23 May 2022 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Whether RW can motivate a public service, which is actively participating in anti-government rallies and protests, remains to be seen

Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa (MR) resigned on May 09, 2022, soon after sending mobs to attack the peaceful protesters at Galle Face (dubbed Gotagogama). On May 12, 2022, Ranil Wickremesinghe (RW) took oaths as the new Prime Minister (PM). The appointment of RW to this prominent post by President Gotabhaya Rajapaksa (GR) has been condemned by those who argue that the former’s track record as a politician (1978 to the present) is far from spectacular.

Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa (MR) resigned on May 09, 2022, soon after sending mobs to attack the peaceful protesters at Galle Face (dubbed Gotagogama). On May 12, 2022, Ranil Wickremesinghe (RW) took oaths as the new Prime Minister (PM). The appointment of RW to this prominent post by President Gotabhaya Rajapaksa (GR) has been condemned by those who argue that the former’s track record as a politician (1978 to the present) is far from spectacular.

After all, under his leadership, the United National Party (UNP) became so unpopular that it failed to win a single seat in the 2020 General Election (GE), whereas the Samagi Jana Balavegaya, founded by former UNP stalwart Sajith Premadasa in February 2020, secured 54 seats, thereby becoming the largest opposition party in Parliament.

However, the UNP was able to secure a solitary national seat in Parliament via the proportional representation system – a vacancy filled after a lapse of nearly one year by RW himself (a lawyer by training), who having lost his electoral seat, was chomping at the bit in his ancestral home in Colpetty, which we are told, will be bequeathed to his alma mater, Royal College.

Vicious circle

Thus, the man who slipped in to the “chamber” through the back door now finds himself PM of Sri Lanka for the sixth time in his career. Though the hardcore ‘Pohottuwa’ MPs may consider it a smart move by the president to make a man rejected by the voters at the last GE, the new PM, the mass protesters at Galle Face have reacted with outrage, which is bad news for the economy.

To solve the economic crisis, political stability is a sine qua non. What the country needs now is more political stability, not less. If the political crisis deepens, due to the appointment of a man whom the protesters view as a “no-hoper” to the coveted post of PM, so will the economic crisis, which means the ongoing shortage of essential goods and services will become even more severe, prices will rise even higher and the proportion of the population on the brink of starvation will become even larger.

Conversely, if the economic crisis worsens, so will the political crisis and any hopes of a surge in tourism and foreign direct investment (FDI) in the near future will evaporate. Hence, the probability of the president’s choice of PM creating a vicious circle that could drive the country to the brink of anarchy is exceedingly high.

Soon after becoming PM, RW said things would get worse before they get better. Indeed, things will soon get worse with the government finding itself incarcerated in the dungeon of bankruptcy. But how and when will things get better? The current economic situation is so grim that only the Gods can answer this question.

Begging bowl

In contrast to those who view RW as a failed politician, the hardcore UNP supporters believe that in the context of the current political and economic crises, which are interwoven into a double helix, he’s the best man to pull the government out of the dungeon, given his vast experience with governance, his sophisticated intellect, his liberal economic orientation, his democratic political ideology and his cordial relations with the bilateral and multilateral donor community.

RW has certainly hit the ground running. The day after taking oaths, he initiated talks with the foreign envoys on the formation of a foreign consortium for financial assistance and declared that his sole purpose as PM was to ensure the recovery of the Sri Lankan economy.

His immediate task, therefore, is to pass the celebrated begging bowl around and hope the donor community as a whole will give generously, so that there will be sufficient bridge-financing to keep the economy afloat until such time that an IMF bailout is secured. In the absence of bridge loans, the economy is almost certain to collapse, which means no power, no fuel, no food, no medicines and no essential services. The country will simply fall apart.

We are told an IMF deal could take anywhere from three to six months to negotiate as the IMF needs sufficient time to determine whether satisfactory progress is being made by the government in respect of external debt restructuring. The IMF will also be reluctant to lend to a country that is politically unstable. This is a crucial litmus test for the new PM.

