29 May 2020 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Sri Lanka has emerged as the ‘shining star’ in the efforts to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the global economic recession has started impacting the country at all levels.

Sri Lanka has emerged as the ‘shining star’ in the efforts to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the global economic recession has started impacting the country at all levels.

Globalisation and its much-talked-about benefits have been heavily questioned and challenged. The negatives of heavy reliance on food imports to feed our nation, costing a colossal sum of foreign exchange, have been realised day by day.

Agriculture has become the talk of the town. The president has already given directives to strengthen the production economy and highlighted the priority given to agriculture. The national food production and productivity enhancement drive, which started even before COVID-19, has made a leap jump forward.

Though agriculture is not the only economic sector that contributes to national food security, ‘growing what we can grow best’ and ‘doing what we can do best’ seem the key to success beyond any reasonable doubt. COVID-19 has hit hard on our health and economy. All parties across all sectors have finally teamed up together, start thinking together, to achieve a common goal – to ensure a ‘normal life’ in a ‘new normal’ world. Tackling any challenge of this magnitude is a Herculean task.

To achieve the perceived success during the post-crisis period requires meticulous planning and shared responsibility in putting those plans into action with a focus. We are feeling the pressure to change gears in the economic drive. Sound evidence-based decision-making, while having a holistic view of the agriculture sector, is a must.

The Mahaweli, Agriculture, Irrigation and Rural Development Ministry and its line departments are in the forefront in agricultural operations and let them lead the way. What they require is the unconditional political will and support. The nation should not fall in prey at this crucial juncture to those parties with vested interests, who exploit situations with their whims and fancies, as we have experienced in the agriculture

sector in the past.

The president and the Presidential Secretariat, prime minister and the Finance, Economic and Policy Development Ministry, Plantation Industries and Export Agriculture Ministry, Transport Services Management Ministry, Defence and Tri-Forces Ministry, Central Bank of Sri Lanka, Consumer Affairs Authority, Sri Lanka Police, etc. all have fallen in line, taking many decisions and giving directives to support of the agriculture sector in Sri Lanka, during the pandemic.

University academia (e.g. eight deans of agriculture faculties in universities), professional associations/groups in agriculture, including private sector (e.g. Sri Lanka Institute of Agriculture (SLIA), AGRI.LK – Agripreneurs’ Forum), etc. have offered to be partners in making most prudent decisions to support the economic revival of the country and support the food production drive (productivity enhancement drive) during COVID-19 and in the post-COVID-19 era.

It is not clear whether their proposals and few more submitted by other professional groups in the field of agriculture have been given due consideration by the Government of Sri Lanka (GOSL). As we saw in many newspapers, those recommendations are well articulated, prepared by groups with sound technical knowledge and experience at ground level implementation and warrants urgent attention. In national-level crisis management, the decisions made will change with continuously emerging scenarios. Agriculture is not an exception. We have seen the GOSL changing its original stance, for example, on fixing maximum retails

prices for food products.

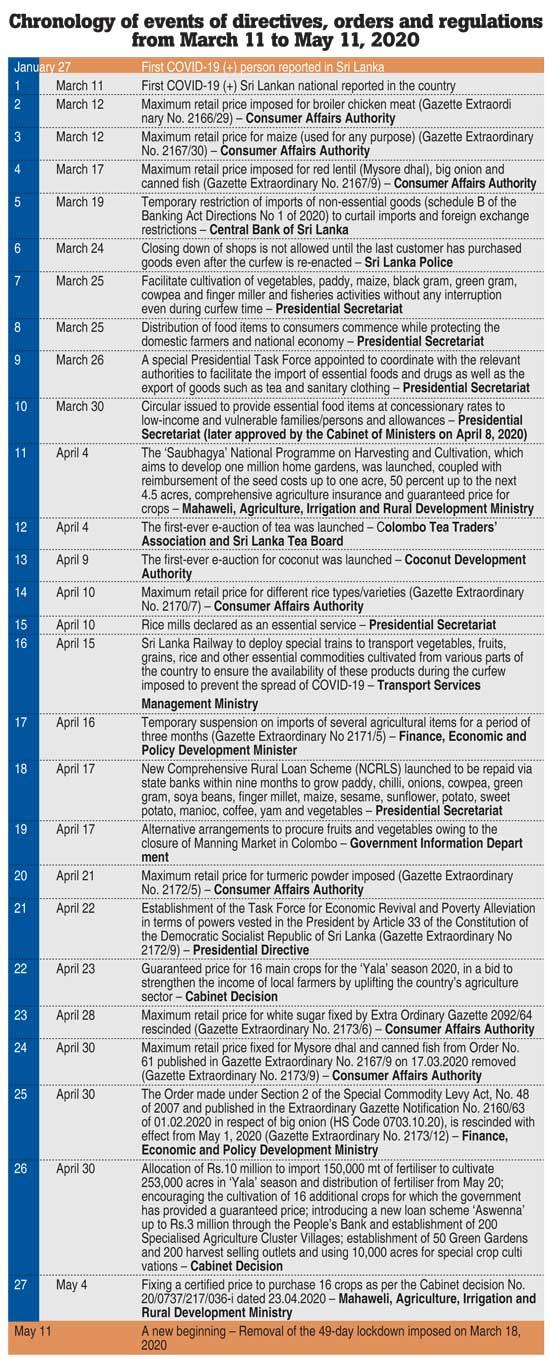

This article briefly looks at some of the key decisions made by the GOSL (see Box) during the 60-day period from March 11, the day of reporting of the first COVID-19 (+) Sri Lankan in the country, to May 11 (official removal of the lockdown), in its efforts to maximise the contribution of agriculture to national food security.

