18 Apr 2020 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The growing pressure on Sri Lanka’s scarce foreign exchange resources, due to the wide spread of COVID-19 across the globe, is now more real than ever before. To ease this pressure, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) has taken many measures to attract as well as retain more foreign exchange in Sri Lanka.

The growing pressure on Sri Lanka’s scarce foreign exchange resources, due to the wide spread of COVID-19 across the globe, is now more real than ever before. To ease this pressure, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) has taken many measures to attract as well as retain more foreign exchange in Sri Lanka.

On March 19, 2020, the CBSL curtailed importation of non-essential goods, followed by relaxation of its foreign exchange regulations on April 2, 2020. Here, the CBSL invited Sri Lankans and well-wishers living in the country and abroad to deposit their savings and other funds in foreign currency to the Sri Lankan banking system. This invitation came with the assurance that such deposits will be accepted without any hindrance from the government, CBSL or any other authority.

More recently, the finance minister suspended outward remittances, other than the current transactions through business or personal foreign currency accounts, reduced the first-time migration allowance to a maximum of US $ 30,000 and introduced a Special Deposit Account, which can be opened with inward remittances and would be eligible to a higher interest rate.

Yet, it is uncertain if these efforts alone would be able to address Sri Lanka’s deepening foreign exchange concerns.

This article highlights the importance of remittances to Sri Lanka and outlines how to harness the potential of international remittances to complement the other efforts already taken by the CBSL.

Remittance economy

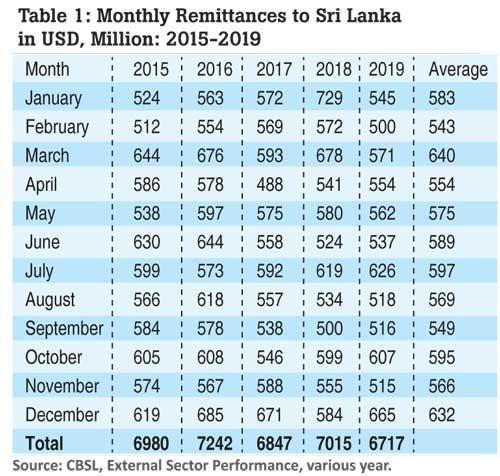

Sri Lanka is often identified as a remittance economy, due its heavy reliance on remittances. In 2019, the Sri Lankan economy received US $ 6.7 billion as remittances, which was capable of covering 84 percent of its trade deficit. Moreover, the recent estimates show that one in every 11 households received international remittances; migrants normally remit once a month and the average amount remitted is Rs.40,000 per month.

Seasonality of remittances

Remittances to Sri Lanka are seasonal and traditionally, peak in the months of April, right before the Sinhala and Tamil New Year and in December, the month of Christmas. During the five-year period from 2015 to 2019, on average, March has brought in US $ 633 million as remittances (Table 1).

Lockdowns

However, by end-March 2020, a majority of the top destination countries of Sri Lankan migrant workers had come under lockdown, in an effort to combat the spread of COVID-19. For instance, around March 9, all schools and universities were closed in Qatar and Saudi Arabia, followed by the subsequent closure of all restaurants, cafes, food outlets and food trucks in popular areas.

By March 20, many labour camps in Qatar – home to migrant workers in the construction sector – were also locked down. Similarly, a large expanse of the industrial areas in Qatar employing migrant workers, was also locked down. While some migrant workers continue to get paid, others in these labour camps and industrial areas were provided no-pay leave, with facilities for food and accommodation.

Adding fire to the flame, the rift between Saudi Arabia and Russia over the supply of oil, in the wake of declining demand for oil in the world market, has resulted in a huge fall in oil prices since March 9. Together with the other issues related to COVID-19 in countries of destination (COD), the impending global recession means less stability and job security for Sri Lankan-origin migrant workers, who under normal circumstances would

remit regularly.

Travel bans

While migrant workers living abroad were locked down, new or returning migrants from Sri Lanka were temporarily banned from entering many countries of destination by mid-March. Initially Qatar imposed a travel ban that restricted Sri Lankan-origin migrant workers entering the country, while Kuwait and Saudi Arabia followed suit by mid-March.

Subsequently, on March 14, the Sri Lanka Foreign Employment Bureau (SLBFE) restricted migrant workers leaving the country for foreign employment. As such, the regular flow of migrant departures were curtailed in mid-March, resulting in a decline in the stock of migrant workers overseas and thereby, triggering the likely decline in remitters.

Migrants and remittances

The decline in the stock of migrants and the economic difficulties faced by those in CODs translate into lower remittances to Sri Lanka. Moreover, for those who were paid, the timing of the lockdowns made it harder to remit their wages via traditional methods, such as visiting a bank or a money transfer operator (MTO). For those who were not paid, remitting to Sri Lanka was not even an option, especially under the growing concerns about their

job security.

