18 Mar 2019 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The government of Sri Lanka has embraced Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) as a key focus of the national trade and development strategy. The rationale of this policy choice has been intenselydebated in the Sri Lankan policy circles. The debate has reached a new height following the release of the report of the Committee of Experts (CoE) appointed by the President to evaluate the Sri Lanka–Singapore free trade agreement. The purpose of this article is to assess this debate

The government of Sri Lanka has embraced Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) as a key focus of the national trade and development strategy. The rationale of this policy choice has been intenselydebated in the Sri Lankan policy circles. The debate has reached a new height following the release of the report of the Committee of Experts (CoE) appointed by the President to evaluate the Sri Lanka–Singapore free trade agreement. The purpose of this article is to assess this debate

The purpose of this article is to contribute to this debate by assessing the trade outcome of Sri Lanka – India free trade agreement (SLIFTA) and Sri Lanka- Pakistan free trade agreement (SLPFTA) and the likely impact of the controversial Sri Lanka–Singapore free trade agreement (SLSFTA). The article focuses solely on the economic rationale of FTAs ignoring political considerations.

Sri Lanka – India Free Trade Agreement (SLIFTA)

The SLIFTA was signed in December 1998 and it became operational in March 2000. The agreement covers only merchandise trade (traded goods). In 2005, Sri Lanka and India initiated negotiations to extend the SLFTA into a Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA), which would cover services and investment in addition to broadening commodity coverage of trade liberalisation.

The SLIFTA adopts a negative list approach to trade liberalisation. To begin with India-Sri Lanka FTA (ISLFTA), India provided Sri Lanka duty concessions (90-100 percent duty exemptions) on 1351 items (at the six-digit level of the Harmonized System). However, tea and garments produced with non-Indian fabrics were subject to import quotas and could enter India only through designated ports.

In early 2003, 2799 more items were added to the concession list, port-of-entry restrictions on tea and garments were relaxed and the quota on garment imports was expanded. Trade preferences granted by Sri Lanka to India are more extensive and larger in proportional terms, but concessions have been granted mostly on products for which MFN tariffs are already very low.

Most of food products exported from India, which have considerable potential for rapid market penetration in Sri Lanka, remain on the negative list with high import duties. The RoOs of the agreement are a combination of RVC and CTS: value added 35 percent of FOB value if the inputs come from both countries or 25 percent if inputs conform one of the two countries.; final product have a different classification compared to intermediate inputs at the 4-digit HS level. The agreement incorporates special and differential treatment provisions to factor in Sri Lanka’s smaller economic size (Kelegama 2014, Weerakoon 2001).

