25 Apr 2022 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Citizens of Sri Lanka started doubting the government’s capability to solve the power crisis, commodity shortages, hyper-inflation and the currency freefall

On April 12, 2022, Sri Lanka declared that it would suspend all external debt payments with immediate effect. Incidentally, Sri Lanka joined the dubious club of global defaulters. This event is similar to a declaration of bankruptcy. It signals the start of a debt restructuring and economic reform phase, with the likely backing of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) (as per April 23, 2022 IMF statement).

On April 12, 2022, Sri Lanka declared that it would suspend all external debt payments with immediate effect. Incidentally, Sri Lanka joined the dubious club of global defaulters. This event is similar to a declaration of bankruptcy. It signals the start of a debt restructuring and economic reform phase, with the likely backing of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) (as per April 23, 2022 IMF statement).

In a series of three articles, we explore this crisis.

Firstly – What accelerated the ‘default’?

Secondly – Containing the damage.

Thirdly – Emerging from the abyss.

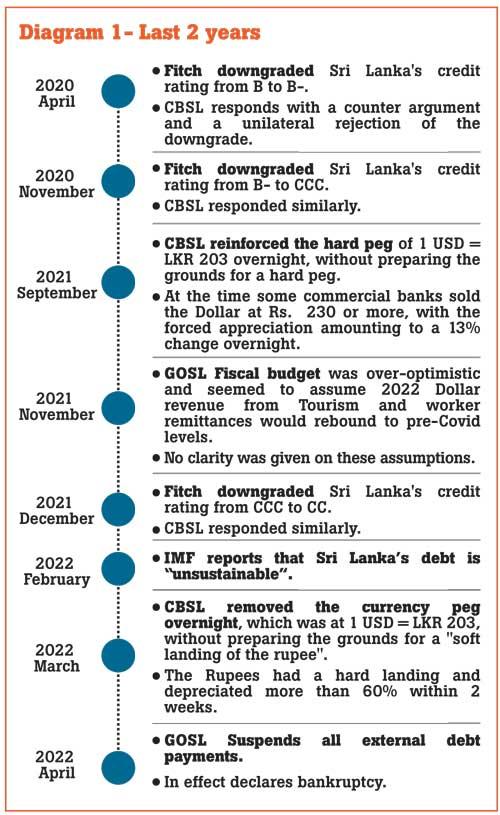

This article, the first in the series, focuses on the causes that accelerated the default. We were already on our way to a default but the events of the last 24 months accelerated our journey towards it. Let’s start with a timeline of relevant events in the 24 months leading up to the April 12 implosion.

Looking at the events in Diagram 1, it’s very clear there was no policy consistency either executed or signalled. In times of a crisis, it can be difficult to differentiate the cause from the effect. The so-called ‘debt crisis’ or the ‘dollar crisis’, which we are facing today, is indeed an effect and is not the cause of the problem. Causes of this crisis are plenty. Yet, there is a primary cause that accelerated Sri Lanka into this abyss in April 2022 – a ‘trust deficit’ that accelerated the effects of the ‘twin deficits’.

Twin deficits are not always problematic

It’s well documented that Sri Lanka has been running a perineal current account deficit (with a minor exception) where our imports exceed the total of exports and inward remittances. Additionally, the Government of Sri Lanka (GOSL) has been running a budget (fiscal) deficit, where the government expenses exceed its income.

But are these twin deficits always problematic? The answer is, ‘it depends on the level and sustainability of the debt’. The said deficits have to be funded by the government drawing down on reserves or else having to continuously borrow both locally and internationally.

However, we know many countries, including some developed nations, run either a single deficit or both deficits. Also, rather than paying-back, they roll-over or refinance most of that debt. Global debt levels have further increased with the COVID outbreak that forced governments to stimulate their economies. The art is to use the ever-increasing debt obligations to achieve more than proportionate growth in sustainable

income (sustainable GDP).

So, why did it become a problem for Sri Lanka?

You can keep borrowing and refinancing until the market believes your debt levels are ‘sustainable’. But the music stops when one or more big lenders or credit rating agencies question your ability to refinance. Alarm bells usually go off when the debt-to-GDP ratio exceeds 90 percent to 100 percent and the credit ratings start trending downwards of BB level (known as mid ‘non-investment grade’). In Sri Lanka, the twin deficits grew to a level that set-off chaos and a ‘trust deficit’ in the system.

What is this trust deficit?

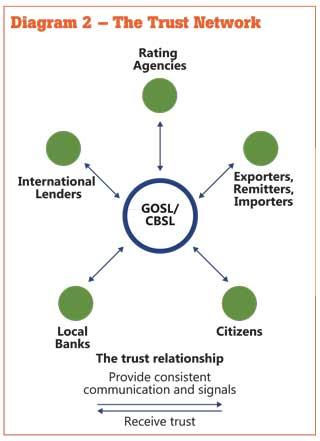

The government and Central Bank of a country constantly communicate with local and international stakeholders providing them with signals of policy direction. In return, the Central Bank and government receive the trust of these stakeholders. However, over the last two years, we saw a breakdown in this communication and the lack of consistent policy signals. A trust deficit refers to a partial or complete breakdown in the trust network. See Diagram 2.

