02 Dec 2020 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The Central Bank, at its recent monthly monetary review meeting, decided to continue its accommodative monetary policy stance to boost economic growth while recognising the absence of demand-driven inflationary pressures. Accordingly, the Central Bank will maintain its Standing Deposit Facility Rate (SDFR) and Standing Lending Facility Rate (SLFR) at their current levels of 4.50 percent and 5.50 percent, respectively.

The Central Bank, at its recent monthly monetary review meeting, decided to continue its accommodative monetary policy stance to boost economic growth while recognising the absence of demand-driven inflationary pressures. Accordingly, the Central Bank will maintain its Standing Deposit Facility Rate (SDFR) and Standing Lending Facility Rate (SLFR) at their current levels of 4.50 percent and 5.50 percent, respectively.

The Central Bank also intends to introduce maximum interest rates on mortgage-backed housing loans for salaried workers and lending targets for selected sectors of the economy in the near future.

Central Bank alone cannot do the trick

While the Central Bank readily adopted monetary easing measures, adhering to the unusual directives given by the President in public a few months ago, the effectiveness of such measures in boosting economic growth is doubtful, as explained in my last week’s column in Daily Mirror.

To be fair, the Central Bank alone is not responsible for the impending growth slowdown, since various non-monetary factors such as human resource skills, knowledge inputs, technology infusion, competitiveness, efficiency, research and development (R&D), politics and institutions have a greater bearing on GDP growth. Given Sri Lanka’s poor track record with regard to these growth drivers, the Central Bank does not have much space to play around with its monetary policy tools to foster economic growth.

Outdated credit controls lead to financial repression

It is disturbing to note the Central Bank’s intention, as declared in its latest monetary policy review, to reintroduce some obsolete direct credit controls for the sake of economic recovery amidst the COVID-19 crisis. Such controls were well-tested and found to be failed prior to economic liberalisation in 1977.

Hence, the Central Bank abandoned those controls since then and moved towards market-oriented monetary tools culminating to launch the flexible inflation-targeting (FIT) monetary policy framework about two years ago.

Reintroduction of direct credit controls is tantamount to a reversal of the market-oriented policy reforms adopted hitherto and such measures will pave the way to financial repression, which means that administrative credit controls prevent efficient functioning of financial institutions.

The adverse effects of financial repression experienced by developing countries across the world some decades ago are well documented in economic literature, notably by Ronald McKinnon and Edward Shaw in their famous writings of the early 1970s.

Empirically, a major shortcoming of directed credit allocations targeting selected economic sectors, as envisaged in the monetary policy review, is that those sectors are chosen by the authorities at their discretion, mostly driven by political considerations rather than by economic realities.

Hence, such arbitrary directives tend to create market distortions and resource misallocations, resulting in deterioration of efficiency and productivity, pushing the economy further downward.

Zero real interest rates for savers

The government takes the advantage of the low interest rate environment, as it can borrow at lower cost in the domestic market to finance its expanding budget deficit. This is an outcome of financial repression, which forces to push down borrowing costs below market rates, giving low returns to savers.

The yield on 364-day Treasury Bills is down to around 5 percent at present, compared with 8 percent a year ago. This means that the real interest rate (nominal interest rate minus inflation) received by a 364-day Treasury Bill holder is zero now, given the present inflation rate of 5 percent per annum.

Interest rate caps on housing loans benefit privileged employees

The interest rate ceilings to be imposed by the Central Bank for mortgage-backed housing loans too appear to be unjustifiable, as it is not clear how such concessions would contribute to tackle the current economic crisis, apart from helping to resolve housing problems of a privileged group of employees, who are already enjoying regular incomes in the organised sector.

By contrast, thousands of workers in the unorganised sector are reported to have no means for survival, due to the loss of their jobs and income-generating activities in the pandemic and no coherent policy strategy seems to be forthcoming to tackle their grave problems.

Ironically, it is reported that several unauthorised occupants of Mahaweli lands in the Mayurapura area in Hambantota were forcefully evicted by the authorities a few days ago ignoring the pandemic risks.

