03 Jul 2018 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Asian countries have traditionally enjoyed large demographic dividends—i.e. increases in labour supply and savings—that have boosted economic growth. But this decade, the share of working-age population, most notably in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Republic of Korea, has started to shrink, following in Japan’s demographic footsteps.

Asian countries have traditionally enjoyed large demographic dividends—i.e. increases in labour supply and savings—that have boosted economic growth. But this decade, the share of working-age population, most notably in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Republic of Korea, has started to shrink, following in Japan’s demographic footsteps.

Other Asian economies are also expected to face demographic headwinds in the near future.

The shift from a demographic dividend to a dividend tax is occurring much faster in Asia than elsewhere. The working-age population as a share of the total population is already peaking in many countries, reflecting a rapid decline of fertility.

However, many Asian countries are still developing countries. This naturally begs the question: will Asia get old before it gets rich?

If an aging population reduces economic growth, there is a risk that Asia, which has become overwhelmingly middle-income, may fall into a middle-income trap driven by demographic factors. To evaluate this possibility, the recent Asian Development Bank (ADB) working paper Population Aging and the Possibility of a Middle-Income Trap in Asia derives and tests three conditions for a demography-driven middle-income trap.

First, demographic factors should matter for economic growth and convergence. They look at the relationship between the support ratio—or the share of working-age population—and growth rates. This ratio can affect saving and investment and eventually growth.

Second, there should be a negative relationship between the level of development and fertility. As an economy develops, it needs more human capital for learning and adopting more advanced technologies, which leads to higher returns on education and more investment in human capital. This leads to lower fertility due to quantity versus quality trade-off in deciding how many children to have.

Third, fertility should be low enough to lead to a low support ratio. This is more complex than the other conditions because low fertility raises the support ratio in the short term but pulls it down in the long run.

Panel analysis using the Penn World Table 9.0 and World Development Indicators for 178 countries from 1970 through 2014 finds that the first and second conditions are satisfied at 30 ADB developing member countries.

The third condition (that low fertility eventually leads to too few people of working-age in a population—creating an insufficient support ratio for catch-up with advanced economies—is more complicated. Fertility affects the support ratio with a time lag and complex dynamics.

To analyse the condition, we set up a dynamic model to show the relationship between fertility and the steady state support ratio. High support ratios due to low fertility in recent years can correspond to a very low support ratio in the long term.

In other words, if fertility decline raises the support ratio in the short run but lowers it in the long run, the speed of convergence or catch-up with advanced economies will fall, raising the spectre of a middle-income trap.

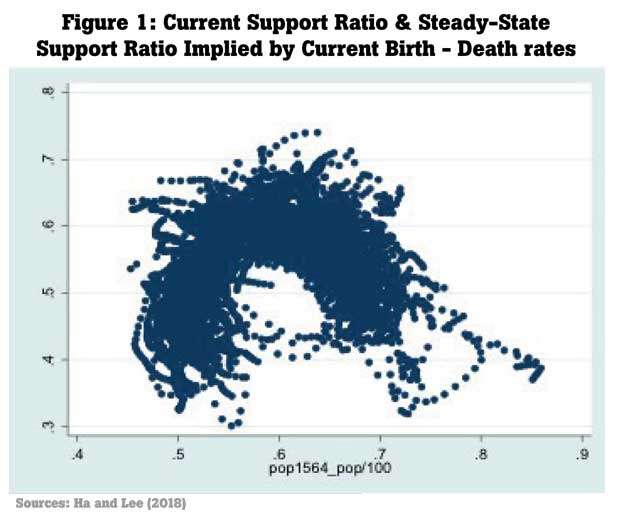

Figure 1 shows the relationship between the actual support ratio (horizontal axis) and the hypothetical steady-state support ratio (vertical axis) to which actual support ratio would converge in the long run if current birth-death rates persist. The two ratios show an inverse U relationship, which suggests that both too low and too high support ratios lead to low support ratios in the long run.

It seems that high support ratios exceeding 0.65 cannot be sustained unless current birth/death rates change drastically. In Asia, many middle-income countries have already reached 0.7 or above.

Furthermore, the support ratio is declining or will soon decline in about two-thirds of countries in Asia.

The main finding is that Asian economies generally meet the conditions for a demography-driven middle-income trap, especially in East and Southeast Asia. Declining support ratios would be a strong headwind for growth, potentially contributing to a middle-income trap.

However, there is no cause for undue pessimism, since a number of policy options are available for Asian policymakers to mitigate this risk.

Above all, policymakers should consider extending the retirement age to expand the working-age population and reduce the number of retirees. If the retirement age is extended to 70 from 65, our model shows that steady-state support ratios increase by 3.45 percentage points in Korea, 4.38 percentage points in the PRC and 4.45 percentage points in Thailand.

In addition, countries should take measures to prevent rapid, sharp declines in fertility and more broadly, maintain fertility at sustainable levels. In this context, the PRC’s recent relaxation of its one-child policy is a promising development.

Finally, measures to reduce the private cost of human capital investment can foster the accumulation of human capital, which mitigates the adverse impact of the slower growth and eventual decline of the workforce. Worsening demographics thus further strengthen the case for human capital investment, which middle-income Asia needs to transition toward more sustainable, productivity-driven economic growth.

(Joonkyung Ha is a Professor at Hanyang University. Sang-Hyop Lee is a Professor of Economics, University of Hawaii at Manoa and Donghyun Park is Principal Economist, Economic Research and Regional Cooperation Department at the Asian Development Bank)

18 Nov 2024 59 minute ago

18 Nov 2024 1 hours ago

18 Nov 2024 1 hours ago

17 Nov 2024 17 Nov 2024

17 Nov 2024 17 Nov 2024