Securing an IMF bailout will indeed be a feather in his cap. But if the IMF says no to the bailout, the blame will fall squarely on his shoulders as GR is leaning heavily on him to play a key role in facilitating a rapid and sustainable economic recovery. The president is acutely aware that if the economic crisis deepens and precipitates anti-government riots, he could well be forced out of office and that an IMF-supported macroeconomic stabilisation programme is the only way out of the mess created largely by his regime.

According to the experts, had he gone to the IMF two years ago, the foreign currency crisis now plaguing the country could have been mitigated, if not averted, through prudent monetary and fiscal management combined with concerted efforts to negotiate a feasible debt restructuring arrangement with the creditors. So, why did the president wait until the economy went into a tailspin to bite the bullet? Only he can answer that question.

The government made a public announcement on April 12 that since it was running out of foreign currency reserves, it would be suspending its debt service obligations and hastened to add that this was a soft, not a hard default. In other words, its intention was not to write off the entire external debt of US $ 51 billion (of which the private sector’s share is negligible) but rather to reschedule the loan repayments in consultation with its creditors.

No doubt it was the unilateral nature of this announcement that prompted Fitch Ratings to promptly downgrade Sri Lanka from ‘CC’ to ‘C’. This means that foreign commercial banks may not provide any more loans to Sri Lanka and that the letters of credit provided by the local banks may not be accepted by foreign suppliers.

IMF bailout

Debt restructuring could be a slow and cumbersome procedure, especially in respect of international sovereign bonds (ISBs), as there is every prospect of commercial creditors resorting to high-powered litigation to recover their loans, in which case the process could drag on for years. It is therefore imperative for the government to embark on debt restructuring in a manner that is in accordance with the IMF’s expectations.

In any event, a bailout in the form of an Extended Fund Facility (EFF), regardless of its size, is unlikely to solve the foreign exchange crisis, given that the monthly import bill is in the region of US $ 2 billion. To solve the crisis, the country needs a rapid expansion of exports and FDI inflows plus the IMF bailout, not to mention a healthy revival of tourism.

The IMF funds are not released in one go but in tranches over a three to four-year period, where each tranche is tied to a tough set of policy and regulatory reforms. What is important to note is that an IMF-supported macroeconomic stabilisation programme would instil the kind of monetary and fiscal discipline in the public service that would empower it to extricate the economy from the swamp of debt distress and place it on an equitable growth path designed to achieve the twin goals of poverty reduction and debt sustainability in the medium term.

An upgrading by Fitch Ratings will be significant, as it would lead to enhanced credibility of the Sri Lankan government in the eyes of the international donor community as well as private investors. But this upgrading is unlikely to take place until the country can demonstrate that it has made significant progress towards attaining debt sustainability via debt restructuring as well as fiscal consolidation. The country has a long way to go in this regard and with governance in complete disarray (a third crisis, perhaps), it will be impossible for RW to get his act together until a competent and capable Cabinet has been put in place by the president. If the same old faces appear (the bad, the wicked and the ugly), it will be curtains for RW.

Meanwhile, Fitch Ratings has further downgraded Sri Lanka from ‘C’ to ‘RD’ (restricted default), as the country fell into default for the first time on May 18.

We should note that the previous attempt by the IMF to stabilise the Sri Lankan economy and accelerate growth via an EFF (2015-2019) met with limited success, largely because the coalition government formed by the UNP and Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) was shaky from the very beginning. Since the president (Maithripala Sirisena/SLFP) was inward-looking and the PM (RW/UNP) outward looking, the two of them failed to find common ground in respect of policy change and institutional reform, much to the dismay and disappointment of local and foreign investors.

Moreover, due to the constant tug-of-war between the president and PM, which created serious tensions within the coalition, the government did not pursue fiscal consolidation targets linked to the EFF with much enthusiasm; it also did not create a dynamic business environment designed to enhance FDI inflows and promote a rapid growth of exports. To make matters worse, the country was rocked by the 2019 Easter bombings, which dealt a severe blow to tourism.