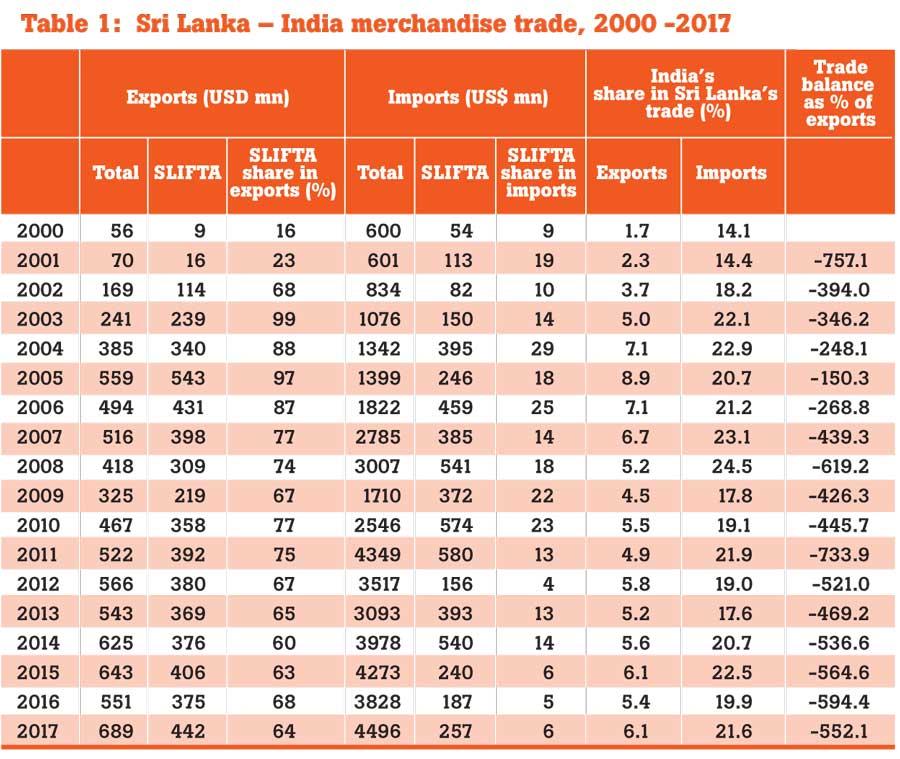

A claim made in various government reports and by proponents of FTA is that Sri Lanka has been a net gainer of the SLIFTA: exports under the agreement account for over 60 percent of total exports to India whereas only a smaller share of import (about 10 percent is covered by the agreement (Central Bank of Sri Lanka 2018, Ratnayake 2017). However, a close look at the data suggests that this is a rather simplistic interpretation of the actual trade outcome under the agreement

(Table 1).

There was a surge of exports from Sri Lanka to India during the first seven to eight years following the agreement came into force. This was mainly due to exports of vanaspati (refined hydrogenated oil, listed under HS 151620) and primary copper (extracted from imported from scrap metal) (HS7403). These products accounted for over nearly 60 percent of total Sri Lankan export to India during this period. However, the expansion of these exports was not driven by Sri Lanka’s comparative advantage in their production compared to India. Rather, it was because Indian manufactures invested heavily in Sri Lanka to produce these products to reap gains from lower Sri Lankan tariffs on required main inputs (crude palm oil for Vanaspati production and scrap metal for extracting primary copper) and preferential (under zero tariff) entry of the end products to India under the FTA (Athukorala 2014).

The export dynamism of vanaspati and copper was short lived, however. Under strong pressure from the Indian Vanaspati Producers Association, India subsequently cut its import tariffs on palm oil from 70 percent in the early 1990s to 7.5 percent in January 2008 andthen to zero in March 2008 and imposed stringent tariff rate quotas on vanaspati imports from Sri Lanka. Consequently,vanaspati exports disappeared from Sri Lanka’s export list from about 2009. In the case of copper, from 2008 India begun to regulate imports from Sri Lanka based on its own domestic value addition estimates made using the London Metal Exchange prices This remarkable policy response was based on India’s concerns about the validity of the RoO certificates issued by the Sri Lankan Department of Commerce. Following the introduction of the stringent procedure for approving market access, a large proportion of Sri Lankan copper exports Lanka because ineligible for entering India under the FTA tariff concessions.

During the ensuing years, Sri Lankan exports to India of some other products were also subjected, from time to time,to various forms of ‘administrative protection’ such as stringent food safety regulations, delaying customs clearance and changes made in the list of ports demarcated for the entry of Sri Lanka goods (Pal 2015). There is also anecdotal evidence that some Sri Lanka exporters have begun to shun the FTA and export under the MFN tariffs because of the cumbersome and costly procedures involved in obtaining RoO certificates and delays in import clearance at the Indian ports.

Reflecting the combined effect of all these factors, the share of Sri Lanka’s exports to India covered by the SLIFTA declined from a peak of 97 percent in 2005 to about 64 percent during the past five years. The share of total exports to India declined from about 8.5 percent in the early 2000s to 6.4 percent during 2015-17.

Even these figures need to be treated with caution because of some cases of alleged ‘trade deflection’ (that is, rerouting some products) of some products from other countries to India via Sri Lanka through alleged manipulation of the country of origin certification. Two highly publicised cases are rerouting to India of aricanuts from Indonesia and black pepper from Vietnam.

