31 Dec 2019 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

From ancient times, humans have used the force of water flowing in streams and rivers to produce motivepower. However, such use is not very evident in the history of Sri Lanka.

From ancient times, humans have used the force of water flowing in streams and rivers to produce motivepower. However, such use is not very evident in the history of Sri Lanka.

Hydropower is one of the first sources of energy used for large-scale electricity generation, and still is the largest single renewable energy source for electricity generation in Sri Lanka.

In 2017, hydropower accounted for about 45 percent of total electricity generation in Sri Lanka and 90 percent of total Grid-connected electricity generation from all renewable energy sources. The annual share of total electricity generation by hydro power, whether it is large-scale or small, varies considerably depending on hydrological cycles.

Water: From where?

Understanding the water cycle is important to understand hydropower. The water cycle has three steps:

In Sri Lanka, being located in the intertropical zone of the globe, we have two distinct monsoon seasons and as a result, two distinct dry and wet seasons.

The precipitation to the catchment areas of the rivers and the stream flows in them are having starkly different behaviors during these seasons.

In a normal year, South-West monsoons are expected in the months of May to August, and the North-East monsoons are in October to December. The Dry Season as a result of this, is between January to April and the Wet Season comes from about October to December. There are also brief inter-Monsoon rains prior to setting-in of the Monsoons proper.

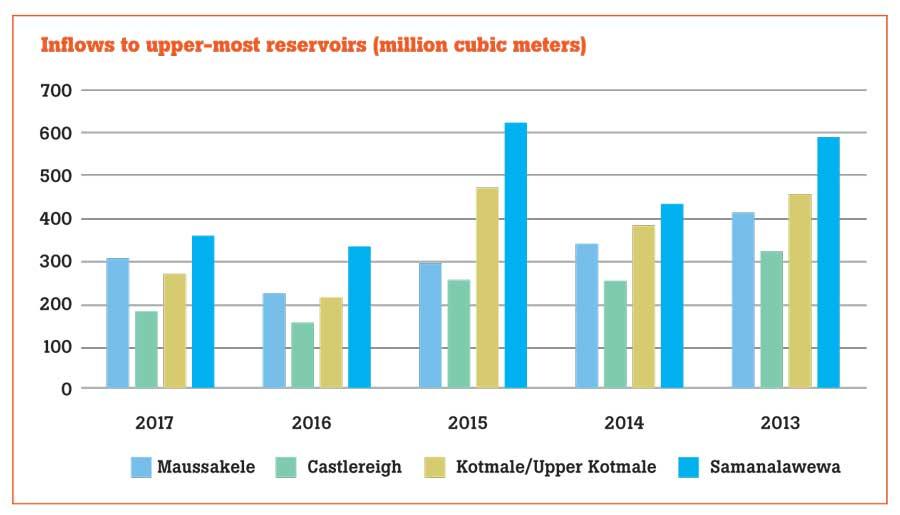

However, variations in these patterns had been observed over the last few decades. The graph below shows the wide variations of the inflows during the last five years. The situation is also affected by other global climatic conditions, such as el Niño or la Nina.

For major hydropower developments, if the other conditions are conducive, it may be economical to have the stream flow of the monsoon seasons regulated, so that the water more abundantly available in the wet seasons is stored and to be used during the drier periods when the stream flows are minimal (storage schemes).

When such storage is found uneconomical, stream flow may be used as it flows in what is generally known as run-of-the riverschemes. Larger amount of water inflows generally come from the North-East monsoon, mainly due to meteorological conditions of the Bay of Bengal during those months.

Hydroelectric power basics

The energy that is harvested from precipitation could be of two forms. Firstly, it may be potential energy (in this case, due to its storage at a higher elevation) or else, kinetic energy (by virtue of its flow).

In either case, therate of the water flow and the change in elevation (a fall) from a higher point to a lower point determine the amount of energy available in that moving water.

For example, the water descending rapidly from a high point, such as upper reaches of Maskeliya Oya, to a lower point of Maskeliya Oya in Laxapana the potential energy of it could be converted in to electricity. When such water is channeled through an appropriate turbine, that energy is transformed into motive power, which would in turn drive an electricity generator.

Similarly, at Bowatenne or Udawalawe, where the volume rate of flow is more predominant than the differences of elevation, the kinetic energy of the flow of water is transformed into motive power, which would in turn drive an electricity generator.

History of hydropower development in Sri Lanka

The first use hydro power in contemporary Sri Lanka may have been for processing of tea in the hill country during early British rule.Some tea factories then had used water wheels for motive power. The first hydro turbines of tea factories have been in operation in the latenineteenth century. It was estimated that around 500 such micro-hydro plants had been in operation from that time, both for motive power and electricity.