Making food available, accessible and affordable

The Sri Lankan economy is badly hit by the widening global crisis of COVID-19. The country was totally locked down from March 18 to May 10, 2020. Almost all industries were shut, apart from some essential services, such as water, electricity, fuel and food distribution and those producing food (farming) and medical supplies.

Increasing both plant productivity and land productivity are important approaches to enhance the availability of food in Sri Lanka.

Making food available

In 2018, Sri Lanka spent Rs.422.5 billion to import food and beverages (11.8 percent of the total imports). Being a country with the capacity and high potential to produce the requirement of our main food crops and all efforts of the Agriculture Department, we still produce only about 69 percent of maize, 10 percent of big onion, 58 percent of cowpea, 84 percent of ground nut, 49 percent of black gram and 80 percent of red onion, as of 2018.

However, we can be happy with the rice sector. With 3.2 million tonnes of a bumper paddy harvest obtained from the 2019/2020 Maha season recently, before the COVID-19 lockdown and the anticipated harvest of 2.03 million tonnes from the 2020 Yala season, with the new production and productivity drive, there is sufficient rice available in the country for approximately another 16 months (according to the Agriculture Department).

While lots of promise and progress shown in rice production, there is ample opportunity to progress in many of the other food crops, having considered the economies of scale. However, evidence-based decision-making has not taken place once again, for example in determining the

agricultural input requirement.

An enhanced demand for agricultural inputs was obvious with the countrywide home garden development programme (Box – Item 4) and increased cultivation extent in the Yala season. We now hear complaints of unavailability of fertiliser even to be purchased at market prices.

The Cabinet decision taken on April 30 (Box – Item 26) would help but with a significant delay. The ground realities should have been understood better. It is needless to say that the delayed cultivation, due to the non-availability of inputs or due to any other effect and untimely input supply that does not match with the growth stage of the crops, could adversely affect their productivity.

Temporary restrictions imposed on food imports until July 15, 2020 (Box – Item 5) and introduction of a guaranteed price for 16 priority crops identified and agricultural insurance (Box – Items 11, 22, 26 and 27), subsidised inputs (Box – Item 11), allowing farmers to continue cultivating, irrespective of the islandwide curfew (Box – Item 7), etc. no doubt have encouraged the farming community to support this massive food production and productivity enhancement drive. The directive given to work from home had to be redefined to suit the agriculture profession. We have to make sure that the momentum gained is not lost. To make food available, several efforts were made by the GOSL, focusing on the consumers, by fixing the maximum retail price for essential food items (Box – Items 2, 3, 4, 6, 14 and 20) and allowing customers in the queue to purchase items irrespective of the time of imposition of curfew (Box – Item 6).

However, the imposition of the maximum retail price had to be withdrawn, owing to the rapid devaluation of the Sri Lankan rupee (Box – Items 23 and 24).

The appointment of a task force (Box – Items 9 and 21) for economic revival and poverty alleviation is an important move forward to make the country food secure. However, the country urgently requires an agriculture task force to include the director generals of Agriculture, Export Agriculture and Animal Production and Health Departments, directors of the relevant provincial departments, directors of the Tea, Coconut, Rubber and Sugarcane Research Institutes, other relevant state institutions, academia from the agriculture faculties and the private sector, who have been leading the task forces in reality, by implementing agriculture-related actions on the ground with the farming community, including education and awareness creation.

This is a serious drawback in the system as knowing the ground reality is a must in making national-level decisions. Despite these hiccups, the efforts made by the authorities to support farming and also making some important agricultural operations in the supply chain as essential services (Box – Item 15), are commendable.

Making food accessible and affordable

The perennial problems such as failure of having timely availability of the required high-quality inputs, including seed and fertiliser, high-priced technology, due to tariff-related matters, unavailability of skilled labour, ineffective food distribution mechanisms, etc. have overshadowed the efforts of the GOSL during this

crisis situation.

Historically, the inefficiencies in the supply chain have resulted in lower farmer profits and higher consumer prices. These perennial problems are an accumulated outcome of unwise decision-making. Absence of evidence-based decisions when it comes to food importation has become a habit of every government.

Some important decisions have been taken by the GOSL as a solution to support marketing of agricultural produce from the farm-gate (Box – Item 8), reduce food miles by introducing new transport options (Box – Item 16), facilitating introduction of alternate marketing systems (Box – Items 12, 13 and 19) such as online systems, reducing post-harvest losses of perishables, etc.

The e-auctions of tea (first time in 126 years of tea trade) and coconut (first time in 26 years of coconut trade) are landmark events. The ideas that have been floating around for some time (e.g. 20-year dialogue on having e-auctions for tea), have got materialised. One thought ‘mission impossible’ is now a reality.

Though there was a panic buying of tea at the e-auction started on April 4, both tea and coconut auctions would have eased the country’s economic situation to some extent. The sustenance in these and many other improved mechanisms, such as online delivery of food to doorstep introduced during the pandemic, requires strong partnership among the stakeholders, especially through the involvement of the private sector, while ensuring food quality and safety.

The GOSL also needs to focus on making technology affordable to the farmers. This requires revisiting the custom tariff imposed on several imported technologies, including seeds and micro-irrigation systems, to help their adoption by farmers contributing to the overall agricultural economy and food security. Agriculture needs to be modernised by infusing modern technology. Precision agriculture is the need for now

and the future.

(Prof. Buddhi Marambe is a Senior Professor in Crop Science at the Faculty of Agriculture, University of Peradeniya)

25 Dec 2024 2 hours ago

25 Dec 2024 3 hours ago

25 Dec 2024 4 hours ago

25 Dec 2024 4 hours ago

25 Dec 2024 5 hours ago