“In the face of this pandemic, being evicted from your home is a potential death sentence,” according to the UN’s COVID-19 guidance note on prohibition of evictions.

Monetary easing measures

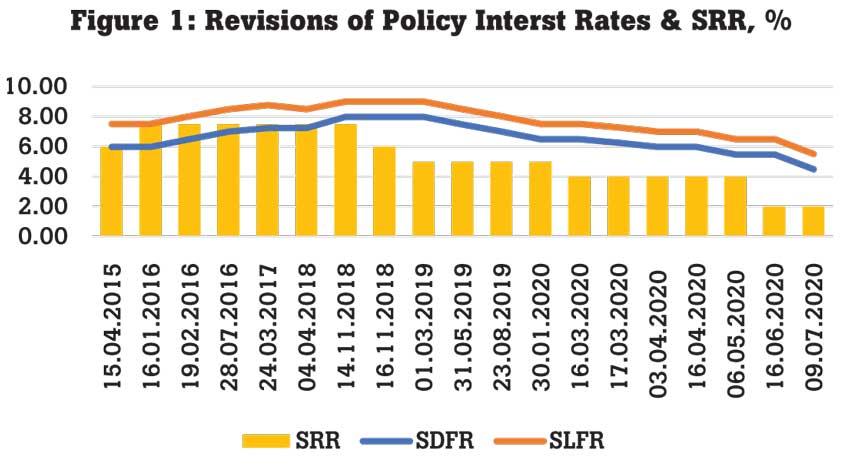

The relief measures provided by the Central Bank to the affected households and businesses since the outbreak of the pandemic have been quite extensive. It has implemented a series of monetary easing measures, including sequential reductions of the policy interest rates and Statutory Reserve Ratio - SRR (Figure 1).

Such measures helped to inject substantial liquidity into the market and to reduce borrowing costs significantly. Concessional credit schemes were also introduced to facilitate the activities of small and medium-scale enterprises (SMEs), alongside debt moratoria granted for businesses and individuals distressed by the pandemic.

Private sector’s response insignificant

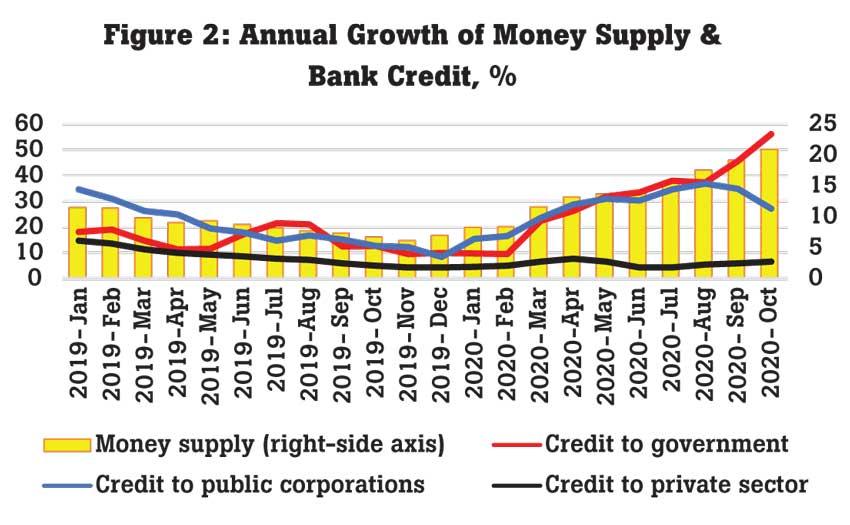

In spite of the Central Bank’s monetary easing, the year-on-year growth of bank credit to the private sector remained stagnant below 5 percent, whereas credit to the government rose by as much as 56 percent and credit to public corporations by 27 percent by end-October 2020 (Figure 2).

The Central Bank has accommodated government finance requirements by directly purchasing Treasury Bills at primary auctions. The exorbitant growth of credit to the government sector led to accelerate the year-on-year money supply growth to 21 percent by October.