The food safety regulations and other administrative restrictions imposed by India on imports from Sri Lanka from time to time clearly support the view that, in practice, implementation of a bilateral FTA is highly susceptible to domestic lobby group pressures, particularly when the FTA partner is a large country with greater bargaining power. Presumably, a small country like Sri Lanka has a much better chance of resolving these issues through the multilateral dispute settlement process of the WTO. Involvement of other WTO members is the dispute settlement process could help overcome resistance arising at the bilateral level. An interesting example is the resolution of the Sri Lanka– EU dispute relating to cinnamon exports.

In 2006, some member countries of the EU introduced a de-facto banned on imports of cinnamon from Sri Lanka because of sulphur dioxide (SO2) content. Sri Lankan authorities were able to successfully resolve the dispute by appealing to the WTO under the Sanitary and Phytosanitary (Animal and Plant Health) agreement. The settlement of the issue involved adoption of a new international food safety standard for cinnamon that helped ensuring transference in food safety monitoring in international cinnamon trade.

It is often claimed that, under the SLIFTA, India has become the second largest destination for Sri Lankan exports. However, India accounts for only about 6 percent of Sri Lankan exports compared to the 26 percent share of the largest destination country, the USA. A close look at the commodity composition of exports cast doubt about possibilities for further expansion of exports from Sri Lanka to India.

Most of the agricultural products, which account for the bulk of total exports to India are subject to supply constraints. Sri Lanka’s total (world) exports of some agricultural products (cinnamon, cloves, black pepper) have increased at a much slower rates or even hardly increased, suggesting that increase in exports to India involved diversion of exports from other markets propelled by duty free market access rather than by a net increase in domestic production.

Most of the manufactured goods exported from Sri Lanka under the FTA benefit from high MFN import tariffs in India, and are, therefore, susceptible to further unilateral trade liberalisation in India. Garments, the main manufacturing export of Sri Lanka, account for less than 3 percent of Sri Lankan exports to India. As a labour abundant country, it is unlikely that India is prepared to substantially expose its garment industry to competition from Sri Lanka on a bilateral basis.

The picture is very different on the import side. The share of imposts from India has on average accounted over 20 percent of Sri Lanka’s total merchandise exports during 2000-17, even though. imports under SLIFTA account for a small and declining share in Sri Lanka’s total imports from India, averaging to a mere 6 percent during this period. This pattern is consistent with Sri Lanka’s high trade compatibility (explained below) with India on the import side.

The high compatibility is in fact what we would expect in trade between a small country and a giant trading pattern with a highly diversified production base. Even though, India has a large and diversified production base compared to Sri Lanka and most of the products in Sri Lanka’s import baskets are produced in India at internationally competitive prices. Moreover, Sri Lanka isa low-tariff country in the region with significant number of zero-duty tariff lines.Given the strong trade compatibility and low import tariff, tariff concessions granted under the SLIFTA are not a significant determinant of Sri Lanka’s imports from India. On the export side, the small share of exports to India (6 percent) seems to reflect the low degree of compatibility between commodity composition of Sri Lanka’s exports and that of India’s exports. India has strong cooperative advantage in world trade in most labour- and resource intensive products exported from Sri Lanka.

The term ‘trade compatibility’ refers to the extent to which the trade patterns of a given country match with that of its partner country: whether products exported by a given partner country are the ones mostly imported by the other partner country and the vice versa. The degree of trade compatibility depends on a country’s comparative advantage in international production, which intern depends on the nature of resource endowment and the stage of economic development.

The economic size of the country also matters because larger counties generally tend to have a more diversified product mix. Most of the FTAs listed in the policy debate as ‘success’ cases (such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), Vietnam – US FTAs and FTAs of Australia and New Zealand with China) are between countries with strong trade compatibility on both import and export sides. According to over estimates (using the methodology of Michaely 1996) compatibility commodity composition between Sri Lanka’s imports and India’s exports in world trade is as high as 68 percent, where the comparable figure relating to Sri Lanka’s exports and India’s imports in only 22 percent.

