.jpg) The focus of the World Health Organisation (WHO) is on raising taxes on tobacco, in order to raise prices and reduce consumption. This insight explains the serious consistency issues in Sri Lanka on setting taxes and prices on cigarettes.

The focus of the World Health Organisation (WHO) is on raising taxes on tobacco, in order to raise prices and reduce consumption. This insight explains the serious consistency issues in Sri Lanka on setting taxes and prices on cigarettes.

Sri Lankan market context

There are other forms of tobacco consumption in Sri Lanka, such as beedis and betal chewing. There is, as of yet, too little reliable information on the consumption of beedi—studies commissioned by the Ceylon Tobacco Company (CTC) and the Alcohol and Drug Information Centre (ADIC) vary widely. Regardless, it is quite clear that cigarettes remain the most significant vehicle for tobacco consumption in Sri Lanka (the quantity of tobacco in a beedi stick is quite small relative to a cigarette).

CTC has a monopoly in the production and sale of cigarettes in Sri Lanka and the Government of Sri Lanka does not simply regulate the taxes – through section 3 of the Excise (Special Provisions) Act No. 13 of 1989 – but, by convention, also provides direction on the pricing of cigarettes. In fact, by setting taxes in terms of absolute rupee values, rather than as a percentage of price, the government can exercise almost direct control over the pricing of cigarettes.

However, scrutinising the past data exposes a problem: the tax and price setting system for cigarettes in Sri Lanka has a serious flaw – it is ad hoc and in the clutches of political and bureaucratic discretion.

(1)(105).jpg)

The greatest weakness of cigarette pricing and taxation in Sri Lanka can therefore be boiled down to a single word: Discretion.

(1)(105).jpg)

Discretion: Great weakness of cigarette pricing and taxation in Sri Lanka

.jpg) Excise tax on cigarettes has brought about Rs.58 billion in revenue to the government in 2013. This is around 5 percent of government revenue. The cost of manufacturing a cigarette is about Rs.1, while the most sold brand retails at Rs.28. Therefore, small variations in tax rates and pricing affect Rs.10s of billions in government revenue.

Excise tax on cigarettes has brought about Rs.58 billion in revenue to the government in 2013. This is around 5 percent of government revenue. The cost of manufacturing a cigarette is about Rs.1, while the most sold brand retails at Rs.28. Therefore, small variations in tax rates and pricing affect Rs.10s of billions in government revenue.

Yet, none of the financial institutions in Sri Lanka, from the Finance Ministry, to the Treasury to the Central Bank follow a coherent method or formula for the taxation or pricing of cigarettes.

Economic studies teach us that policy or regulatory discretion at the levels of high office can be quite lucrative (for those in that position). High officials who enjoy the privilege of such discretion hence have an incentive to protect it– and very few above them to challenge it.

The greatest weakness of cigarette pricing and taxation in Sri Lanka can therefore be boiled down to a single word: Discretion.

Discretion and its vulnerability to abuse

The application of official discretion on the taxation and pricing of cigarettes, therefore, can be very costly. It can be costly to government coffers and society, when the discretion is abused to reward CTC and can be costly to CTC when the discretion is abused to apply pressure on it. A transparent even-handed policy on taxation and pricing is not open to such abuse.

It is indeed possible that the good traditions of government have ensured that this hugely consequential discretion has always been used responsibly and never for the private or political gain of those who wield it. The point is, however, that the very existence of such discretion certainly makes the system of pricing and taxation of cigarettes in Sri Lanka today vulnerable to abuse.

The analysis that follows shows that there have been times that the discretion has resulted in wide departures from the norm in the taxation and pricing of cigarettes.

Cigarette taxation has been inconsistent

The failure to adjust taxes in some systematic manner can result in large revenue losses to the government and can also put the operations of CTC in jeopardy and uncertainty.

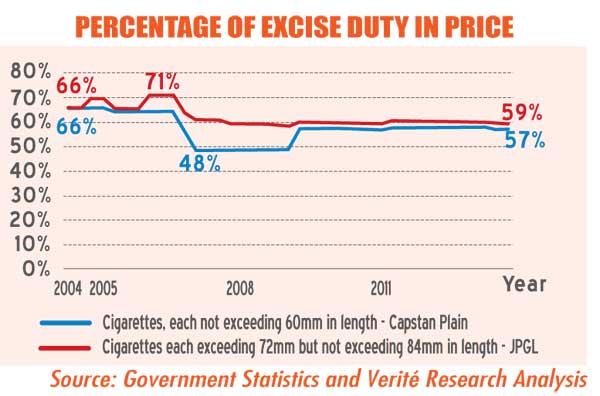

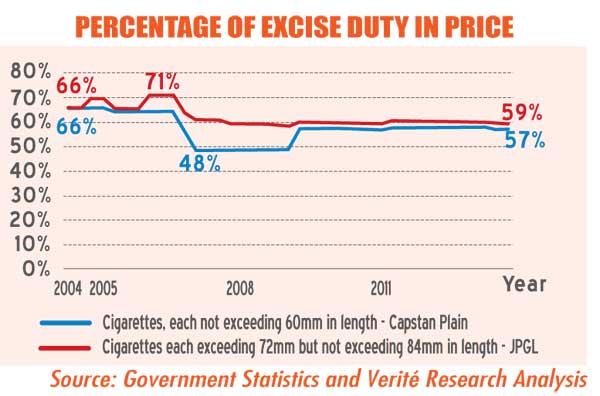

That both of these things have occurred at times can be seen through Exhibit 1. It shows annual variations in the percentage of Excise tax to price since 2004. This is tracked for the two largest selling cigarette brands: John Player Gold Leaf (JPGL), which accounts for 83 percent of the market, and Capstan, which accounts for 11 percent of the market.

