04 Jul 2014 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

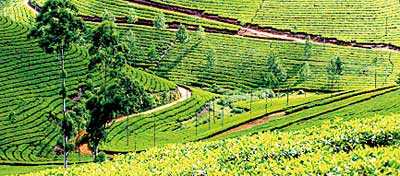

(1).jpg) With world tea consumption expected to reach 3.36 million tonnes by 2021, the industry must address the ethical issues that leave it lagging behind in sustainability. Challenges are many.

With world tea consumption expected to reach 3.36 million tonnes by 2021, the industry must address the ethical issues that leave it lagging behind in sustainability. Challenges are many. Certification bodies have played an important part in getting ethical issues on to the agenda but they have a ‘blind spot’ when it comes to wages in plantations. Sahan said that they need to do more to ensure that workers are paid a living wage rather than simply a minimum wage. Oxfam recently produced a joint report on this with the Ethical Tea Partnership, which represents 29 tea companies.

Certification bodies have played an important part in getting ethical issues on to the agenda but they have a ‘blind spot’ when it comes to wages in plantations. Sahan said that they need to do more to ensure that workers are paid a living wage rather than simply a minimum wage. Oxfam recently produced a joint report on this with the Ethical Tea Partnership, which represents 29 tea companies.

25 Nov 2024 9 minute ago

25 Nov 2024 24 minute ago

25 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 2 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 3 hours ago