inefficient. In other words, a gradual decline in productivity occurs. Productivity and price per unit of output are inversely related. When the general food price level keeps rising due to declining productivity, consumers are forced to spend more and more money on food and less and less on manufactured goods. When consumer demand for manufactured goods falls, it inhibits growth of rural industries and related services. Moreover, surplus labour remains trapped in the agricultural sector, thereby compounding the problems of rural poverty, under-employment and low productivity. This is what happened prior to 1977 under the tutelage of the inward-looking coalition government. If the current government does not shed its inward-looking stance, there is a high probability that history will repeat itself a few years down the road.

Macroeconomic stability and economic growth

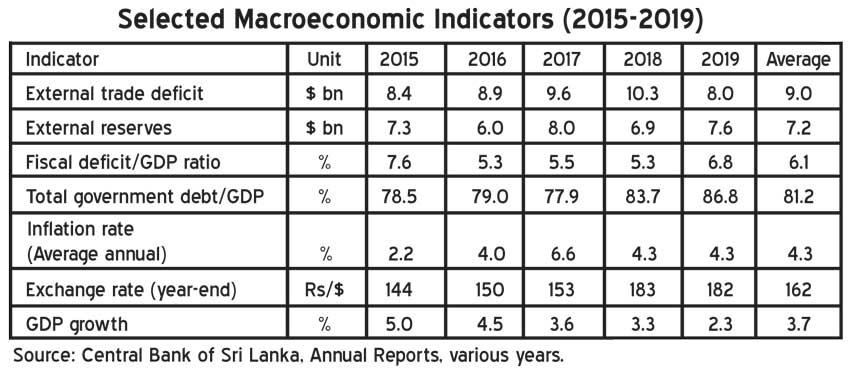

The budget speech, while recognising that inclusive economic growth is the engine of poverty reduction, fails to mention the key role that macroeconomic stability plays in fostering growth. A country that is in a state of macroeconomic instability is generally characterised by the following features: large external trade deficits; low levels of external reserves; large fiscal deficits; high and continually rising levels of government debt; high inflation rates; a weak currency with a tendency to continually depreciate against the US dollar and sluggish or declining GDP growth. As shown in the table, the Sri Lankan economy exhibits all these features with the exception of a high inflation rate.

The high government debt to GDP ratio (87 percent in 2019 and probably exceeding 100 percent in 2020) is extremely worrisome, as it is a major source of macroeconomic instability. In the absence of prudent fiscal management, government could well fall into a debt trap from which it will find it exceedingly difficult to extricate itself. This will spell disaster for the economy and the country as a whole.

If there are three fundamental lessons to be learnt from China, which is showing positive GDP growth despite the COVID-19 pandemic, the first is that rapid and sustainable GDP growth will not occur in the absence of continuous technological change; the second is that technological change at the rate and level required to accelerate GDP growth depends critically on large, foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows to key sectors of the economy such as agro-processing, information technology and communication, health and education, manufacturing, construction and transportation and the third is that these inflows will not occur in the absence of macroeconomic stability.

It was largely due to macroeconomic instability and the climate of political and economic uncertainty that FDI inflows to Sri Lanka averaged only US $ 1.0 billion per annum during the past five years

(2015-2019).

“Macroeconomic stability is the cornerstone of any successful effort to increase private sector development and economic growth … Without macroeconomic stability, domestic and foreign investors will stay away and resources will be diverted elsewhere” (IMF, Macroeconomic Policy and Poverty Reduction, 2001).

Given the paramount importance of achieving macroeconomic stability and creating a buoyant, globally competitive economy (as discussed above), the question arises as to whether the inward-looking narrative framing Budget 2021 makes sense.

(Seneka Abeyratne, a retired economist/international consultant to ADB/Manila, can be reached via

[email protected])

24 Dec 2024 18 minute ago

24 Dec 2024 40 minute ago

24 Dec 2024 2 hours ago

24 Dec 2024 3 hours ago

24 Dec 2024 3 hours ago