The variations in the Excise tax rates post-2004 have generally favoured CTC. For Capstan, they have fallen from 65.6 percent to 57.22 percent. For JPGL’s changes have also mostly favoured CTC dropping from 65.88 percent to 59.32 percent at present (Exhibit 1).

In this period, there is a wide variation in the rates. For Capstan, the high point in taxation was 2004 when it was 65.6 percent. It hit a low point of 48.3 percent for about two years from 2007 (~ 17 percent variation). For JPGL the high point was 70.9 percent in 2006 and the low point was 58.6 percent in 2008 (~ 12 percent variation)(Exhibit 1).

(1)(105).jpg)

The cost of manufacturing a cigarette is about Rs.1, while the most sold brand retails at Rs.28

(1)(105).jpg)

Cigarette pricing has been inconsistent

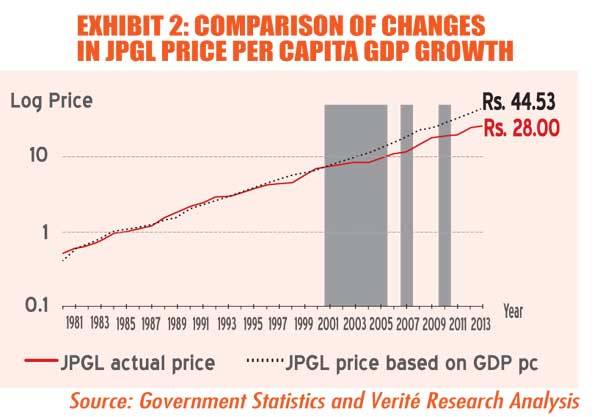

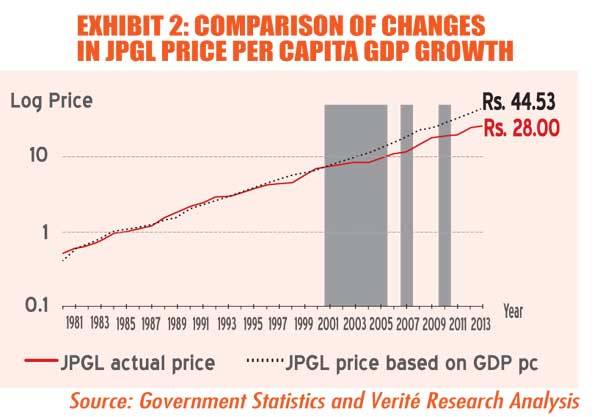

A moderate and systematic method for increasing the pricing of cigarettes would be to see that prices are adjusted every year to keep step with the increase in the per-capita GDP – thereby, mitigating the increase in affordability that comes with the average income growth.

Recent analysis by Verité Research shows that over a long period of time 1981-2000, this has indeed been the case. On average, the price increase of cigarettes in the 20 years from 1981 to 2000 has been the same as the per capita GDP increase during that time.

But the adjustments in those 20 years were not made in an entirely systematic manner. There are significant periods in which the price has been under adjusted and significant periods in which it has been over-adjusted. However, during this period, the deviations from the “correct” adjustment were not large, except in 1997 and 1998 when there was significant under adjustment. But from 2001 onwards, a wide inconsistency arises between the growth of the per capita GDP and the increases in the price of a cigarette (especially in the shaded years in Exhibit 2).

If the overall pricing objective – keeping price increases in line with the growth in the per capita GDP had been followed, then the price of a JPGL by December 2013 would have been Rs.44. However, at present it is Rs.28 – demonstrating the weakness of leaving the decisions to political and bureaucratic discretion, instead of establishing a transparent system.

Time to wake up the parliament

The data presented here shows that there are established fundamentals for a formula on the pricing and taxation of cigarettes and that it can even be squarely justified on the historical averages in Sri Lanka itself.

The responsibility for the proper management of the country’s finances rests finally with the parliament of Sri Lanka. The current exercise of political/bureaucratic discretion has led to disorder and disparities in the pricing and taxation of cigarettes and the discretion remains vulnerable to abuse. A transparent formula adopted by parliament and in keeping with the government policy, can restore fairness, parity and order. All honest stakeholders should prefer this to the current practice. It’s time to wake up parliament.

(1)(105).jpg)

The variations in the Excise tax rates post-2004 have generally favoured CTC

(1)(105).jpg)

(Verite Research provides strategic analysis and advice for governments and the private sector in Asia. Comments welcome, email [email protected])

.jpg) The focus of the World Health Organisation (WHO) is on raising taxes on tobacco, in order to raise prices and reduce consumption. This insight explains the serious consistency issues in Sri Lanka on setting taxes and prices on cigarettes.

The focus of the World Health Organisation (WHO) is on raising taxes on tobacco, in order to raise prices and reduce consumption. This insight explains the serious consistency issues in Sri Lanka on setting taxes and prices on cigarettes.(1)(105).jpg)

(1)(105).jpg)

.jpg) Excise tax on cigarettes has brought about Rs.58 billion in revenue to the government in 2013. This is around 5 percent of government revenue. The cost of manufacturing a cigarette is about Rs.1, while the most sold brand retails at Rs.28. Therefore, small variations in tax rates and pricing affect Rs.10s of billions in government revenue.

Excise tax on cigarettes has brought about Rs.58 billion in revenue to the government in 2013. This is around 5 percent of government revenue. The cost of manufacturing a cigarette is about Rs.1, while the most sold brand retails at Rs.28. Therefore, small variations in tax rates and pricing affect Rs.10s of billions in government revenue.

(1)(105).jpg)

(1)(105).jpg)

(1)(105).jpg)

(1)(105).jpg)