Remittance channels

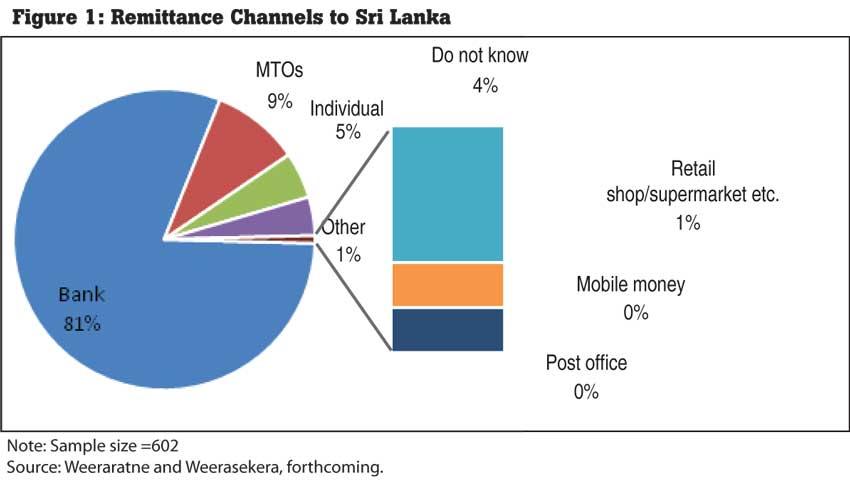

Under normal circumstances, most migrant workers of Sri Lankan origin prefer to remit money via the banking channel, mainly as a result of information provided during pre-departure training in Sri Lanka. For instance, in a sample of 602 migrant households in Sri Lanka, 81 percent indicated that remittance from the countries of destination were sent via banks, while another 9 percent used MTOs.

For most female domestic workers in the Middle East, the nature of work and workplace enable remittances through a bank account of the employer, often via online bank transfers. High-skilled migrants are also most likely to adopt online methods for remittances. Such groups are less likely to be affected by lockdowns and curfews to remit money to Sri Lanka.

Nevertheless, low-skilled workers other than the female domestic workers are more likely to rely on traditional brick and mortar methods for remittances and are likely to be the ones to cut back on their remittances to Sri Lanka in these trying times.

Informal and illegal remittance channels

In addition to formal and legal channels such as banks, MTOs and other authorised money transfer channels, some migrants resort to informal and illegal channels, mainly due to the lower cost of remitting and other reasons, such as absence of a need to prove legal status in COD and door-step delivery in Sri Lanka.

Recent estimates indicate that the average cost of remitting to Sri Lanka via the banking channels is 5.4 percent of the amount remitted, while via the MTO channels the cost is 3.7 percent. There are no reliable estimates about the share of remittances sent via informal and illegal channels or its cost.

The informal and illegal channels of remittances operate by the remittance service provider collecting remittances in the COD (in foreign currency) and distributing the same in Sri Lanka using his/her LKR funds in Sri Lanka, often through a partner here. Such operations restrict the much-needed foreign exchange from reaching Sri Lanka. Instead, foreign exchange destined to Sri Lanka remains in the COD. This is a serious concern in the current context, with the decline of foreign exchange to Sri Lanka.

Future scenario

The travel restrictions on many countries are likely to remain effective in the next couple of months, eliminating the possibility of departures for the already processed and approved job orders from Sri Lanka. On the other hand, the approaching global recession will decrease the demand for foreign workers. At the same time, migrant workers currently in CODs will undergo severe economic stress or will be compelled to return to Sri Lanka if rendered unemployed.

Similarly, the migrant workers, who were able to return to Sri Lanka, especially from Italy, before the closure of borders in mid-March, are very likely to be laid off and not have a job to return to in the future. As such, even after the travel restrictions are lifted, the availability of employment opportunities for migrant workers from Sri Lanka would be slim. Together, all these factors will contribute to a decline in the stock of Sri Lankan-origin migrant workers and thereby a drop in remittances to Sri Lanka in 2020.

Way forward

In this context, to address the growing foreign exchange concerns, Sri Lanka needs to adopt aggressive measures to increase the amount of foreign exchange received as international remittances in 2020. In addition to the already proposed measures by the CBSL, the following are some strategies to maximise the receipt of remittances to Sri Lanka in 2020:

1. Encourage migrant workers currently under lockdown in CODs to adopt online methods to remit money to Sri Lanka. To this end, the SLBFE and Foreign Employment Ministry can adopt a targeted social media campaign to reach Sri Lankan migrant workers abroad.

2. Encourage Sri Lankan banks operating in CODs to adopt door-step collection methods to encourage remittances by Sri Lankans in lockdown. The CBSL and Foreign Affairs Ministry can spearhead this effort by guiding the Sri Lankan missions in CODs to liaise with relevant financial authorities in CODs to enable such a manoeuvre.

3. Offer benefits for those collecting remittances from formal channels in Sri Lanka, thereby mobilising remittance receivers in Sri Lanka to influence remitters overseas. A few strategies to implement this would be to:

1. Provide door-stop delivery of remittances in Sri Lanka by commercial banks and MTOs during curfew hours. The CBSL could guide commercial banks and MTOs to offer such facilities.

2. Commercial banks to take initiatives to provide the much-needed in-kind assistance, for those collecting remittances via formal channels.

4. Encourage those using informal channels to use formal channels. Towards this effort, a global dialogue needs to be initiated to:

1. Negotiate with MTOs and exchange houses operating in CODs to reduce their fees for remittances, to lower the cost of remittances in formal channels.

2. Relax documentary requirements in formal channels to attract more remitters into formal channels.

(Bilesha Weeraratne is a Research Fellow at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). To talk to the author, email [email protected]. To view this article online and to share your comments, visit the IPS blog ‘Talking Economics’ - http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/)

25 Dec 2024 9 hours ago

25 Dec 2024 9 hours ago

25 Dec 2024 25 Dec 2024