There was a notable decline in Sri Lanka’s bilateral trade deficit with India during about the first five years following the SLIFTA came into effect. This declining trend has disappeared since then. Over the past decade, the bilateral trade deficit amounted to over five times of total exports to India without showing any declining trend.

Given the glaring asymmetry on export and import sides between Sri Lanka and India under the SLIFTA, India has an exorbitant bargaining power in trade negotiation with Sri Lanka. This arguably accounts for India’s ability to control imports from Sri Lanka by resorting to various non-tariff barriers (Pal 2015), notwithstanding its stated commitment to honour special and differential treatment provisions. The experience so far under the SLIFTA, therefore, does not augur well for Sri Lanka to obtain further market access through the ongoing ETCA negotiations.

Si Lanka Pakistan Free Trade Agreement (SLPFTA)

The SLPTFA was signed in July 2002 and it came to effect in June 2005.In terms of the coverage of the concessions (‘positive’) list and the RoOs the agreement is virtually a mirror image of the ISLINDFA (Ahmad 2012).

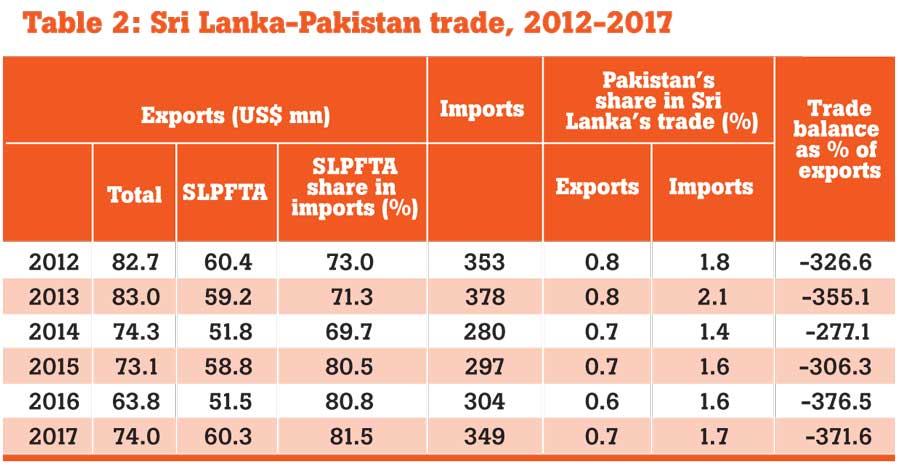

SLPFTA covers about 80 percent of total Sri Lankan exports to Pakistan, but these exports account for a mere 0.7 percent of total Sri Lankan exports (Table 2). The export mix is dominated by agricultural products and ago-based raw material: natural rubber, vegetable products, coconut and some spices.The data for the past five years shows that the average utilisation of TRQs offered under the SLPFTAhas been very low: tea 13 percent; garments 4 percent; betel leaves: 6 percent.

For tea and garments, higher prices of Sri Lankan products compared to imports from other sources are considered a major reason for the low quota utilisation. Sri Lankan garment producers have significantly upgraded their product mix over the past few decades and Pakistan is not attractive market for these products (PBC 2018).

Imports from Pakistan account for about 1.7 percent of total Sri Lankan imports. The product mix consists of woollen fabrics and bed linen, cements, fertilizer, and basmati rice. There is no evidence of a notable increase in imports following the FTA came into effect.

At the time of negotiating the agreement, the Sri Lankan authorities expected that the country’s garment industry would benefit from procuring cotton yarn and fabrics from Pakistan (World Bank 2005). This expectation has not materialised: Pakistani yarn and fabric accounts for a small share (less than 2 percent) of these imposts to Sri Lanka. This was presumably because garment producers must procure high quality inputs from established sources to meet the quality requirements demanded by the international buyers. Moreover, garment producer in Sri Lanka have duty free access to imports from any country under the FTZ scheme and duty rebate provisions available to non-FTZ firms.

