10 Apr 2018 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Although Sri Lanka performs well in most health indicators, child nutrition is still a major challenge.

Although Sri Lanka performs well in most health indicators, child nutrition is still a major challenge.

Sri Lanka Human Development Report 2012 revealed that poor nutrition is the chief cause of multidimensional poverty, accounting for 30 percent of the multidimensionally poor (based on 10 indicators representing health, education and living conditions).

Well-nourished people are healthier, better learners and more productive in life. Recognising the importance of improving the nutritional levels, the National Nutritional Policy (NNP) was initiated in 2010.

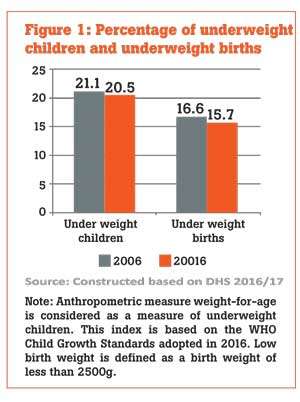

However, the recent nutritional estimates of Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) 2016/17 do not paint a positive picture about the current status of Sri Lanka. Despite the countless initiatives to alleviate malnutrition, child nutritional levels have not improved considerably over the years (Figure 1).

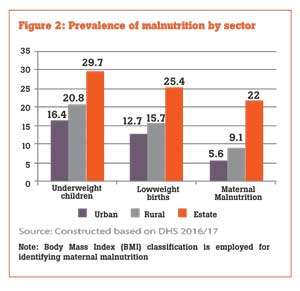

Also, these numbers worsen when it comes to certain population groups, such as the estate sector, where the prevalence of malnutrition is more severe, irrespective of how malnutrition is measured. For example, 30 percent of children under five years of age are underweight while 25 percent babies have low birth weight (Figure 2).

In such deprived regions, there are deep-rooted socio-economic factors, which affect the health and well-being of communities. As revealed in the ‘Socio-Economic Determinants and Inequalities in Child Malnutrition in Sri Lanka’, the socio-economically poor are more likely to be malnourished.

The recent DHS-2016/17 data reveals, a child of the ‘socio-economically poorest’ quintile is twice as likely to be underweight than a child in the socio-economically richest quintile; among the poorest, 27.6 percent of under five-year-olds are underweight, while among the richest, only 12.5 percent of the under five-year-olds are underweight. This means that those who are socio-economically better off, are less likely to be underweight or malnourished.

Further, the IPS research on the ‘Causes of Malnutrition in the Estate Sector’ revealed that the main reasons for child and maternal malnutrition in the estate sector were imbalanced diets – consisting of more starchy and fatty food and not enough high-protein food and high alcohol and tobacco consumption.

Further, it says these factors, coupled with the households’ poor socio-economic conditions and lack of education among women, perpetuate a vicious cycle of malnutrition in the estate sector.

Following the previous research findings and given the higher prevalence of malnutrition in the estate sector, this blog revisits current status of income security, dietary practices and financial management of those belonging to the estate sector.

Socio-economically poor

A main reason for malnourishment in the estate sector is they are socio-economically poorer. Although in the recent years, the poverty levels in the estate sector have reduced nearly fourfold, from 32 percent in 2006/07 to 8.8 percent in 2016/17, this sector is still lagging behind compared to the other parts of Sri Lanka.

As reported in the Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES) 2016/17, 64.6 percent of the estate sector households are among the poorest 40 percent households of the country.

Also, the HIES 2016/17 reveals that the mean monthly per capita income for the estate sector is remarkably low, at around Rs.8,566, when compared to the national average of Rs.16,377. It shows that while the estate sector is just pushing out of poverty, low income may still hinder their food security.

Poor dietary habits

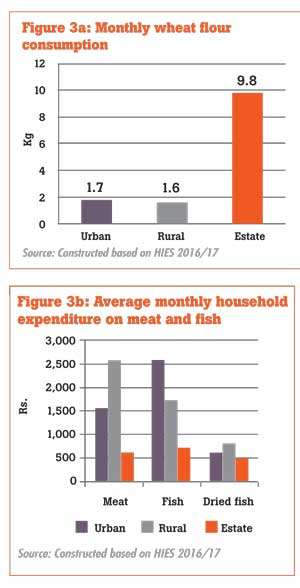

Those in the estate sector continue their cultural dietary practices and consume more wheat flour. The estate sector households’ average wheat flour consumption is steep, at around 10kgs per month, whereas the average household wheat flour consumption is around 1.9kg (Figure 3a).

On the other hand, those in the estate sector consume less animal protein; their expenditure for animal protein is much less when compared to the expenditure patterns of the other regions (Figure 3b). These poor dietary habits negatively affect their nutritional status.

Poor financial management

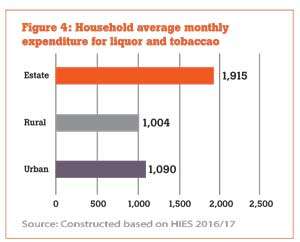

Although the estate sector lags behind economically, the expenditure on alcohol and tobacco in this sector is roughly double, when compared to the average Sri Lankan (Figure 4). The estate sector people are addicted to alcohol due to many reasons, such as being engaged in labour-intensive work, habit and cooler climate.

Also, there are many liquor shops available in close proximity, which also acts as a motivator for people to consume alcohol. The estate sector households’ average monthly expenditure for liquor and tobacco, as a percentage of their monthly food expenditure, is over 11 percent, negatively impacting the households’ food security.

Poor sanitation facilities

The DHS 2016/17 reveals that 57 percent of the estate sector households do not have access to a safe drinking water facility, while 21 percent do not have access to sanitary toilet facility, which negatively affect the health, well-being and nutrition of this group.

How to tackle problem

The NNP has recognized the importance of targeting of nutritional interventions to underserved areas, the plantation community, urban poor and conflict-affected areas. Further, it has identified the necessity to promote behavioural change among the population, enabling them to make the right food choices and care practices.

To be more effective, the policies must recognize and remove the individual causes of malnutrition within the community. For better targeting, it is important to identify food shortages and diversities in diets that exist among the community.

Also, educational programmes on nutrition should be strengthened to focus on the importance of nutritious food – what foods to select, how to prepare and feed children in relation to frequency, density, utilization and the hygienic and nutrition value of food. Such awareness programmes on health and nutrition should also cover complementary feeding and health promotion among children and adolescents.

Further, the NNP has recognised the role of community organisations in programme planning, implementation and monitoring of nutrition intervention programmes. For better targeting, the community must answer the root causes of malnutrition, with the help of trained individuals and develop long-term solutions to the nutrition problem. Formation of women’s groups, with the backing of referral facilities is important to empower women to make the right nutritional choices.

Especially, the community-driven programmes have a major role to play in improving the food security of the deprived estate sector. In addition, the NNP proposes to implement an evidence-based community nutrition package through community workers.

Interventions to increase household food security through better financial management and campaigns against behaviours and practices such as alcoholism should be carried out amongst the youth in estates.

Also, the living conditions in the estate areas should be enhanced by providing better housing and increasing access to safe drinking water, sanitary facilities, drainage and waste management.

(Priyanka Jayawardena is a Research Economist at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). To share your comments with the author, please write to [email protected]. For more articles, visit the IPS blog http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/)

18 Nov 2024 4 hours ago

18 Nov 2024 5 hours ago

18 Nov 2024 5 hours ago

18 Nov 2024 6 hours ago

18 Nov 2024 18 Nov 2024