30 Dec 2019 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

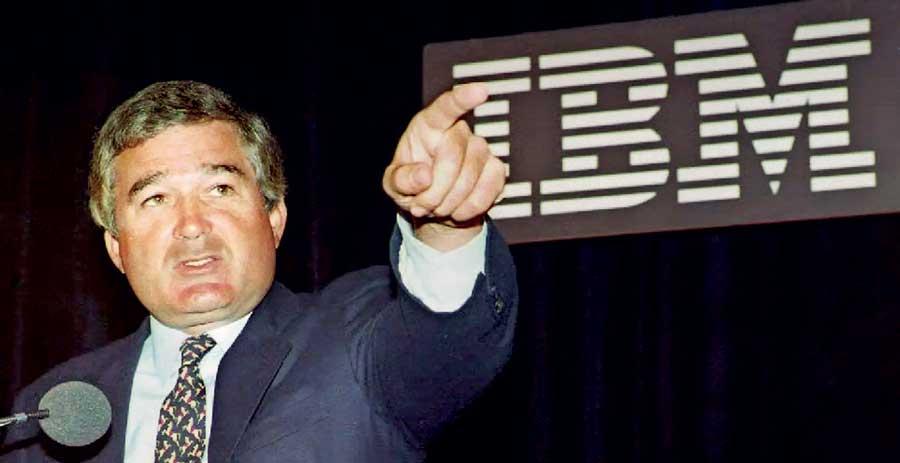

Louis Vincent Gerstner Jr., (born March 1, 1942) is an American businessman, best known for his tenure as Chairman of the board and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of IBM, from April 1993 until 2002. He is largely credited with turning IBM’s fortunes around.

Louis Vincent Gerstner Jr., (born March 1, 1942) is an American businessman, best known for his tenure as Chairman of the board and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of IBM, from April 1993 until 2002. He is largely credited with turning IBM’s fortunes around.

He holds an MBA from the Harvard Business School. Gerstner joined American Express (Amex) in 1978 as Executive Vice President of its charge card division. A year later, he was named President of the Travel-Related Services group, which was responsible for Amex cards, traveller’s cheques and travel-service offices.

At this time, MasterCard and Visa had begun to compete for the company’s market share. Gerstner found new uses and users for the card. In 1980, most department stores did not accept Amex cards – by 1985, the retail sales were second only to airline tickets in card purchases. College students, physicians and women were singled out in various marketing pushes. Corporations were persuaded to adopt the card as a more effective way of tracking business expenses.

Gerstner also created exclusive versions appealing to higher-end clients, such as the Gold Card, which carried an annual fee of US $ 65 and came with a US $ 2,000 line of credit and the Platinum Card, which had a US $ 250 annual fee, a US $ 10,000 check-cashing benefit and private club memberships for travelling executives.

As sales and profits rebounded, Gerstner was promoted to Chairman and CEO of Amex’s Travel-Related Services in 1982 and President of the parent company in 1985. As Chairman and CEO of the Travel-Related Services division, Gerstner spearheaded its successful ‘membership has its privileges’ promotion. Not only was the division continually the most profitable in the company, it led the entire financial services industry.

During Gerstner’s 11-year tenure at Amex, membership had increased from 8.6 million to 30.7 million. He left Amex in 1989 to succeed Ross Johnson as Chairman and CEO of RJR Nabisco

Gerstner was hired as Chairman and CEO of IBM in April 1993 and he was the first IBM CEO who was hired from outside the company. Upon becoming CEO of IBM, Gerstner declared, “The last thing IBM needs right now is a vision,” as he instead focused on execution, decisiveness, simplifying the organisation for speed and breaking the gridlock. Many expected heads to roll, yet Gerstner initially changed only the CFO, HR chief and three key line executives.

In his memoir, he describes his arrival at the company, when an active plan was in place to disaggregate the company. The prevailing wisdom of the time held that IBM’s core mainframe business was headed for obsolescence. The company’s own management was in the process of allowing its various divisions to rebrand and manage themselves - the so-called ‘Baby Blues’.