Negative GDP growth

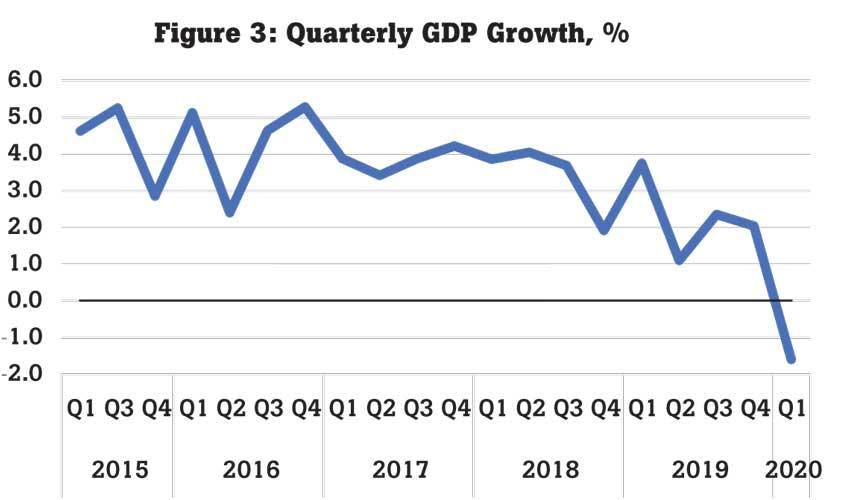

The Sri Lankan economy experienced negative GDP growth rate of 1.6 percent (year-on-year basis) in the first quarter of 2020 largely reflecting the combined effects of local economic disruptions caused by the lockdowns, curfews and travel bans compounded by the subdued global demand in the face of the pandemic.

In the first quarter of 2020, the agriculture sector and industrial sector contracted by 5.6 percent and 7.8 percent, respectively while the services sector reflected a moderate growth of 3.1 percent. The unemployment rate rose to 5.6 percent in the first quarter of 2020, compared with 4.8 percent in the corresponding period of 2019, as a consequence of the islandwide lockdown imposed from mid-March to mid-May 2020.

The anticipated economic recovery during the rest of this year and next few years seems to be unlikely in view of the continuation of the pandemic. According to the official forecasts, GDP growth rate in 2020 would decline to around -2.0 percent, compared with 2.3 percent growth in 2019.

However, the IMF forecasts that the economy would contract by 4.6 percent this year, which is significantly higher than the contraction of 0.5 percent predicted in April.

Growth constraints beyond pandemic

The economy was on a downward path even prior to the outbreak of the pandemic (Figure 3). The average quarterly GDP growth rate was only 3.8 percent during 2015-2019. Hence, the present growth slowdown cannot be totally attributed to the pandemic.

GDP growth averaged only around 5 percent a year during the last four decades, although the successive governments promised to achieve growth rates of 7 percent or more in their periodic economic agendas.

Limited growth potential to remain

The low growth trajectory in the past reflects Sri Lanka’s failure to develop the necessary pre-conditions to boost growth in line with the evolving growth paradigms. Knowledge, innovation, technology and entrepreneurship have become the key drivers of economic growth in the modern world, in addition to the inputs of labour, land and capital, which were prominent in the conventional growth models.

The countries that have been able to progress towards the status of ‘knowledge economy’ accelerated GDP growth fast, as evident from the success stories of East Asian countries. A knowledge economy is one that creates, disseminates and uses knowledge to enhance its growth and development. Such an economy is characterised by high value-added products containing advanced knowledge inputs.

Sri Lanka has a long way to achieve the knowledge economy status and as a result, her growth potential will continue to remain low in years to come, irrespective of the monetary easing policy stance. Direct credit controls of the Central Bank will only foster financial repression further aggravating the economic setback.

(Prof. Sirimevan Colombage is Emeritus Professor in Economics at the Open University of Sri Lanka)

24 Dec 2024 8 minute ago

24 Dec 2024 1 hours ago

24 Dec 2024 2 hours ago

24 Dec 2024 3 hours ago

24 Dec 2024 4 hours ago