Overall, trade patterns under the SLPFTA are consistence with our analytical prior that trade outcome under an FTA depends crucially on the trade compatibility between the partner countries. Of course lack of awareness of among the business community of the trade concessions offered in the agreement, as noted in a recent study by the Pakistan Business Council (PBC 2015), could have played a role at the margin.

Some comments on the Sri Lanka – Singapore Free Trade agreement (SLSFTA)

Unlike the SLIFTA and the SLPFTA, SLSFTA has a wider range of reform provisions going beyond liberalisation of trade in goods to include other areas such as services, movement of professionals, telecommunications and Electronic Commerce. Overall, the subject coverage is similar to the other FTAs involving Singapore. The SLSFTA was signed on 1 Many 2018. However, whether or when and in what form will the agreement come into force remain uncertain following the release in last November 2018 of the report of the Committee of Experts (CoE) appointed by the President to evaluate it.

Singapore is one of the most opened trading nations in the world. Singapore’s average MFN applied duty rate is zero for all imports other than imports of beverages and tobacco for which the averaged rate varies from 1.6 percent to 85 percent (WTO 2018). Thus, the SLSFTA is unlikely to have a direct impact on Sri Lanka’s exports to Singapore.

Some commentators have expressed concern that, under the agreement Sri Lanka would be able to exports to other Southeast Asian countries with which Singapore has entered in to free trade agreement. It simply reflects the popular media practice of treating ‘trade within FTAs’ as ‘free trade’. This view ignores the fact that RoOs, which are an integral part of any FTA, preclude transhipment of goods to a third country though a FTA partner country.

Sri Lanka does not have string trade compatibility with Singapore on the import side (31 percent in terms of the Michaely index). This is because, over the past three decades, Singapore’s export structure has undergone a dramatic transformation. Commodity composition of exports is now dominated by petrochemicals, pharmaceuticals, high-tech parts and components of electronics, and surgical and scientific equipment. Singapore is not a supplier of assembled (final) consumer electronics and electrical foods, automobiles, and low-end parts and comports of these products, which dominate Sri Lanka’s manufacturing imports. Therefore, the market penetration effect in Sri Lanka of Singapore products under the agreement is like to be negligible.

There is a fear that the agreement could open the door for industrial waste and other environmentally harmful products to enter Sri Lanka. This would entirely depend on the implementation of the RoOs of the agreement by the Singapore authorities. Given the well-functioning instructions in Singapore with a proven record of adherence to the rule of law, one can hope that there would be little room for tweaking or lax implementation of the RoOs on Singapore’s part.

The Sri Lankan authorities anticipate that SLSFTA would help linking the Sri Lankan manufacturing sector to global production networks (global manufacturing value chain) (CBSL 2018). How this would happen is not clearly stated in the related government documents. One possibility could be Singapore-based firms operating within production networks relocating some sediments/tasks of the firms in Sri Lanka to exploit advantages from relative production cost differences.

Indeed, this process helped spreading production networks from Singapore to the neighbouring countries during the period from about the mid-1970s to the late 1990s (Athukorala and Kohpaiboon 2014). However, because of the dramatic industrial transformation noted above, industries such as semiconductor and hard disk drive with potential to shift relatively low-end activities to low-cost locations have already disappeared from Singapore.

It is important to note that, the electronics firms currently in operating in Sri Lankan manufacturing export predominantly to countries like Japan, USA, Germany and some European countries. Their exports to Singapore and other ASEAN countries are minuscule, notwithstanding duty free access to these markets under the WTO’s Information Technology Agreement.

Even if there were some opportunities for production relocation, whether the FTA would be an effective vehicle for facilitating the process is highly debatable, for two reasons. First, the very essence of global production sharing within global production networks is locating different segments of the production process globally, rather regionally or bilaterally. The relative cost advantage of producing/assembling a given part or components in the supply chain need not necessarily lie in a country within the jurisdictional boundaries of a specific FTA.

