21 Jan 2015 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

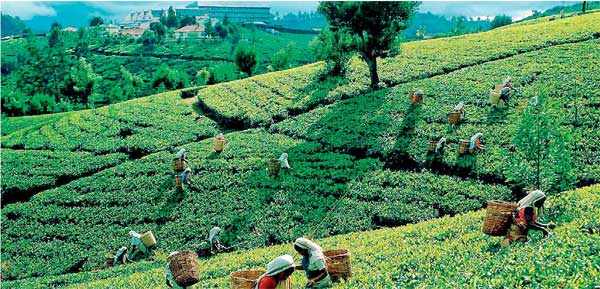

It has been said very recently that the Regional Plantation Companies (RPCs) have renewed t heir call for alternative worker wage model in the face of unsustainable wage increases in the past. They also admit that the future wage increases cannot be stopped.Therefore, let us look at this subject with an open mind and see as to how this works elsewhere. An International Labour Organisation (ILO) study suggests that employee-owned businesses are both successful in business terms and more widely applicable.

It has been said very recently that the Regional Plantation Companies (RPCs) have renewed t heir call for alternative worker wage model in the face of unsustainable wage increases in the past. They also admit that the future wage increases cannot be stopped.Therefore, let us look at this subject with an open mind and see as to how this works elsewhere. An International Labour Organisation (ILO) study suggests that employee-owned businesses are both successful in business terms and more widely applicable.

25 Nov 2024 1 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 3 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 4 hours ago

25 Nov 2024 4 hours ago