It is in record that a small hydroelectric power plant at Blackpool had started operation for Nuwara Eliya Electricity Scheme in 1912. By year 2002, forty nine (49) of such old power plants were still in operation in estates, with a total installed capacity of 3,340 kW.

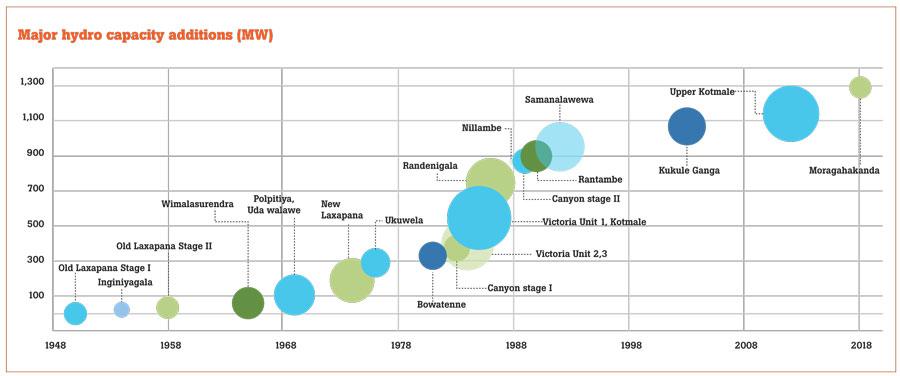

As we all know, the first major(25 MW) hydroelectric power plant, coupled with a 66 kV high voltage transmission line to Kolonnawa, was commissioned in 1950 due to the laudable pioneering efforts of Late D. J. Wimalasurendra.

Major hydroelectric capacity additions were gradual thereafter, reaching a crescendo of about 1300 MW by year 2012, as seen in the graph. In mid 1990’s a renewed enthusiasm on small hydro developments was created, solely due to their becoming economically viable in the face of cost of conventional non-renewable power generation. By 2017, 342 MW of such small hydro power plants contributed average 1000 GWh/annum to the grid.

The potential for major hydroelectric capacity additions in Sri Lanka would virtually cease after development of Broadlands (40 MW) and Uma Oya (120 MW) projects, which are now under construction.

Managing hydropower

Sri Lanka, being a tropical island nation, is primarily dependent upon rain for all its needs of water. In that context, there are competing uses forthat water. Obviously, many of those, such as drinking water and irrigation must have priority over generation of electricity.

These uses will have to be coordinated efficiently, and there is a governmental mechanism available for weekly allocations water for such competing uses.

There had been many instances of compromising hydropower storage to make available drinking water from Ambatale. In addition, about 75 percent of the installed major hydropower capacity of 1384 MW is coupled with irrigation schemes and irrigation will always have priority of water use. Inginiyagala and Udawalawe power plants are exclusively operated for irrigation requirements.

Under such constraints, the power system will be required to manage its allocation of water efficiently, optimizing costs with other thermal power generation and storage. As we have seen, water inflows are high during monsoons, and the storage of the reservoirs fed by respective monsoons must be drawn down before the advent of the monsoons to receive the enhanced inflows. At the same time, the storage available during the dry season must also be used assuming the risks of delayed inflows due to delayed monsoons. And, the equation turns about for the wet season, when hydropower generation is to be maximized to avoid spillage from the reservoirs.

Hydropower: Does it come free?

The high costs are mainly due to the cost of civil engineering works, which may have dams, tunnels, underground structures or even public access roads and communication facilities to such remote locations. These considerations are very much in common, even to small-scale hydropower developments. It would not be possible to compare the costs of two hydro power plants solely on energy benefit basis, unless the other benefits to the society and environment are also properly factored into.

What should also be evident from the above is that the total cost of generation during the wet season may be considerably lower than that in the dry season. So ideally, the price of electricity must come down in the wet season and up in the dry season. But such ups and downs are cushioned by the pricing mechanisms so that at least a firm price is maintained throughout a year.

(Bandula Sirimevan Tilakasena is a Chartered Electrical Engineer, graduated from University of Peradeniya in 1978. He is a former Additional General Manger of Ceylon Electricity Board and a current Member of Sri Lanka Energy Managers Association)

27 Dec 2024 19 minute ago

27 Dec 2024 34 minute ago

27 Dec 2024 46 minute ago

27 Dec 2024 50 minute ago

27 Dec 2024 54 minute ago