Second, there are formidable complications relating to the application of RoOs for trade within global production networks. Most of the task/segments produced/assembled within production networks have very thing value added margins in each location. In addition, most of imports and export of parts and components trained with production fall under the same HS 4-digit classifications. Therefore, the identification of the origin of trade within production network for granting tariff preferences becomes a major challenge (Athukorala & Kohpaiboon 2011).

Put simply, the rise of global production sharing strengthens the case for multilateral (WTO-based) or unilateral, rather than regional (FTA) approach, to trade liberalisation. To quote Victor Fung, the Honorary Chairman of Li & Fung, the world’s largest supply-chain intermediary based in Hong Kong,

‘Bilateralism distorts flows of goods …. In structuring the supply chain, every country of origin rule and every bilateral deal has to be tackled on as additional considerations, thus constraining companies in optimising production globally’ -Victor Fung, Financial Times, November 3, 2005.

These considerations suggest that more appropriate policy option for facilitating a country’s engagement in global production network is unilateral liberalisation or becoming a signatory to the ITA. Both policy options assure unconditional duty-free access to the required inputs. The case for such broader liberalisation, rather than following the FTA route lies in that global production sharing is a global phenomenon, rather than a regional or bilateral phenomenon.

One of the main envisaged gains to Sri Lanka from the SLSFTA is attracting FDI from Singapore. It is expected that the provisions in the investment chapter (Chapter 10) (safeguards against expropriation, most-favoured nation treatment, repatriation of capital and return from investment) would entice Singapore investors to come to Sri Lanka. However these provisions are exactly similar to those embodied in the Bilateral Investment Protection Treaty (BIPT) between the two countries that has been in force over three decades (since September 1980).

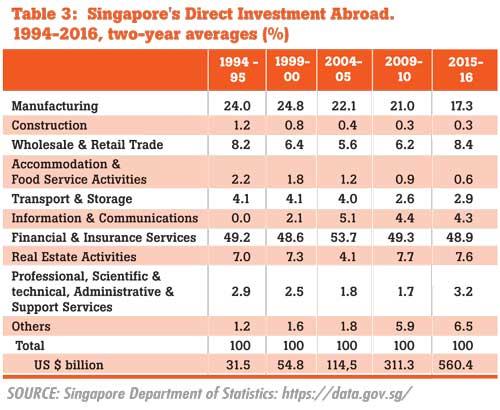

Notwithstanding this long-standing treaty, Sri Lanka has so far been able to attack only a tiny share of rapidly expensing oversees FDI from Singapore. The total stock of our war FDI from Singapore increased from US$32 billion 1994-5 to over 560 billion in 2015-16. However, during this period Singaporean FDI in Sri Lanka amounted to a mere US$ 1.2 billion (based on investment approval records of the Board of Investment). This compassion is much in line with the available multicounty evidence that a BIPT (or an FTA with an FDI chapter, for that matter) is unlikely to entice foreign investors unless they are appropriately embodied in a broader reform addenda to improve the overall investment climate of the country (Hallward-Driemeier 2003).

The data relating to the evolving patterns of outward FDI from Singapore seems to suggest that, even with required broader reforms, opportunities for Sri Lanka to attract Singaporean investors are not very promising. This is because there is limited compatibility between the sectoral composition of Singaporean outward FDI and both Sri Lanka’s development priories and the current stage of economic development. Over a half of outward FDI from Singapore is in the financial sector. These investments are primarily destined to high-income countries.

The manufacturing share of FDI, which is relevant for Sri Lanka’s objective of joining global production networks, accounts for a smaller and declining share of total outward FDI (16 percent in 2015-16, compared to 25 percent in1994-95). MNEs accounts for the lion’s share of Singapore’s manufacturing industry (over 80 percent output). As noted, the SLSFTA is unlikely to be relevant for these MNEs because they make investment location decisions at their headquarters based of a wider inter-country assessment.

Report of the Presidential Committee

A fuller assessment of the report of the Presidential Committee of Experts (CoE) on SLSFTA is beyond the scope of this article. However, we would like to make some brief observations on the report’s key recommendation: ‘Priority need to be given to unilateral trade policy reforms instead of relying on FTAs’.