Then-CEO John Akers decided that the logical and rational solution was to split IBM into autonomous business units (such as processors, storage, software, services, printers) that could compete more effectively with competitors that were more focused and agile and had lower cost structures. Gerstner reversed this plan, realising from his previous experiences at RJR and Amex that there remained a vital need for a broad-based information technology integrator.

He discovered that the biggest problem that all major companies faced in 1993 was integrating all the separate computing technologies that were emerging at the time. He saw that IBM’s unique competitive advantage was its ability to provide integrated solutions for customers – a company that could represent more than piece parts or components. His choice to keep the company together was the defining decision of his tenure, as these gave IBM the capabilities to deliver complete IT solutions to customers.

Services could be sold as an add-on to companies that had already bought IBM computers, while barely profitable pieces of hardware were used to open the door to more profitable deals.

While IBM had been credited with turning the personal computer (PC) into a mainstream product, the company could no longer monopolise its market. A proliferation of cheaper IBM-compatible PC clones that used the same Intel chips and Microsoft operating system software simply undercut it and eroded market share.

Outgoing IBM Chairman and CEO Akers, a company lifer, was excessively immersed in its corporate culture, remaining loyal to traditional ways that masked the real threats. As an outsider, Gerstner had no emotional attachment to long-suffering products IBM had developed to try to regain control of the PC market.

Gerstner wrote that in spite of OS/2’s technical superiority to the dominant Microsoft Windows 3.0, his colleagues were “unwilling or unable to accept” that it was a “resounding defeat” as it “was draining tens of millions of dollars, absorbing huge chunks of senior management’s time and making a mockery of our image”.

By end-1994, IBM ceased new development of OS/2 software. IBM withdrew from the retail desktop PC market entirely, which had become unprofitable due to price pressures in the early 2000s. In 2002, IBM sold the PC division to Lenovo.

Gerstner described the turnaround as difficult and often wrenching for an IBM culture. After he arrived, over 100,000 employees were laid off from a company that had maintained a lifetime employment practice from its inception. In the goal to create one common brand message for all IBM products and services around the world, under Gerstner’s leadership, the company consolidated its many advertising agencies down to one. Layoffs and other tough management measures continued in the first two years of his tenure but the company was saved and business success has continued to grow steadily since then.

From 1993 to Gerstner’s retirement in 2002, IBM’s market capitalisation rose from US $ 29 billion to US $ 168 billion. Despite his success, Gerstner also presided over the company’s decline, relative to newer rivals, as it lost its once dominant position in the IT industry.

Microsoft grew beyond just PC software in the 1990s, hardware companies Apple expanded their market share and entirely new entities such as the Google search engine emerged and created new computer-based business empires.

Following his success in IBM, Gerstner become a mentor to Howard Stringer, CEO of Sony Corporation, tasked with turning around the Japanese corporation. Gerstner established the Gerstner Family Foundation in 1989.

What lessons can we learn from Louis Vincent Gerstner Jr.?

Gerstner believes that principles matter more than processes. For a success of a company, he lists few principles. These principles mainly aimed at focusing on the customer’s needs, on creating value for the company and instil a sense of urgency in the employees’ execution. More importantly, IBM started promoting and rewarding managers and executives who were embracing this new culture, showing other employees that promotions were granted according to new criteria.

Gerstner believes that employees’ perks should be aligned to the whole company’s performance. It maybe through share-based compensation schemes and benchmarked to the competition. This forces employees to understand that the enemy was outside the company – not inside – and to create value for the company.

Gerstner believes that business should organise the units by industry or lines of products and services, it should not be by geographical areas. This helps sharing best practices on a global basis.

Gerstner believes that any business plan should help the company get together, focus on new strategic goals and a defined set of values. He says it always works.

According to Gerstner, any business success is about communication. It’s about honesty. It’s about treating people in the organisation as deserving to know the facts. You don’t try to give them half the story. You don’t try to hide the story. You treat them as – as true equals and you communicate and you communicate and communicate.

(Lionel Wijesiri is a retired company director with over 30 years’ experience in senior business management. Presently he is a freelance journalist and could be contacted on [email protected])

27 Dec 2024 8 minute ago

27 Dec 2024 23 minute ago

27 Dec 2024 35 minute ago

27 Dec 2024 39 minute ago

27 Dec 2024 43 minute ago