Almost all the stakeholders in this trust network started doubting the communication and signals provided by the Central Bank and GOSL. The following points indicate how this trust deficit manifested in Sri Lanka in recent times.

Almost all the stakeholders in this trust network started doubting the communication and signals provided by the Central Bank and GOSL. The following points indicate how this trust deficit manifested in Sri Lanka in recent times.

Local banks second guessed the nominal interest rates when the ‘real rates’ turned negative, due to roaring inflation. The headline inflation rate is above 20 percent while deposit rates were below 8 percent in March 2022. Even with the 700 basis-point (+7 percent) increase in deposit rates, still the real interest rates are negative. Local banks also doubted the liquidity of the rupee and dollar markets.

Rating agencies lost faith in the transparency, consistency, remedial nature in the policies they expected. The CBSL adopted a combative approach towards rating agencies closing off any hopes of productive engagement.

International capital market lenders lost trust in debt sustainability. For more than a year, the trading yields on International Sovereign Bonds (ISBs) were 30 percent+ for the short-term maturities (debt due in 2022 and 2023), in effect expecting at least a partial default.

Exporters had to book unexpected losses on their dollar proceeds in September 2021, when the exchange rate came down from 230 to 203. Export margins became unviable, as costs escalated while the revenue was capped. The costs were impacted by global supply chain shortages and the inflated price of imported materials funded via the grey-market dollars. They started believing the rupee against the dollar would have to depreciate very soon and started relying on the grey-market.

Importers could not obtain the dollars required even for essential imports. They started relying on the grey-market. The dollar rate was trading at a premium of about 40 percent compared to the formal pegged rate.

Expat workers, who used to remit about US $ 500 million per month, pre-2020, found and resorted to informal channels in the grey-market in order to obtain a higher rate for their dollar remittances.

Citizens of Sri Lanka started doubting the government’s capability to solve the power crisis, commodity shortages, hyper-inflation and the currency freefall.

Where do we stand with IMF?

On the back of this trust deficit, in February 2022, the IMF concluded that Sri Lanka’s debt levels are ‘unsustainable’. With this classification, many rapid financing facilities available with the IMF became inaccessible for Sri Lanka. The most likely programme would be an Extended Fund Facility (EFF), with mutually agreed medium-term structural reforms and a longer repayment period. Till the IMF approves the EFF, the GOSL will have to find bridge financing options.

Path ahead with lenders

In the current context, what happens when we are in default? Looking at what unfolded in recent defaulters Argentina, Lebanon, Greece and Mexico, a possible 10-point path can unfold as follows.

1. Declare bankruptcy – done on April 12, 2022.

2. Define the debt pool affected by bankruptcy – done on April 12, 2022. Amounts to US $ 51 billion of external debt.

3. Establish caretaker government – Remember that the trust is broken and has to be earned back. It cannot be done with the current government and governance structure.

4. Establish a council of technocrats – Use the national list to introduce well respected technocrats into Parliament. Use them as a de-facto council for all major structural reforms and decisions.

5. Maximise bridge financing facilities – Until we enter the IMF programme, the GOSL needs to raise bridge finance, most likely through bilateral government-to-government discussions. While relying on India, China and Japan, we need to diversify the potential lenders to include our main export markets (the West, Middle East) and import partners. This can materialise via extensions of existing loans, new loans and payment-in-kind. Emergency or bridge financing from the IMF is unlikely at this stage since our debt levels are classified as unsustainable (as per February 2022 report of the IMF).

6. Negotiate the debt restructuring programme for remaining foreign loans – The obligations include the ISBs and loans with multilateral agencies. A combination of extensions and haircuts are needed. A haircut is a negotiation with a lender to repay only a portion of an outstanding loan in exchange for forgiveness or a deferred payment on the balance due.

7. Obtain the IMF’s stamp of approval for debt restructuring and medium-term structural reforms.

8. Obtain IMF funding – The most likely programme would be an EFF for three to five years. The loan amount required would be about US $ 3 billion per annum for about three years. This will have to be worked out based on multiple forecast scenarios for exports, remittances, tourism revenue, minus essential imports and negotiated debt servicing payments.

9. Work on improving credit ratings.

10. Gradually regain access to international capital and financial markets.

While we have completed the first two points, we only have a matter of days to execute points three and four to get the ball rolling.

In our next articles, we explore how to contain the impending doom and gloom, while embarking on a path to recovery.

(Jayamin Pelpola has 15+ years of experience in international debt capital markets, investment banking and asset management, including Goldman Sachs (UK) and Nomura USA. He also advised on international debt restructuring and reorganisations efforts for high-yield and distressed entities worldwide. Pelpola received his MBA from Harvard University (Boston, Massachusetts). He also obtained his charters from the CFA Institute (USA) and CIMA (UK). He can be contacted via jayamincp

@gmail.com)

23 Dec 2024 1 hours ago

23 Dec 2024 1 hours ago

23 Dec 2024 1 hours ago

23 Dec 2024 3 hours ago

23 Dec 2024 4 hours ago