We fully agree with this recommendation. In fact, we have provided empirical evidence in support of this view, whereas CoE’s recommendation is based on priory reasoning. In addition, we have discussed inherent limitations of the FTA approach to trade opening compared to unilateral and multilateral reforms. We also endorse the recommendation that ‘national trade policy must align with a coherent national development policy framework’. However, we find that the recommendation made by the CoE is not consistent with the objective of addressing supply-side issues to improve the country’s competitiveness in the context of the rapidly changing global economic order. The recommendations are simply ‘old [import-substitution] wine in new bottles’.

The CoE recommends ‘to focus on targeted liberalization so as to avoid interference with the growing or infant industries; infants have to grow at home, they cannot start off as exporters’, following the examples of Japan, South Korea and Brazil during 1965-1985.

We were surprised to see Brazil listed here an example to follow. Brazil is certainly not a development success story (Thomas 2006). Yes, Brazil achieved rapid industrial growth during the import substitution era, but the Brazilian manufacturing industry has miserably failed to maintain this growth spurt during the ensuing decades. In spite of country-specific advantages such as the ample domestic resource base, the vast domestic market and access to markets in neighbouring countries, only a handful of firms emerged during the import-substitution era have continued to reman internationally competitive. Give the lacklustre economic performance in a land of ample unexploded potential, Brazil is known in development policy circles as ‘the eternal land of the future’ (Edwards 2010).

Export-oriented industrialization in Japan and South Korea (and, also Taiwan) was certainly guided and aided by the state. However, their development success was not based on blanket industrial protection as advocated by the CoE (Perkin 2013. Studwell, 2013, Li 1995, Park 1970, Tsai 1997). Trade protection and other government support to firms in these countries were strictly time bound and, more importantly, subject to stringent export performance requirement (export discipline).

Exporting firms always enjoyed duty free status in procuring imported inputs for export production. Culling those firms, which did not measure up, was an integral part of their policy. More importantly, all those countries had strong, committed leadership that was vital for effective implementing these policies. President Park Chun He, who engineered the Korean export-oriented growth miracle, summed up his policy vision as follows:

‘The economic planning or long-range development programme must not be allowed to stifle creativity or spontaneity of private enterprises. We should utilise to the maximum extent the merit usually introduced by the price mechanism of free competition, thus avoiding the possible damages accompanying a monopoly system. There can be and will be no economic planning for the same of planning itself’ (Park 1970, p. 214). (emphasis added).

The CoE has ignored dramatic changes in the global economy in making the recommendations that ‘infants have to grow at home’. This conventional infant industry argument is based on the standard trade theoretical assumption that ‘countries trade in goods produced from beginning to the end within its geographical boundaries’. It is not consistent with global production sharing, which has been the prime mover of export-oriented industrialisation in this era of economic labialisation. To be successful in this form of specialisation, a firm has to have a global focus ‘at birth’. It is important to note that most (if not all) of the successful exporting firms in Sri Lankan manufacturing emerged ‘de novo’ benefitting from the concurrent liberalisation of foreign trade and investment regimes (Athukorala 2019).

We do not agree with the CoE’s recommendation for postponing trade reforms until achieving the required supply side capabilities. Trade liberalisation should instead be an integral part of the overall reform package. It is not possible to achieve supply-side desiderata emphasised in the report such as factor efficiency and productivity growth, improving innovative capacity under a protectionist trade regime.

Contrary to the CoE’s claim, in East Asian countries trade reforms have gone hand in hand with supply-side reforms. By ‘trade liberalisation’ we mean here a move towards a relative more uniform tariff suture that has a low average tariff, with provisions for duty-free access to intermediate inputs for export production, not mindless dismantling of all trade barriers..

Relating to trade policy reforms, the CoE recommends combining para tariff (PT) with customs duties in order to provide protection to domestic manufacturers. The existing cocktail of PTs was introduced in an arbitrary fashion during 2005 – 2015 for revenue raising purposes, not for protecting industries. Thanks to tariff reforms introduced at successive stages during the preceding two decades, by the early 2000s Sri Lanka had been approaching an important policy phase marked by shifting the agenda away from protection and towards achieving a stable and predictable trade

policy regime.

