05 Jul 2022 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The decision by the Cabinet to partially lift the Family Background Report (FBR) requirement for female migrants is long overdue and a welcome move to promote female labour migration from Sri Lanka. The discriminatory FBR policy was introduced in June 2013 in order to restrict females with children under the age of five and to discourage females with older children from taking up foreign employment.

The decision by the Cabinet to partially lift the Family Background Report (FBR) requirement for female migrants is long overdue and a welcome move to promote female labour migration from Sri Lanka. The discriminatory FBR policy was introduced in June 2013 in order to restrict females with children under the age of five and to discourage females with older children from taking up foreign employment.

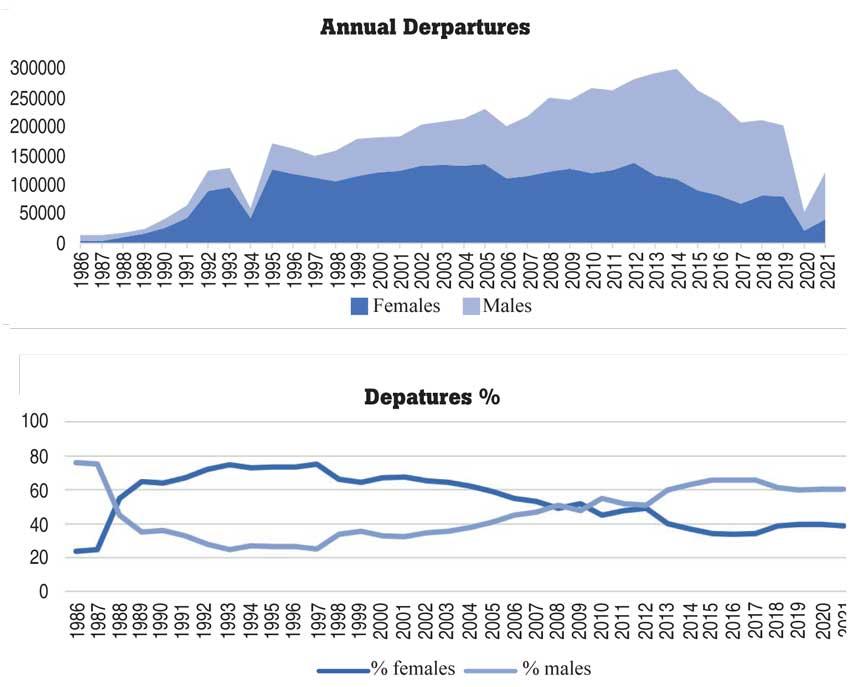

The FBR initially covered only female domestic worker departures, but in August 2015, this was expanded to cover all females. As a result, from 2013 onwards the dominance of women among worker departures declined significantly.

FBR’s intended objectives

The FBR requirement was introduced based on the notion that a mother’s absence has negative social implications for the children left behind. Generally, this is an acceptable argument. However, it is important to consider the economic context and income constraints faced by the mother, the related stress and other facets that contribute to the wellbeing of a child.

The critical weakness around the introduction of this policy was the absence of sound empirical evidence of the negative social impacts brought about by the absence of the migrant mother, which the policy aimed to address.

Similarly, the continuation of the policy lacked empirical evidence to prove any improvement to the wellbeing of children of mothers held back by the policy. Hence, although the FBR purportedly “protected against family breakdown,” it is unclear whether staying together as a family contributed to the greater well-being of the children”.

Outcomes of FBR policy

Apart from the absence of evidence confirming any positive outcome of the policy, there was ample evidence of the unintended negative consequences. Research conducted by the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS) in 2016 showed that although the FBR was successful in restricting females migrating for domestic work, the policy promoted migration outside Sri Lanka’s legal framework or through visitor visas and thus increasing their vulnerability at destination.

Additionally, vulnerability was heightened due to women resorting to corrupt practices to circumvent the FBR requirement by forging documents. In 2015, the price of a forged FBR ranged from Rs. 25,000-85,000. Often, these amounts were paid by the sub-agent or the licensed recruitment agent, leading to abuse and exploitation of the potential migrant women during recruitment. Similarly, FBR is also associated with delays in the recruitment process.

