24 Jan 2019 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The world stands on the brink of a fourth industrial revolution, where dramatic changes in technological advancements will have profound impacts on the future employment landscape and skill requirements. This means that engaging in lifelong learning—be it at school or at work—to anticipate and prepare for future labour market demands is of paramount importance.

The world stands on the brink of a fourth industrial revolution, where dramatic changes in technological advancements will have profound impacts on the future employment landscape and skill requirements. This means that engaging in lifelong learning—be it at school or at work—to anticipate and prepare for future labour market demands is of paramount importance.

In this context, the presence of a large population of youth not in education, employment or training (NEETs) is a major cause for concern. The NEETs consist of both the unemployed—those without work but actively looking for work—and inactive youth outside the labour force, who are not engaged in any educational or training activity. Because they are neither improving their future employability through investment in skills, nor gaining experience through employment, the risks of both labour market and social exclusion is particularly high. Worryingly, Sri Lanka recorded a NEET rate of 26.1 percent in 2016, above the International Labour Organisation global average estimate of 21.8 percent.

An ongoing Institute of Policy Studies study examined the NEET population in Sri Lanka and looked at factors that influence the risks of becoming a NEET, using data from the 2016 Labour Force Survey and descriptive and regression analysis. This article elaborates on some of its key findings.

Disruptions in school-to-work transitions

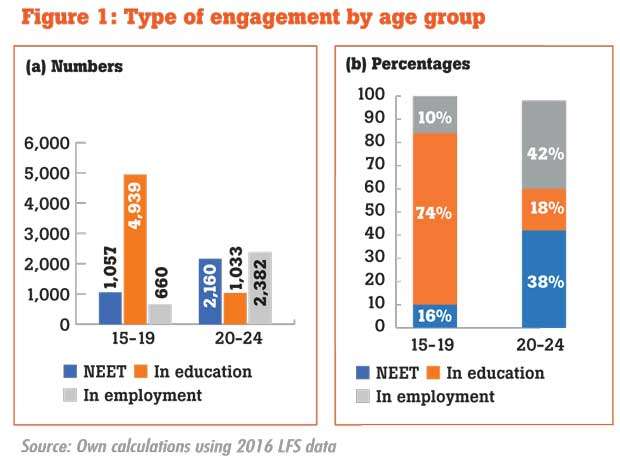

As panels (a) and (b) of Figure 1 show, a breakdown by age indicates that both the number and percentage of NEETs are considerably higher among the older youth group, aged 20-24 years. This observation makes sense, given that a large share of the younger youth cohort (74 percent) is still engaged in secondary education and hence out of the NEET group.

What is concerning is that while 74 percent of the 6,656 15-19-year-olds are engaged in education, less than half of this number or only 42 percent, are employed in the 20-24 age group. This suggests that young Sri Lankans face challenges in making the transition from education to employment, thereby making them more vulnerable to fall into NEET status after completing school education.

School-to-work transitions can be challenging due to multiple factors including lack of required skills, lack of available opportunities or lack of guidance and direction in finding available job opportunities.

Factors affecting NEET status

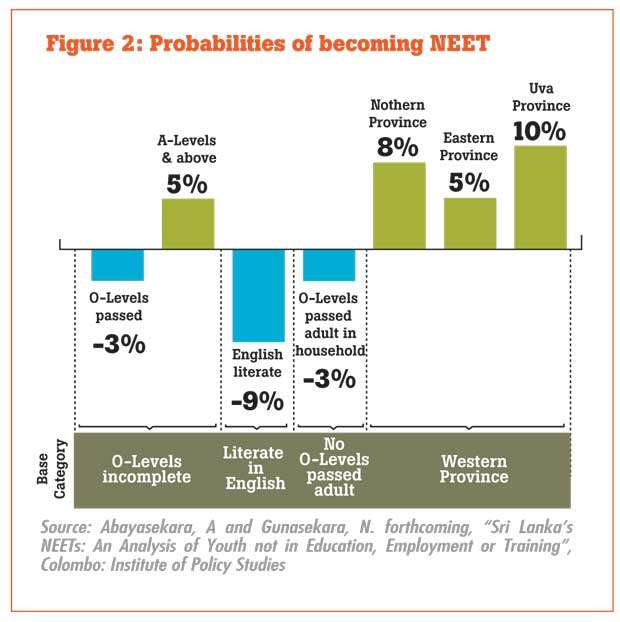

The findings on factors influencing NEET status suggest that the above-mentioned school-to-work transition issues indeed contribute to the large share of disengaged youth in Sri Lanka. As Figure 2 shows, while, not surprisingly, those who have passed the G.C.E. Ordinary Level exam (O-Levels) face a lower risk of becoming NEET compared to the youth who have not completed O-Levels, NEET risks are actually higher for the well-educated youth with G.C.E. Advanced Level (A-Levels) and above qualifications.

This finding is likely reflective of the high unemployment rates observed among Sri Lanka’s educated youth, highlighting issues faced in transitioning from education to employment, despite sound educational qualifications.

An individual who is proficient in English faces a 9 percent lower risk of becoming NEET compared to a similar individual who is illiterate in English, suggesting that soft skills also matter, apart from academic qualifications, to become engaged in education, employment or training. Indeed, prior research identifies soft skill gaps, particularly in English and computer skills, as contributing significantly to the youth unemployment problem.

Living in a household where at least one adult has passed the O-Levels, as opposed to a household with no well-educated adults, also lowers the chances of being NEET. This suggests that parental guidance plays an important role in keeping youth engaged and helping in school-to-work transitions. For instance, a well-educated parent would be more knowledgeable or have the necessary resources and networks, to guide their children towards available educational, training and employment opportunities in line with their capabilities and interests.

Location is another factor affecting the NEET status, with youth from more remote and conflict-affected areas facing higher probabilities of becoming NEET compared to their counterparts residing in the Western Province. Again, transitioning from education to employment is likely to be more challenging in rural settings, given the high concentration of jobs and higher educational and training institutes in urban areas and the relatively less-developed networks and connections in remote locations.

Policy implications

The above findings emphasise the pressing need for policies that would assist in smoothening the school-to-work transition process, so that youth are more actively engaged in the economy.

Finding measures to enhance the employability of educated youth is one priority area. While developing soft skills such as English and information technology are important in making youth more employable – particularly in marginalised areas where access to opportunities are currently limited – also critical is the need to focus on specific skills that future jobs would require. As identified in the 2019 World Development Report, these include advanced cognitive skills such as complex problem-solving, socio-behavioural skills such as teamwork and skills that facilitate adaptability such as reasoning and self-efficacy. Strong human capital foundations are key to building such skills and as such, need to be incorporated into education curricula, starting from early childhood education itself.

There is also a need for government-led career guidance initiatives, established at school level, targeted at advising and directing youth to available education, training, and job opportunities. Such initiatives are particularly important in circumstances where parents are not well-educated and hence not in a position to guide their children themselves and for households living in remote and less-developed locations, with limited knowledge of available education and

employment opportunities.

(Ashani Abayasekara, a Research Officer at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS), can be reached at email [email protected]. To view this article online and to share your comments, visit the IPS Blog ‘Talking Economics’ - http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/)

15 Nov 2024 15 Nov 2024

15 Nov 2024 15 Nov 2024

15 Nov 2024 15 Nov 2024

15 Nov 2024 15 Nov 2024

15 Nov 2024 15 Nov 2024