External debt trap

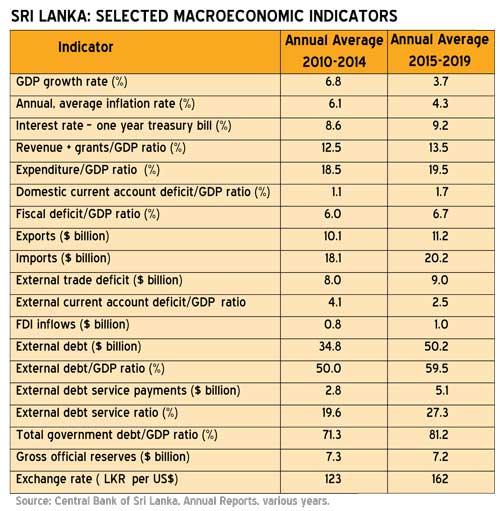

The table shows how the economy fared during the five-year period 2015-2019 (Maithripala Sirisena government) compared to the previous five-year period (Mahinda Rajapaksa government). Though the results are mixed, it is clear that in respect of some key macroeconomic indicators, such as GDP growth, domestic current account balance/GDP ratio, fiscal deficit/GDP ratio, external trade balance, external debt/GDP ratio and total government debt/GDP ratio, the Rajapaksa government performed far better than the Sirisena government.

The most disappointing aspect of the Sirisena government’s performance was the average GDP growth rate of 3.7 percent per annum as against an annual average of 6.8 percent achieved by the Rajapaksa government. In terms of overall economic performance, the Rajapaksa government appears to have outshone the Sirisena government, which is ironic since it was the latter that received an IMF bailout of US $ 1.5 billion, not the former.

It is critical for the current regime to note that for an IMF-sponsored macroeconomic stabilisation programme to work, the government must be fully committed to achieving the stipulated goals and targets. This is where leadership comes in. Whether RW can motivate a public service, which is actively participating in anti-government rallies and protests, remains to be seen.

We may also note the following: the MR regime, which ruled from 2006 to 2014, relied heavily on foreign commercial loans to finance its expansionary fiscal policy and so did the Sirisena regime. The licence for the Central Bank to secure these loans was given in the first instance by MR and in the second instance by RW, who was responsible for overseeing monetary and fiscal policy under the Sirisena regime.

From 2010 to 2014, the external debt-to-GDP ratio averaged 50 percent per annum, while from 2015 to 2019, it averaged almost 60 percent per annum. Clearly, no attempt was made by the Sirisena regime to reign in the external debt. Thus, both regimes are responsible for creating the external debt trap, in which the country is now ensnared. They also contributed significantly to the massive crisis in budgetary operations the government is now facing, as explained below.

Fiscal deficit

The average, annual fiscal deficit was high under the Rajapaksa regime (6.0 percent) and even higher under the Sirisena regime (6.7 percent). The larger the gap between revenue and expenditure, the larger the fiscal deficit. This is 101 Economics.

Over the years, the revenue/GDP ratio has undergone a steady decline while the expenditure/GDP ratio has moved in the opposite direction. This has led to a gradual widening of the fiscal deficit which, in turn, has necessitated a higher level of borrowing to finance the deficit. Fiscal consolidation entails a gradual narrowing of the fiscal deficit to a manageable level through improved revenue performance combined with a rationalisation of recurrent and capital expenditures.

Though both regimes presented bold fiscal consolidation targets in their annual budgets, neither made a serious effort to achieve them. Hence, the annual fiscal deficits remained high. Both regimes were also guilty of handing out tax holidays and fiscal relief to one sector and/or favoured project after another, a characteristic feature of crony capitalism. In 2020, the fiscal deficit jumped to 11.1 percent, due to the chaos created by the global pandemic and increased further to 12.2 percent in 2021.