More recent evidence from IPS research shows that the FBR policy resulted in decreased departures among lower-skilled groups and increased departures among middle-level and professional workers. This increase in higher-skilled workers is linked to FBR-related corruption and misreporting of skills to avoid the policy.

Thus, the policy is associated with greater involvement of lower-skilled workers in recruitment-related corruption, higher exposure to recruitment-related vulnerability, and lower foreign employment opportunities. One of the most critical gaps in this policy as highlighted in previous IPS research was the absence of a mechanism to support those who were “not recommended” for migration under the FBR and were forced to remain in Sri Lanka with their children.

Reluctance to reverse

Until its removal in June 2022, the FBR policy had been revisited several times. For example, in 2016, as a result of research evidence and lobbying by different stakeholders, a Parliamentary Sub-committee was established to review the policy.

As noted by the author in another study for the Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD), the then ministry-in-charge and the Sri Lanka Bureau of Foreign Employment (SLBFE) encouraged repealing the FBR based on both evidence and stakeholder perceptions.

Yet, the Sub-committee favoured continuation of the policy. Despite mounting evidence and support from the relevant stakeholders, the FBR mandate remained for nine years mainly due to the absence of political will to accept evidence-based research and advice by qualified/relevant stakeholders. The underlying reason for this was the possible political backlash for removing a populist policy – though not backed by an iota of evidence.

Increasing formal remittances

Migration and remittances can contribute significantly to bridge Sri Lanka’s foreign exchange shortage. Research reveals that compared to men, women are more reliable remitters, although their wages are relatively lower. As such, it is important to facilitate foreign employment opportunities for women.

The removal of the FBR requirement is likely to increase female departures by enabling women to make a labour market decision independent of their maternal status, while minimising delays and vulnerability in the recruitment process.

However, to reap the desired outcome of more remittances from higher departures, the new stock of females departing for foreign employment in the absence of the FBR must be convinced to remit through formal channels. Here, it is important to identify the key demographics of this segment of migrants who now face more relaxed regulations for migration (likely to be married women with mostly young children and leaving children in the care of a female extended family member) and design incentives accordingly.

In addition to the traditional incentive schemes proposed in recent weeks to promote formal remittances, a few recommendations targeting female migrants are as follows:

■Provide unmatched incentives for remittances sent through children’s bank accounts.

a. For every X amount (i.e. US$ 100) remitted per month through a child’s bank account

(I.) Y amount (i.e. US$ 5) will be contributed by the state towards an education fund account for that child maintained in the same bank, which can be withdrawn annually for year-end educational expenses.

(II.)Tie a children’s medical insurance, where medical reimbursement to the value of Y amount (i.e. Rs. 2000) per month can be received.

(III.) Receive a child nutrition pack

b. Once remittances sent through the child’s bank account exceed X amount (i.e. US$ 1000),

(I.) The child will receive a free life insurance cover.

(II.) Become eligible for an internship at the bank upon reaching the age of 18.

■Tie incentives for remittances through support towards the children’s caregiver.

a. For every X amount (i.e. US$ 100) remitted per month through a bank account

(I.) Receive a caregiver nutrition pack worth Y amount.

(II.) Receive a caregiver medical care insurance coverage.

(The writer is a Research Fellow and Head of Migration and Urbanisation Research at IPS. Prior to re-joining IPS in 2014, she was a Postdoctoral Research Associate at Princeton University, New Jersey, USA. Her research interests include internal and international migration, urbanisation, economics of education, labour economics, economic development, econometrics & economic modeling, and economics of sports. She holds an MA in Economics from Rutgers University, USA and an MPhil and PhD in Economics from the City University of New York, USA.)

23 Dec 2024 17 minute ago

23 Dec 2024 1 hours ago

23 Dec 2024 2 hours ago

23 Dec 2024 2 hours ago

23 Dec 2024 2 hours ago