15 Jan 2021 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The global shock of the COVID-19 pandemic proves, once again, the old adage that ‘it takes a crisis’ and especially so in the world of education. From school leaders to students, educators and parents, are absorbing the lessons, rethinking past assumptions and considering what once seemed like unlikely scenarios.

The global shock of the COVID-19 pandemic proves, once again, the old adage that ‘it takes a crisis’ and especially so in the world of education. From school leaders to students, educators and parents, are absorbing the lessons, rethinking past assumptions and considering what once seemed like unlikely scenarios.

In the pandemic, unfortunately distance learning did not prove to be all that effective for schools. The centralised and overly bureaucratic school systems are vulnerable and ill-equipped to respond to the massive COVID-19 pandemic disruption.

Students, parents and teachers have – in many ways – still not found the right mix to move forward. Sri Lanka will therefore face many challenges to ramp up its education system to staff the economy in the

new normal.

This creates major changes in the demand for knowledge workers and the skills they posses. Emerging countries like Sri Lanka that are building their export bases will need to prepare a large number of people to work in the industry.

However, to maximise the value of the investments, we need to know our current talent gaps, upcoming skill shortages and understand the impact of digital and social media infusion on trade and business. Therefore, the investments we make now in education will contribute significantly to our economic growth post COVID and will be key to our future competitiveness.

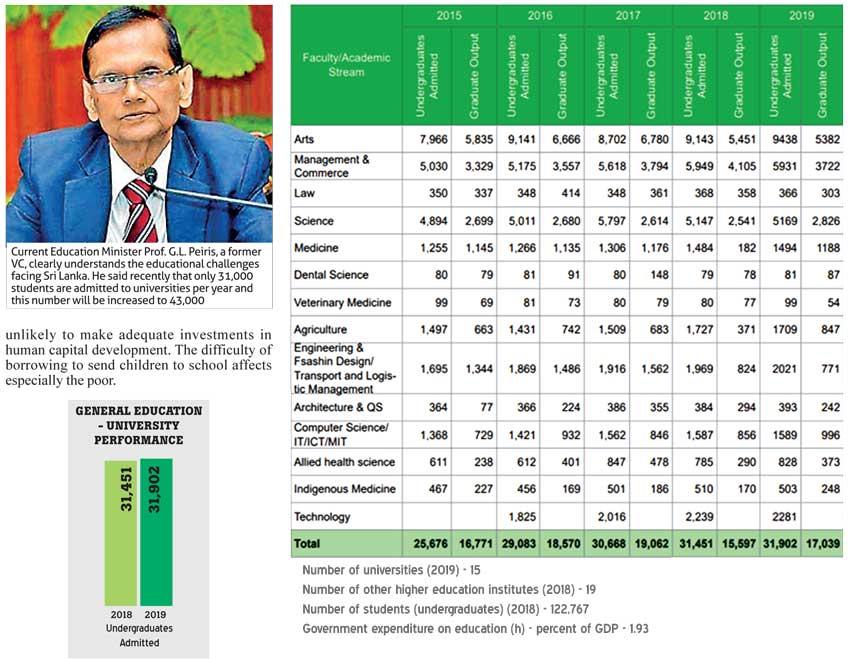

Most households on their own accord are unlikely to make adequate investments in human capital development. The difficulty of borrowing to send children to school affects especially the poor.

Creditors cannot easily stake a future claim on embodied human capital as they can for other types of collateral and therefore many low-income families are forced to invest less in their children’s schooling. These free market failures in principle suggest making concessionary loans available via the state.

A more common alternative is for the government to reduce the direct costs for schooling by making quality public schooling available free or at subsidised rates. Most interventions generally consist of making schooling available free and sometimes even compulsory.

Research suggests the difference between social and economic returns from education is probably higher at primary and secondary levels than at university level. Many positive spillovers come from literacy acquired at lower levels of schooling, while the returns from training at university level are almost fully captured by the higher income of university graduates.

Productivity

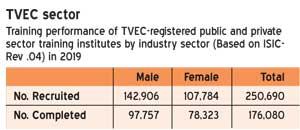

On the other hand, vocational training has high economic payoffs. It improves worker productivity. More importantly, evidence suggests that vocational training is most cost-effective if the trainees have a solid base of primary and secondary education. All of this argues for primary and broad-based secondary education as a means to improve the nation’s productivity and income distribution.

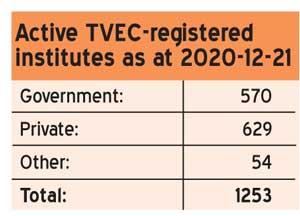

Vocational training in most successful export economies was provided jointly through public and private partnerships (PPPs). This strategy has been successful for countries like Singapore and South Korea to upgrade the skills of their workforce and also has helped the manufacturing-related activities. But while vocational training is widely recognised as important, such training is rarely cost-efficient when provided by the state systems.

Most firms therefore prefer to do their own training, partly because many skills are company specific. There is ample research to show that the return on the training investment is higher in industries that engage well-educated workers and also in environments where there is rapid technological change.

Singapore’s use of training to promote the information technology sector through a structured programme that involved private educational institutions, providing training subsidies to schools and office workers and also by digitising of the civil service, helped the country to achieve leadership in technology-related services.

This success illustrates the importance of the government’s ability to foresee a major opportunity and then promote PPPs to invest in human capital formation.

However, to make it a success, businesses must also stand ready to take advantages of the support the government is willing to provide to promote human capital formation.

In addition, the state should ensure that it maintains the per student share, in real terms, of government funding on education. Given our nation’s economic challenges, PPPs can become far more effective in education delivery than the state doing it on their own in the future.

24 Dec 2024 39 minute ago

24 Dec 2024 1 hours ago

24 Dec 2024 2 hours ago

24 Dec 2024 3 hours ago

24 Dec 2024 4 hours ago