05 Jun 2013 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

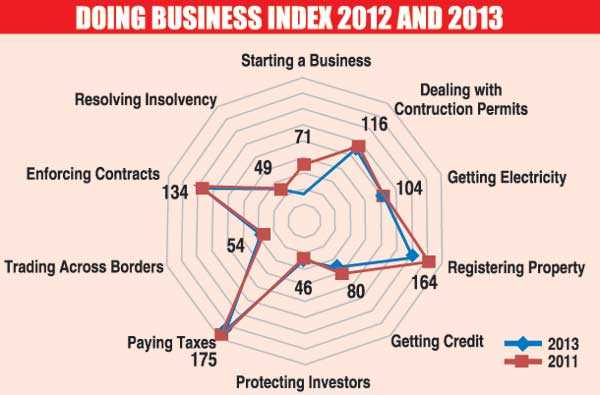

.jpg) Sri Lanka’s rank on the World Bank’s well respected Ease of Doing Business Index (covering 185 economies) improved considerably over the last year. Vaulting from 96th in the world to 81st, an improvement of 15 places, is no mean feat. A back of the envelope calculation based on the World Bank’s ‘Does doing business matter for foreign direct investment?’ report indicates that these reforms should have led to an approximately US $ 1 billion increase in foreign direct investment (FDI). Sri Lanka’s FDI never reached US $ 1.8 billion -it fell over the two-year period from US $ 896 to US $ 813 million. One doesn’t require an economist to tell you this is odd and needs explanation.

Sri Lanka’s rank on the World Bank’s well respected Ease of Doing Business Index (covering 185 economies) improved considerably over the last year. Vaulting from 96th in the world to 81st, an improvement of 15 places, is no mean feat. A back of the envelope calculation based on the World Bank’s ‘Does doing business matter for foreign direct investment?’ report indicates that these reforms should have led to an approximately US $ 1 billion increase in foreign direct investment (FDI). Sri Lanka’s FDI never reached US $ 1.8 billion -it fell over the two-year period from US $ 896 to US $ 813 million. One doesn’t require an economist to tell you this is odd and needs explanation.

26 Nov 2024 3 minute ago

26 Nov 2024 28 minute ago

26 Nov 2024 39 minute ago

26 Nov 2024 1 hours ago

26 Nov 2024 2 hours ago