23 Apr 2018 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Lack of English proficiency is a key constraint affecting the employability of the Sri Lankan graduates in the private sector, according to a recent Labour Demand Survey conducted by the Census and Statistics Department.

Lack of English proficiency is a key constraint affecting the employability of the Sri Lankan graduates in the private sector, according to a recent Labour Demand Survey conducted by the Census and Statistics Department.

Although teaching English as a second language to all school children has been a key social policy of successive governments of Sri Lanka since the early 1950s, the Census of Population and Housing data indicates that English literacy is just 22 percent among Sri Lanka’s population above 15 years of age.

Recognising the critical need for strong English language skills in today’s context of increasing globalisation, technological advancement and a modernized labour market, the recent government policy has devoted attention to addressing the persistent gaps in English education; the 2018 budget allocated Rs.50 million for the establishment of a centre for training English teachers, while the previous government announced targets to double the number of English teachers over the 2011-2020 period.

Yet, are such policies the need of the hour? Based on an analysis of the available data, this article argues that what is more important is to address the disparities in access to quality English education, rather than solely focusing on improving the overall quality.

Unequal student outcomes

Since 2003, the National Educational Research Centre, based at the Colombo University, has administered tests in the first language (Sinhala and Tamil), mathematics, science and English to grade four and grade eight students in a representative sample of schools across the country.

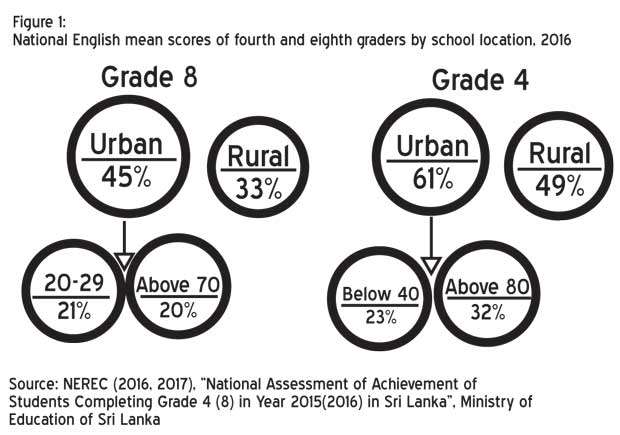

The latest assessments from 2015 and 2016 reveal low national English mean scores of 54 percent and 36 percent among grade four and eight students, respectively. Even more concerning is that these national averages mask a considerable variation in scores both between and within schools.

As Figure 1 shows, both the fourth and eighth graders in urban schools outperform their rural school counterparts by significant margins. Further, there are wide disparities in scores within schools, particularly in urban schools. For instance, while 21 percent of eighth graders in urban schools scored within the 20—29 mark range, another 20 percent scored above 70. Among the fourth graders, 23 percent scored below the pass mark of 40 percent, while 32 percent scored above 80 percent.

In fact, the student heterogeneity in English has been identified as an issue in urban schools, primarily due to the national schools that admit students from rural disadvantaged schools—for instance, via the grade five scholarship exam—who have had limited exposure to quality English education, both at home and at school. This means that a typical classroom consists of students on both extremes of language proficiency, presenting English teachers with the challenging task of catering to different competency levels.

Unequal teacher allocation

Contributing to the problem of unequal student outcomes is an inequitable allocation of English teachers across schools. Contrary to what one would expect, a recent Institute of Policy Studies research reveals that Sri Lanka not only has more than adequate overall English teacher numbers but also an excess of subject-qualified ones—i.e. those with either a university degree in English or who have been specially trained to teach English.

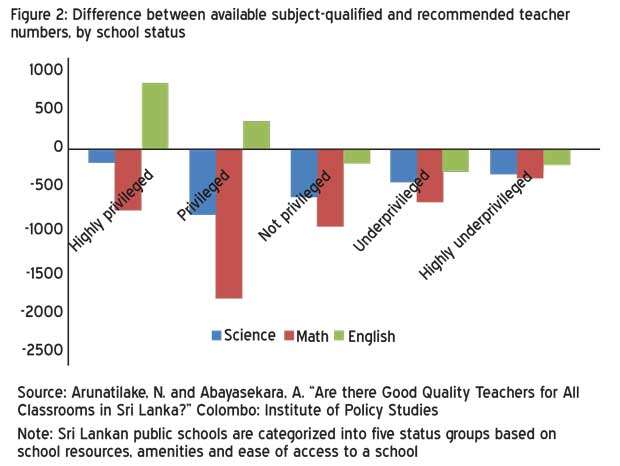

This is in contrast to the sizeable shortages of subject-qualified mathematics and science teachers in the country. The problem appears to be that most of these qualified English teachers are concentrated in more privileged schools, leaving the students in remote schools in the hands of unqualified teachers.

As Figure 2 indicates, while the qualified mathematics and science teachers are lacking in all school types, the qualified English teachers are deficient only in the underprivileged schools; the privileged schools have more than enough competent English teachers. It is thus not surprising that the students from rural primary schools, who enter the urban schools, lack the basic English skills.

Policy implications

The children from rural and less privileged backgrounds are doubly disadvantaged as they lack access to good English education both at home and at school. As a National Education Commission Report puts it, in Sri Lanka, English “continues to be an agent of social differentiation” with good quality education and jobs being limited to a select English-literate population. The fact that many students miss out on being taught by qualified English teachers, despite Sri Lanka having an oversupply of them, is a deep injustice.

A potential measure to deal with the student heterogeneity in classrooms is to cater to the students of different levels of competencies. A study among a sample of grade seven and 10 students in Sri Lanka grouped the students in a given classroom into three levels based on the marks obtained for English at the second term test. The students in these three different levels were taught using different activities, in line with the competencies identified in the Teacher Instructional Manual.

The student performance showed improvements as early as the third term test and were also evident in the end of the year tests, especially among the less able students. Teaching at different levels within a given classroom is however a challenging task and it is important that teacher training programmes include modules on related teaching techniques and preparation of learning material.

To tackle the inequities across the schools, efforts need to be directed at improving teacher allocations to ensure that the disadvantaged schools are staffed with good English teachers. A study on teacher education notes that many existing policies on teacher deployment and transfers in Sri Lanka are limited to paper, with some teachers using political and other influences to get transfers to the schools of their preference.

This is in part possible owing to the current practice of recruiting teachers by the Education Ministry at the central level, which affords flexibility in moving between schools. Giving schools powers to recruit teachers at school level could restrict teacher mobility.

While less privileged schools may not necessarily succeed in attracting qualified teachers, with more restrictions on teacher movement, the recruited teachers in these schools will gain experience overtime, which, along with in-service training, would improve teacher quality.

School-level recruitment has already been implemented in the estate sector schools among the Tamil medium teachers who are in short supply.

(Ashani Abayasekara is a Research Officer at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka. To share your comments with the author, please write to [email protected] more articles, visit our blog http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/)

18 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

18 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

18 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

18 Nov 2024 4 hours ago

18 Nov 2024 8 hours ago