Due to low-income tax takes, Sri Lanka has one of the lowest revenue/GDP ratios in Asia. This was always a fiscal path that was inevitably headed for a crash-and-burn and the COVID-shock simply brought forward what was inevitable after decades of fiscal recklessness. If Sri Lanka had strived to attain and maintain a revenue/GDP ratio of 15-17 percent, none of the chaos that we now see would have materialised. In 2021, revenue + grants amounted to only 8.7 percent of GDP. To double this ratio in the shortest possible time is a major challenge for the government. This would entail a substantial increase in direct as well as indirect taxes.

Revenue collection is declining so rapidly that the government has no option but to keep printing money to finance recurrent expenditures. Only a handful of countries in the world are currently experiencing hyperinflation and Sri Lanka is one of them, with the inflation rate hovering in the region of 30 percent. Several factors are contributing to hyperinflation in Sri Lanka, including money printing, a steep depreciation of the local currency, a critical shortage of consumer and intermediate goods and a steep increase in international petroleum prices.

Double helix

Shortly after the Sirisena government (UNP/SLFP coalition) came into power, it enacted the 19th Amendment to the Constitution designed to strengthen the powers of the PM and correspondingly weaken the powers of the president. Despite enjoying the benefits of the 19th Amendment for a full five years, RW failed to provide the necessary guidance and leadership for moving the economy to a higher growth trajectory. On the contrary, the country underwent severe economic stagnation while irresponsible spending and borrowing led to a substantial increase in the external debt burden. If the UNP got wiped out in the 2020 GE, it is because the people were totally fed up with RW and viewed him as a weak leader and a failed politician.

After securing a handsome victory in the 2020 GE, the Sri Lanka People’s Freedom Alliance, led by GR, enacted the 20th Amendment to the Constitution, designed to weaken the powers of the PM and make the president all-powerful. There are several reasons why RW’s job is far more challenging under the present regime than under the previous one.

First, as PM, he enjoys less power now than he did under the previous regime on account of the 20th Amendment and the Cabinet soon to be appointed by the president will not have a single UNP member in it, which is something he will have to contend with; second, the country is facing the worst economic crisis in its modern history, compounded by a war in Eastern Europe, which is threatening to precipitate a global recession; third, Parliament has become dysfunctional, due to severe internal conflicts and dissensions; fourth, the people have become so disenchanted with the president that they want him out and fifth, the economic and political crises have dovetailed into a single overarching crisis, a double helix, that is propelling the country towards anarchy.

Protest marches, demonstrations and strikes are now a frequent occurrence in various parts of the country. The international donor community as well as Fitch Ratings must be watching all of this with great interest as right now the country is being rocked by political instability.

We need a competent finance minister

As mentioned above, it may take a while for an IMF deal to be secured. In the meantime, the country needs to rebuild its official reserves, which will require a combination of fiscal consolidation, tight monetary policy, a market-determined exchange rate, extra efforts to boost tea and other cash crop exports and aggressive tourism promotion.

Remittances are a wild card but the government can make it easier for overseas Sri Lankans to hold guaranteed dollar or euro deposits in domestic banks. While key adjustments have been undertaken by the government during the past two months in respect of monetary policy, little or no progress has been made with fiscal consolidation to date, which is why the economic crisis is continuing to worsen. The need for a competent finance minister to be appointed soon is critical. If only we had someone like the Indian finance minister in our Parliament!

Can a failed politician who has become PM for the sixth time defy all odds and solve this crisis, which is threatening to create massive hunger, deprivation and social unrest? If he fails again, his critics will say, “We told you so.” If, on the other hand, he rises to the occasion, stays away from crony capitalism and takes the country on the path to economic recovery before the social unrest transmutes into a political tsunami, it will be nothing short of a miracle.

When the going gets tough, the tough get going. It is up to the PM to prove that he is no weakling. Rumour has it that his hero is Winston Churchill. If he can take a leaf out of Churchill’s book, more power to his elbow.

(Seneka Abeyratne is a retired economist/international consultant to ADB/Manila. He can be contacted at [email protected])

23 Dec 2024 4 minute ago

23 Dec 2024 49 minute ago

23 Dec 2024 2 hours ago

23 Dec 2024 2 hours ago

23 Dec 2024 2 hours ago