This process was interrupted by the arbitrary introduction PTs and upward adjustment the rates. PTs are an anomaly in the import duty structure that complicates customs administration. There is also evidence that PTs are now a major cause of anti-export bias in the incentive structure. Combining PTs and customs duties would help perpetuating the ant-export bias.

In making the recommendation for combining PTs with customs tariffs, the CoE has overlooked an important feature of the tariff structure: almost all intermediate imports to the country come under zero-duty tariff lines, but these imports are subject to PTs. So, removing PTs would directly help, rather than hinder, domestic producers. Ability to procure intermediate inputs at world-market prices is an important determinant of the competitiveness of manufacturing exports.

Concluding remarks

The role of FTAs in trade performance is vastly exaggerated in the Sri Lankan policy debate.

Most politicians, and much of the media, often do not seem understand the distinction between ‘free trade’ and ‘trade under FTAs’. In reality, FTAs are essentially preferential trade deals and actual trade effect is conditioned by the choice of commodity coverage, which is basically determined by political considerations and lobby group pressure, and rules of origin.

The actual coverage of FTAs in world trade much lower that portrayed in the Sri Lankan debate. Over 80% of world trade is taking place under the standard most favor nation (MFN) tariff system.

The failure to make progress with the process of multilateral liberation under the WTO does not make a valid case for giving priority to FTAs. The proliferation of FTAs over the past three decades has been driven largely by a number of non-economic factors, including the bandwagon effects. If the road to multilateral approach to trade reforms is closed, then the better and time-honored alternative is unilateral liberalization combined with appropriate supply-side reforms.

The outcome of FTAs or unilateral liberalization depends crucially on supply-side reforms needed to improve firms’ capability to reap gains from market opening. However, even with effective supply-side reforms, FTAs would not promote trade in the absence of significant compatibility in trade patterns of the partner countries. Trade compatibility depends on the nature of economic structures and the stage of development of the countries. Location of the countries in the same region (the ‘neighborhood’ factor) does not necessarily ensure trade compatibility. Our estimates of trade compatibility and the analysis of the experience under the SLIFTA and SLPFTA cast doubt on potential trade gains from signing FTAs with countries in the region.

Giving priory to FTA is the national trade and development strategy is not consistent with the government’s objective of linking domestic manufacturing to global production networks (global manufacturing value chain). Global production sharing is a global, not necessarily a regional phenomenon. The relative cost advantage of producing/assembling a given part or components in the supply chain need not necessarily lie in a country within the jurisdictional boundaries of a specific FTA. There is no evidence to support the view that Sri Lanka needs an ‘intermediary’ country (Singapore) to join production networks. The electronics films currently operating in Sri Lankan manufacturing, export predominantly to countries like Japan, USA, Germany and some European countries. Their exports to Singapore and other ASEAN countries minuscule, notwithstanding duty free access to these markets under the WTO’s Information

Technology Agreement.

The available evidence on the role of FTAs in attracting FDI is mixed, at best. The only policy inference one can make from this evidence is that FTAs can play a role at the margin in enticing foreign investors provided the other preconditions on the supply side are met.

Proliferation of FTAs has the adverse side effect of complicating the tariff structure, giving rise to inefficiencies in resource allocation. Overlapping of the standard MFN tariffs with FTA tariff concessions and multiple RoOsattached FTAs weaken efficiency improvements in the custom system, and opens up opportunities for corruption.

(Prof. Prema-Chandra Athukorala is Professor of Economics, Australian National University. Dr.Dayaratna Silva is former Ambassador and Permanent Representative to WTO and former Deputy Head UN-ESCAP New Delhi Office and contribution of Silva to the article does not reflect the organisation that he is currently affiliated with)

15 Nov 2024 1 hours ago

15 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

15 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

15 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

15 Nov 2024 4 hours ago